Unsurprisingly, protagonists on all sides in the Brexit debate are keen to claim that their views reflect the will of a majority of voters. After all, the decision to leave the EU was made by the public in the first place, so being able to argue that what should happen now is backed by voters is a potentially valuable currency in the political debate. Thus, the Prime Minister, for example, insists that in pursuing Brexit she is delivering ‘the Brexit people voted for‘, a vote that, she argues, should not be questioned by asking voters their view a second time. Opponents of Brexit, in contrast, often take the view that voters were misinformed – even misled – during the EU referendum, and now that they are more aware of the supposed downsides of leaving the EU they should be given the chance to register their second thoughts in a second ballot.

The intensity of this argument reflects, in part at least, the narrowness of the outcome of the referendum in June 2016. Against the backdrop of a 52% vote for Leave and 48% for Remain, not many voters would have to change their minds for the balance of opinion to be tilted in the opposite direction. So, with March 29 – the date when the UK is currently scheduled to leave the EU – rapidly approaching, where does the balance of opinion now lie on the principle of leaving the EU?

Regular users of our site will be aware that polls that have asked people how they would vote in another EU referendum have for some time been pointing to a small lead for Remain. For much of last year our poll of polls, a running average of the last half dozen readings of second referendum vote intentions, put Remain on 52% and Leave 48%, the mirror image of the outcome in 2016. However, given all the potential pitfalls of polling, such a lead was too narrow for anyone to be sure what the outcome would be if a second ballot were to be held.

In recent months, though, the Remain lead has grown somewhat in our poll of polls. By the beginning of October, it had crept up to Remain 53%, Leave 47%. Now, since the turn of the year it has increased further to Remain 54%, Leave 46%. This movement has also been replicated in the pattern of responses to the question that YouGov regularly ask, ‘In hindsight, do you think Britain was right or wrong to vote to leave the EU?’. Until the 2017 general election typically more people said that the decision to leave the EU was right than stated it was wrong. Since then, however, the oppose has been the case. Even so, by the spring of 2018, on average the proportion who said that the decision was wrong (45%) was still only three points higher than the proportion who said it was right (42%). However, in the readings that YouGov has taken in the last three months, that lead has grown on average to as much as eight points, with as many as 48% saying the decision was wrong, and only 40% that it was right.

So, what has happened? Why does it seem that opinion has swung against Brexit, albeit to no more than a modest (indeed, very modest) degree? In particular, does it signal that some Leave voters at least have changed their minds and that the much-anticipated phenomenon (on the Remain side at least) of ‘BreGret’ is finally making an appearance?

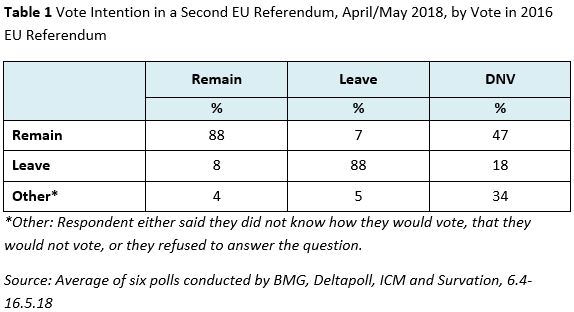

To establish whether or not this is the case, we need to examine the flow of opinion since June 2016. Table 1 provides such an analysis for polls undertaken in the spring of last year. Based on the average of six polls conducted in April/May 2018, it shows separately for those who in 2016 voted Remain and those who backed Leave – together with those who did not vote – how at that point they said they would vote in another EU referendum.

One point immediately stands out. The responses given by Remain and Leave voters were almost an exact mirror image of each other. In both cases, no less than 88% said that they would vote the same way again. And while 7% of those who voted Leave said that they would now vote Remain, they were matched by the 8% of Remain voters who stated that they would now back Leave. In short, at this point movement in and out of the Remain and Leave camps had had more or less no impact on the overall balance of support for the two options. It appeared that if only those who voted in 2016 were to vote again, the outcome would be very much the same as that in the first referendum.

How, then, was it the case that, on average, these polls were putting Remain slightly ahead, by 52% to 48%? The answer lies in the responses given by those who did not vote in 2016. While around one in three of them did not express a preference, among the remaining two-thirds that did, those who said they would now vote Remain outnumbered those who indicated they would back Leave by more than 2.5 to 1. The reason why the balance of opinion had shifted in favour of Remain, even though very few Leave voters had changed their minds, was because those who had not voted before (in some cases because they had been too young to do so) were now decisively in favour of Remain.

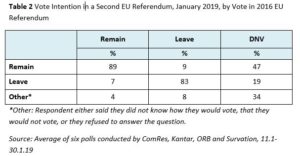

How does this picture compare with the one that is obtained if we undertake the same analysis for the most recent polls that have asked people how they would vote a second time around? Where things stand now is shown in Table 2.

This table suggests that very little has changed among those who did not vote in 2016. The figures for this group of voters are almost identical to those in Table 1, again with Remain preferred to Leave by more than 2.5:1. Much the same is true of those who voted Remain. At 89% the proportion who say that they would vote the same way again is almost identical to the 88% figure in Table 1.

However, among Leave supporters the figures are now a little different. True, by far and away their most common response is still to say they would vote the same way again. But, at 83%, the proportion who would do so is five points lower than it was in the spring of 2018, and six points lower than the current equivalent figure among Remain voters.

It looks then as though the modest but perceptible increase in the lead of Remain over Leave in the last nine months has been occasioned by a small rise in the proportion of Leave voters who now have doubts or, in some cases, second thoughts about their original choice. A not dissimilar pattern is found in the responses to YouGov’s ‘In hindsight’ question. On average, just 82% of Leave voters now say that the decision to Leave was right, down three points on the equivalent figure for April/May last year, while, at 89%, the proportion of Remain supporters who say that it was wrong is much the same as the 88% who did so last spring.

Of course, this analysis but begs another question – why do some Leave voters appear to have changed their minds in recent months? That, of course, is a much more difficult question to answer, not least because the data needed to analyse the various possibilities systematically are not available. However, we can start from the observation that the single best predictor of how people voted in the EU referendum was whether they thought leaving the EU would be good or bad for Britain’s economy, and the fact that, subsequently, we have shown that such economic perceptions appear to be a relatively good predictor of whether or not people have changed their minds about Brexit.

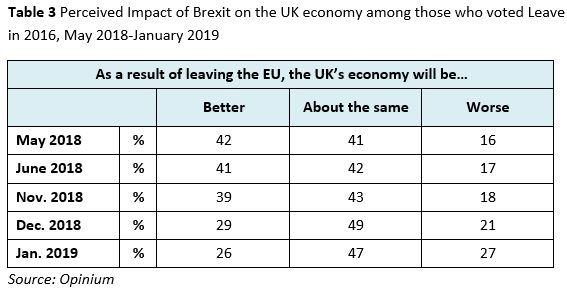

Unfortunately, and rather surprisingly, polling of voters’ evaluations of the economic consequences of Brexit has become relatively scarce in recent months. However, among what there is there is some evidence that voters have become somewhat more pessimistic about the economic consequences of Brexit. The longest and most regular time series on this subject comes from ORB. Since July 2018 their monthly polls have consistently found that more people disagree with the statement that ‘Britain will be economically better-off post Brexit’ than agree with it, in contrast to the position prior to that date when the opposite was usually the case. However, what of course matters to us here is whether Leave voters in particular have become more pessimistic about the economic consequences (after all, any increase in pessimism among Remain supporters should simply reinforce their existing views rather than change their minds) and, unfortunately, ORB’s polls do not tell us how their respondents voted in 2016.

But there is another, albeit much more occasional, time series from Opinium which also suggests that there has been an increase in economic pessimism – and where we can look separately at the trend among Leave voters. This is shown in Table 3. This table demonstrates that in May and June last year, those Leave voters who thought that the economy would be better after Brexit clearly outnumbered those who thought it would be worse. Now, however, the two groups appear to be of roughly equal size. It seems not unlikely that this trend has helped diminish the loyalty of some Leave voters to the choice they made in 2016.

Nobody should assert on the basis of the analysis in this blog that it is now clear that the outcome of a second referendum would be different from that of the first. Given the potential difficulties that faces all polling, the Remain lead is both too narrow and too reliant on the views of those who did not vote in June 2016 (who might or might not vote in another ballot) for anything other than caution to be the order of the day. Even if the polls are entirely accurate, such a narrow lead might still be overturned if Leave were to fight the better campaign – as they are widely adjudged to have done in 2016.

That said, it looks though there has been a modest but discernible softening of the Leave vote. As a result, those who wish to question whether Brexit does still represent ‘the will of the people’ do now have rather more evidence with which to back their argument. In the meantime, it might at least be thought somewhat ironic that doubts about Brexit appear to have grown in the minds of some Leave voters just as the scheduled date for the UK’s departure is coming into sight.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

Proud to have voted leave Report

Carl

I sympathise with your frustration, and agree with you that voting twice on the same question would be undemocratic. But I don’t think it is undemocratic, now that we have much more information to ask the people again whether they want what is actually on offer (rather than the guesswork presented during the referendum campaign).

Bear in mind that “no deal” is not the end of the Brexit process, it is merely starting it again. We will still want to trade with the EU, we will want cooperation on security and crime, we will want rights for UK citizens in Europe, we will want guarantees about the standards of food and medicines, we will want an agreement which prevents Ireland returning to civil war. We have all these now, and with a no deal exit we would lose them all at a stroke.

So the day after a no deal exit we have to start negotiations with the EU, who would want us to agree to the Withdrawal Agreement they made with Theresa May before they talk about any of the rest. But there would be less trust and willingness to cooperate if we leave on bad terms.

No deal would be bad for Britain, and simply puts us back where we were three years ago, starting the talks.Report

I am not a very political person, however, this whole Brexit debacle has got to stop.

I am just a simple man trying to earn an honest living in today’s world..

I cannot see how ANY negotiator can have meaningful negotiations with any form of opposition and hope for a successful outcome when the negotiator has their hands tied before they say a word!

What consequences does the EU face when they know damn well that the UK will be forced in to accepting whatever deal the EU state!

I keep hearing all about how a No Deal Brexit will be so bad for the country, and how good it will be if we Leave without a deal, what deal? what are the specifics, tell us, the general public, how either outcome will affect us. Then put it to the people again, once it has been made clear what the pros and cons of both outcomes will be. (Even though I am against a second vote, as it does not seem very democratic to have one vote, not like the result and then decide on having another one!)

When I originally voted to remain or leave, I did not see on my ballot paper, leave (as long as we get a deal!) I believe it was Remain or Leave.

I know that a deal was promised and a no deal was a million to one against happening, but the long and short of it is under the Article 50 papers, it states that unless a deal is done, then no deal is the default option! Which is what the MP’s now dithering about, voted through parliament when Article 50 was put into action.

Not sure if I will bother voting in either a general election or any second referendum as seems to me whats the point? Those entrusted to carry out the wishes of the people just seem to ignore them anyway!

Report

Sir John. You have been carefully pointing out for many months that a key factor is the relative turnout of different subsets of the population. In your BBC piece on 27th May you chose to focus on headline issues rather than relative turnout. I look forward to hearing your analysis of what the EU results suggest about relative turnout. My question from the floor is.. Do the EU election results indicate that the mobilization of remain voters is increasing (EG relative to at the referendum in 2016)?Report

How are the EU behaving? “The EU” is as much us as any of the 28 member states. They have simply insisted on the rules which we all agreed as member states. We were parties to those rules, and when the negotiations began we agreed the procedure. Report

Hoping that the Leave voters “stay away” from a second referendum is hardly democratic. Having seen how the EU is behaving towards the result of a democratic vote in one of its member states makes me question why I voted remain. Report

I regret that this post is rather long, but I think we need to take a step back and examine what the EU should have been, compare that model to what the EU really is, then analyse the difference and look at what could be done about it.

What the EU should have been

The EU should have been an organisation working to eliminate the possibility of another World War, or at least a European War, and promoting harmony and peace in mankind. In 1975, believing this could be achieved through free trade, I voted to stay in what was then called the Common Market. Many others took the same view.

What the EU really is

I then went to sleep about the matter for over a decade. Then, growing concerned about Lord Denning’s “incoming tide” of EU legislation, I read the Treaty of Rome, which I and probably most other Brits had neglected to do in 1975. I realised the EU was not and never had been just a Common Market and that its true intention was “ever-closer union”.

I also realised that British political leaders in and before 1975 would have known full well the true nature of the EU, but none of them had admitted it. We were told it was all about trade. Therefore I came to the conclusion that I and the whole country had been lied to, and that the lie was still ongoing – we are still told it is all about trade and the current debate about Brexit is all about trade, with no mention of the EU’s purpose. So, in this country at least, the EU was born and exists in deceit.

Also, I realised that the EU was not democratic. The right to initiate or repeal law rests with European Commissioners, who are not elected by voters and cannot be kicked out by them. It breaks the link between elector and legislator that has been so bitterly fought for in the UK. Think Peterloo, Tolpuddle and the suffragettes, for example. Think of Keir Hardie and the formation of the Labour Party. Our EU membership makes their achievements null and void.

Finally, it became apparent to me that the EU sought to replace nation states, not with something better, but by itself becoming a bigger nation state incorporating its members, with all the trappings: a flag, an anthem, a Parliament, a supreme court, a stated intention to create its own armed forces, a wish, and the practice, that its laws should override those of its component parts. Its acquis communautaire is an irreversible ratchet, operating always to transfer more power to the EU. And it is increasingly apparent that it operates in the interests of large multinational companies who can afford to influence it to their benefit.

To summarise, the EU is an undemocratic aspirant super-state to which this country acceded because of a lie. Probably because of these features, the EU is not promoting harmony and peace, but is increasing tensions between nations: the reverse of what it should be doing. Witness Brexit, the bankruptcy of Greece and other southern countries and the problems with Italy, Hungary and Poland. Harsh words are being spoken and old suspicions of French and German rackets being raised. It was not supposed to be like this.

What went wrong?

I believe the intentions of Schumann, Monnet et. al. were honourable. The Coal and Steel Community, and Euratom, sought to bind the sinews of war to obviate another military conflict in Europe. But, to my mind, there were some serious errors, of which I would like to examine three.

The first was the undemocratic nature of the creation, referred to above. There is no direct link between voter and legislator, which goes against the whole tide of history in this country. Had that structural flaw been avoided in the 1950s, the difficulties today would have been different and probably not so serious.

The second was the lie used in 1975 and thereafter by British leaders, also referred to above. Perhaps they thought that, because the EU as intended was a “Good Thing”, a lie was justified and people would come to accept it. In the event, the lie has generated much of the opposition to the EU we see in the UK today – people get angry and suspicious when they realise they have been duped.

The third error was that EU development has latterly been too fast by far. We can all think of people who wanted “He built Europe” inscribed upon their tombstones, but they should have been restrained. Churchill admirably remarked that “Jaw, jaw is better than war, war”. Unfortunately, he did not clarify that war, war could be avoided even if potential combatants had to jaw, jaw for a thousand years without doing much else.

The problem here is that many European nation states did take a thousand years to create and they have deep support and sympathy ingrained even into the DNA of their inhabitants. It was unreasonable, even reckless, of Euro-enthusiasts to expect populations meekly to abandon their nation states over the course of a few decades for the sake of an organisation intent on becoming just a bigger nation state. Some of the intelligentsia might go along with it, but they are in a minority and will only prevail if everyone else is supine – perhaps because the latter have been deceived about the real objective.

What is to be done?

If the EU wishes to survive without becoming a repressive state, the errors I have mentioned must be corrected as far as possible.

The first thing the EU should do is apply the brakes; to maintain its state of development where it is now and stop acquiring any more power for the foreseeable future. Forget the facile analogy about falling off a bike if it is not moving forward. Let the EU’s population become naturally familiar and content with what the EU does, over centuries if need be. Then move on again, slowly. And the EU should forget raising its own armed forces. An undemocratic organisation with its own military, which could be used to suppress countries wishing to leave, would be terrifying.

Secondly, the democratic deficit should be removed. How? I do not know – there is institutional resistance to reform. But it cannot be neglected.

To correct the lie told in this country would be to change the past – impossible. The UK population has partly woken up to the lie, which explains the move from 2:1 in favour in 1975 to 52:48 against in 2016. The trend is likely to continue as the EU’s real nature sinks deeper and wider into popular consciousness in the next few years.

For this reason, frustrating Brexit now would be a disastrous error both for this country and for the EU. The UK would become a bomb waiting to explode as the internal pressure grew. Far better would be for the UK to leave the EU and wait for the democratic deficit to be removed. It can always apply to rejoin then if the population wholeheartedly wished. The UK could even use democratic reform as a pre-condition of re-entry.

I am not hopeful. I believe too many of our politicians are not great thinkers and too besotted with short-term trade issues and party one-upmanship to see the dangers. Few of them have ever, to my knowledge, enunciated anything about the long-term future and direction of the EU. So I think they will frustrate Brexit. I just don’t want to be around when the bomb goes off.

Report

Nobody mentioned “no deal” during the referendum campaign. Many of the campaigners – Farage, Hannan – insisted that Brexit could involve the Norway deal, which Brexiters now dismiss as unacceptably “soft”.

“No deal” is not a solution, since we would then simply have to start a new round of negotiations, just with the other side less inclined to trust us. We have to have some arrangement about trade with our biggest customers.

But trade is a small part of our relationship with the EU. Fro example, we also need security cooperation with the EU – in 2016 we used the European Arrest Warrant to get 154 British criminals back from other countries to face trial for crimes committed here. Our police are constantly exchanging information about crimes committed by criminals working across national boundaries. We also need cooperation in medicines, to ensure that what we import is safe, and that our drug companies can export to Europe.Report

We voted to leave the EU and that means No Deal. That is clear. Politicians the global elites and the mainstream media form an unholy trinity determined to kick Brexit into the long grass. Juncker admitted on TV that is what they do when they don’t like a political decision. The EU is a dictatorship and a prison in spite of sound bites from VaradkarReport

Forty plus years ago we joined the EU, I like millions of others lost out and moaned a bucket full in joining .

Along comes a referendum and a chance to get out, along with millions of new voters we won the vote to leave except we now have to have a deal to be part of the EU.

The PM as I see it, she is a Traitor to the people who voted to leave. what did she say time time and time again, Leave means Leave?

The PM even Bribed the politicians in saying accept my offer and I will step down.

We voted to leave without any ties and that’s what she must do to redeem herself.

Report

Who cares anymore! The western liberal elite forces to subjugate brexit were always going to win as they were firmly embedded into the constitution long before brexit was ever dreamt about and probably always will be. The little people never did matter. Voting is just a charade to legitimise polices in western Europe which are going to be enacted whatever party “wins” power.Report

Greenland left without this endless argument so why cant we? Could it be because the EU want our £9billion each year (that is our net contribution ie the difference between what we pay in and what we get out) and if they can’t have that they have made sure that we pay a massive £39 billion (that is over £1000 per working adult) to ensure that their bureaucrats get their pensions! Not only that but does anyone realise that we will still be paying the EU until 2060 (yes, that is true) although it will be a mere £3-500million during the latter years. (Just think what we could do with that money…) And…. how much do you know about the Swiss referendum?

After a referendum result of 50.3%(against joining) to 49.7%, the Swiss government decided to suspend negotiations for EU membership until further notice.

A mere 0.6% margin but unlike our politicians, the Swiss upheld the referendum decision. And, interestingly, that was the same margin in the Welsh referendum enabling Wales to have its own assembly. No one asked for another referendum then. No one said “But we must make concessions for those who voted against having a Welsh Assembly”. Our politicians need to be held to account. especially Labour MPs who seem to have forgotten that they were elected on their promise that we would leave the EU and they voted to leave on March 29th with or without a deal and yet they have done everything possible to thwart Brexit including voting overwhelmingly to take no deal off the table. If your MP got elected on a promise that he or she has not delivered, you should fight to select someone who canReport

The Swiss also ordered that a referendum voted upon just recently was annulled and then run again because the public were given the wrong information. Unlike our lot who KNOW the referendum was fraudulent (May use this in her DEFENCE twice in court) and the supreme court said that if the referendum had not been ADVISORY then they would have annulled the result immediately for all the fraud involved. An investigation by the National Crime Agency is still ongoing and is likely going to lead to more arrests from the Leave campaign. Btw Politicians are there to work for us. That includes doing deals or changing their minds as new evidence surfaces that shows their original decision was

influence by fraudulent practices. ( Just like the referendum ) Report

I have an idea if all these politicians as so he’ll bent on another referendum, and beleive the result will be different ie a win for remain.

Let’s go for it, But if the result is still to leave even by the smallest margin we leave the very next day with no deal.

My belief is and as been from day one, and I voted leave that it would not happen.Report

In the last few days I have spoken to various people who voted remain and who would now vote to leave. The media never seems to acknowledge that this is a possibility. They all say that they now just want to get out so that it will put an end to it all.Report