Unsurprisingly, protagonists on all sides in the Brexit debate are keen to claim that their views reflect the will of a majority of voters. After all, the decision to leave the EU was made by the public in the first place, so being able to argue that what should happen now is backed by voters is a potentially valuable currency in the political debate. Thus, the Prime Minister, for example, insists that in pursuing Brexit she is delivering ‘the Brexit people voted for‘, a vote that, she argues, should not be questioned by asking voters their view a second time. Opponents of Brexit, in contrast, often take the view that voters were misinformed – even misled – during the EU referendum, and now that they are more aware of the supposed downsides of leaving the EU they should be given the chance to register their second thoughts in a second ballot.

The intensity of this argument reflects, in part at least, the narrowness of the outcome of the referendum in June 2016. Against the backdrop of a 52% vote for Leave and 48% for Remain, not many voters would have to change their minds for the balance of opinion to be tilted in the opposite direction. So, with March 29 – the date when the UK is currently scheduled to leave the EU – rapidly approaching, where does the balance of opinion now lie on the principle of leaving the EU?

Regular users of our site will be aware that polls that have asked people how they would vote in another EU referendum have for some time been pointing to a small lead for Remain. For much of last year our poll of polls, a running average of the last half dozen readings of second referendum vote intentions, put Remain on 52% and Leave 48%, the mirror image of the outcome in 2016. However, given all the potential pitfalls of polling, such a lead was too narrow for anyone to be sure what the outcome would be if a second ballot were to be held.

In recent months, though, the Remain lead has grown somewhat in our poll of polls. By the beginning of October, it had crept up to Remain 53%, Leave 47%. Now, since the turn of the year it has increased further to Remain 54%, Leave 46%. This movement has also been replicated in the pattern of responses to the question that YouGov regularly ask, ‘In hindsight, do you think Britain was right or wrong to vote to leave the EU?’. Until the 2017 general election typically more people said that the decision to leave the EU was right than stated it was wrong. Since then, however, the oppose has been the case. Even so, by the spring of 2018, on average the proportion who said that the decision was wrong (45%) was still only three points higher than the proportion who said it was right (42%). However, in the readings that YouGov has taken in the last three months, that lead has grown on average to as much as eight points, with as many as 48% saying the decision was wrong, and only 40% that it was right.

So, what has happened? Why does it seem that opinion has swung against Brexit, albeit to no more than a modest (indeed, very modest) degree? In particular, does it signal that some Leave voters at least have changed their minds and that the much-anticipated phenomenon (on the Remain side at least) of ‘BreGret’ is finally making an appearance?

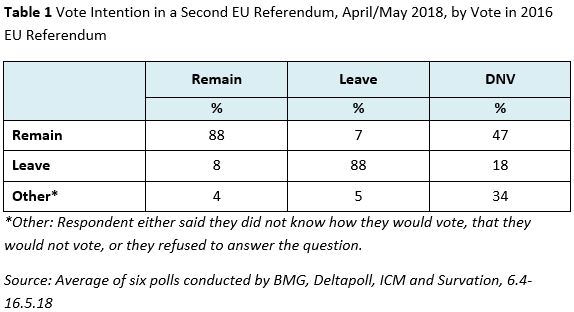

To establish whether or not this is the case, we need to examine the flow of opinion since June 2016. Table 1 provides such an analysis for polls undertaken in the spring of last year. Based on the average of six polls conducted in April/May 2018, it shows separately for those who in 2016 voted Remain and those who backed Leave – together with those who did not vote – how at that point they said they would vote in another EU referendum.

One point immediately stands out. The responses given by Remain and Leave voters were almost an exact mirror image of each other. In both cases, no less than 88% said that they would vote the same way again. And while 7% of those who voted Leave said that they would now vote Remain, they were matched by the 8% of Remain voters who stated that they would now back Leave. In short, at this point movement in and out of the Remain and Leave camps had had more or less no impact on the overall balance of support for the two options. It appeared that if only those who voted in 2016 were to vote again, the outcome would be very much the same as that in the first referendum.

How, then, was it the case that, on average, these polls were putting Remain slightly ahead, by 52% to 48%? The answer lies in the responses given by those who did not vote in 2016. While around one in three of them did not express a preference, among the remaining two-thirds that did, those who said they would now vote Remain outnumbered those who indicated they would back Leave by more than 2.5 to 1. The reason why the balance of opinion had shifted in favour of Remain, even though very few Leave voters had changed their minds, was because those who had not voted before (in some cases because they had been too young to do so) were now decisively in favour of Remain.

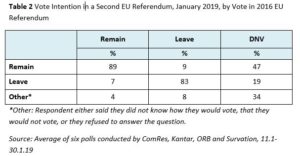

How does this picture compare with the one that is obtained if we undertake the same analysis for the most recent polls that have asked people how they would vote a second time around? Where things stand now is shown in Table 2.

This table suggests that very little has changed among those who did not vote in 2016. The figures for this group of voters are almost identical to those in Table 1, again with Remain preferred to Leave by more than 2.5:1. Much the same is true of those who voted Remain. At 89% the proportion who say that they would vote the same way again is almost identical to the 88% figure in Table 1.

However, among Leave supporters the figures are now a little different. True, by far and away their most common response is still to say they would vote the same way again. But, at 83%, the proportion who would do so is five points lower than it was in the spring of 2018, and six points lower than the current equivalent figure among Remain voters.

It looks then as though the modest but perceptible increase in the lead of Remain over Leave in the last nine months has been occasioned by a small rise in the proportion of Leave voters who now have doubts or, in some cases, second thoughts about their original choice. A not dissimilar pattern is found in the responses to YouGov’s ‘In hindsight’ question. On average, just 82% of Leave voters now say that the decision to Leave was right, down three points on the equivalent figure for April/May last year, while, at 89%, the proportion of Remain supporters who say that it was wrong is much the same as the 88% who did so last spring.

Of course, this analysis but begs another question – why do some Leave voters appear to have changed their minds in recent months? That, of course, is a much more difficult question to answer, not least because the data needed to analyse the various possibilities systematically are not available. However, we can start from the observation that the single best predictor of how people voted in the EU referendum was whether they thought leaving the EU would be good or bad for Britain’s economy, and the fact that, subsequently, we have shown that such economic perceptions appear to be a relatively good predictor of whether or not people have changed their minds about Brexit.

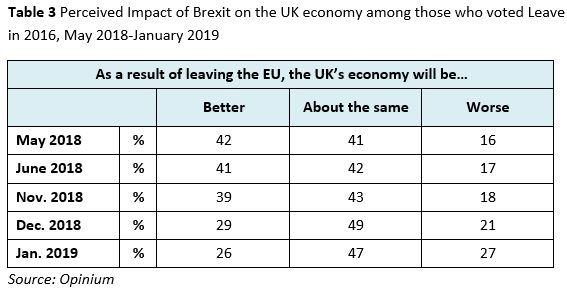

Unfortunately, and rather surprisingly, polling of voters’ evaluations of the economic consequences of Brexit has become relatively scarce in recent months. However, among what there is there is some evidence that voters have become somewhat more pessimistic about the economic consequences of Brexit. The longest and most regular time series on this subject comes from ORB. Since July 2018 their monthly polls have consistently found that more people disagree with the statement that ‘Britain will be economically better-off post Brexit’ than agree with it, in contrast to the position prior to that date when the opposite was usually the case. However, what of course matters to us here is whether Leave voters in particular have become more pessimistic about the economic consequences (after all, any increase in pessimism among Remain supporters should simply reinforce their existing views rather than change their minds) and, unfortunately, ORB’s polls do not tell us how their respondents voted in 2016.

But there is another, albeit much more occasional, time series from Opinium which also suggests that there has been an increase in economic pessimism – and where we can look separately at the trend among Leave voters. This is shown in Table 3. This table demonstrates that in May and June last year, those Leave voters who thought that the economy would be better after Brexit clearly outnumbered those who thought it would be worse. Now, however, the two groups appear to be of roughly equal size. It seems not unlikely that this trend has helped diminish the loyalty of some Leave voters to the choice they made in 2016.

Nobody should assert on the basis of the analysis in this blog that it is now clear that the outcome of a second referendum would be different from that of the first. Given the potential difficulties that faces all polling, the Remain lead is both too narrow and too reliant on the views of those who did not vote in June 2016 (who might or might not vote in another ballot) for anything other than caution to be the order of the day. Even if the polls are entirely accurate, such a narrow lead might still be overturned if Leave were to fight the better campaign – as they are widely adjudged to have done in 2016.

That said, it looks though there has been a modest but discernible softening of the Leave vote. As a result, those who wish to question whether Brexit does still represent ‘the will of the people’ do now have rather more evidence with which to back their argument. In the meantime, it might at least be thought somewhat ironic that doubts about Brexit appear to have grown in the minds of some Leave voters just as the scheduled date for the UK’s departure is coming into sight.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

It’s good to see some of our MPs on TV stating their own views on Brexit away from Party restrictions.l feel this idea they have of listing probable outcomes and then choosing a shortlist will be welcomed. Interesting to see the EU standing up for the people’s Choice..Report

Where and when will we see a comparison of benefits and costs for Leave or Remain? I thought we were to get these before any final decisions will be voted on in Government. How do people feel Now. 350 people marched with Mr Farage. One Million marched to do the opposite.ls there anyone out there who can convince this government that if you give the people who are politically uneducated to make a decision of this Magnitude then having been educated about the subject for three years,who would be surprised if people change their Minds?Report

I see no mention of “shy” voters in this, whereas the’re often mentioned in General Election polls.

Usually right-wing voters are more shy than left voters. (I don’t think Green or LibDem voters are found to be shy either.)

So, is one side of the EU question more shy than the other, or not? I await Prof Curtice’s view.

Report

The EU Commission is not democratically elected and it is them the UK are dealing with, not 27 other countries. Ask the British public if the EU Commission are on our side? Visa versa…Report

Michel Barnier was appointed by the Commission to lead the negotiations on behalf of the Union. He operates within a mandate created by the Council – the elected representatives of the member states, who have to ratify any decisions. Report

Unlike other countries, who submit to second referendums until they get the result their masters want, I hope we British would show some back-bone. I am sixteen years’ old and I don’t want to live in federation under the heels of Brussels and Berlin.Report

Jenni, I am glad that, as a sixteen year old, you are engaging in politics. I believe that all 16-18 year olds should have the vote.

However, I disagree with your point. There is now good evidence that,now that people understand what Brexit might be like, a majority now do not want to go ahead. There have been over 60 opinion polls in the last 18 months, and every one shows a majority for remaining in the EU. If we ask the people whether they want what is now on offer and they vote to leave, then I will accept it, but t would be undemocratic to do something which most experts believe is damaging to the country if the people do not want it.

On your point about “Brussels and Berlin”, we are not under anyone’s heel. The EU is a partnership of member states. All decisions are made by the Parliament (who we elect), and the Council, which is the Ministers (elected) of the member states. When people talk about “Brussels”, they are referring to the Commission, which is the civil service of the Union. The Commission does not make decisions, it can only support the member states and the elected Parliament. As the third largest member, and having English as our native language we have played a leading part in the EU for 40 years. Since 1999, the EU has passed 2500 laws and regulations, our Government has voted for all but 56 of them.

The last 18 months of negotiations have demonstrated how powerful the partnership of member states can be. I think it is better to have these as friends and allies than rivals.Report

Brexit and the Longest Shutdown in US history are affects of the deepest recession since the 1930’s … a recession that some refer to as the third ‘depression’ in the 500 year history of capitalism. Whatever Brexit Paralysis resolves to, the people, particularly those that have to work for a living, will pick up the bill. Cameron couldn’t handle his own Tory right wing and gave us the decision on Brexit. Given the first decision to complete the democratic process we should have the final one. I advocate a single transferable vote on May’s three choices: her deal, no deal and no Brexit … an end to Parliamentary Paralysis! Report

It wasn’t a LEGAL! vote it was a ADVISORY vote ton public reaction. FACT!! This was all planned by the tory government.

All its going to do is make the TORY RICH BOYS!! even richer and the man on street begging to keep there jobs..everything will go up in price by a minimum of 6% on everyday items within weeks of leaving on March..this will be called the New D/DAY will go down in history and that’s is a understatement..remember!! England yous brought it on for the rest of the UK.Report

Sean. I can’t agree with that argument.

Are you saying that the UK is more democratic than other EU countries because UK referenda are one-off affairs, and the public can’t ever change their minds even if perceptions change, as was the case with those held in Germany during the 1930s? In that case, what about the one held in 1975?

How can asking the people to make a decision be “undemocratic”?

The Republic of Ireland held a second referendum on the Lisbon Treaty after the Irish government had gone back and negotiated better terms, then decided to hold a further plebiscite, in which the deal was ratified overwhelmingly on an increased turnout. No EU coercion there at all.

What’s “undemocratic” about that?

Using your logic, there wouldn’t be General Elections every 5 years. MPs, once elected, would stay in office until they passed away or decided to retire. The “will of the people” isn’t set in stone.

You have twice mentioned Kate Hoey. Hardly a good example of a Labour MP. She voted against her own party, and with the Government, ERG, etc. in order to defeat fellow Labour member Yvette Cooper’s motion to block a no-deal Brexit. Perhaps she’s in the wrong party.

I do agree with you that the 2016 referendum should not have been held, but do you really think plebiscites are a good way of deciding national policy? Look at the mess this one has goot us into. Matters such as the Single European Act, and the Maastricht Treaty, were complex issues. Sometimes these things are best left to be debated and scrutinised by our representative Parliament, rather than reduced to a simplistic binary question, and determined by who can come up with the most plausible campaign slogan. Report

Steve: I think the tendency for people to become more conservative as they age is miselading in this case, because there is evidence that the apparent age difference between leavers and remainers is more a matter of education than age per se.

When today’s 70 year olds were 18 only 5% went to HE, now its near 50%, and HE experience correlates strongly with remain voting. This is reflected in the polling figures, with the age threshold between a remain majority and a leave majority moving steadily upwards since the referendum Report

But there won’t be another referendum.

The UK is the first country, in the history of the EU, to have the courage to respect the result of its referendum. Kate Hoey, Labour MP, is right to continually point out the undemocratic nature of the EU, whereby it’s always conspired to overturn the result of any democratic referendum whose result it hasn’t approved off.

Of course, we should never have had the 2016 referendum. Even as early as 1986, the people of the UK should have been offered a referendum of the Single European Act, and then another for Maastricht in the early 90s.

If we had had these referendums, the British people would have had the final say on whether we wanted to transit from a purely economic union to a political one. Margaret Thatcher, but especially John Major and Tony Blair have a lot, oh so much, to answer for. They lead the call for a re-run of the 2016 referendum, but it’s a futile attempt to save their legacies. Report

What is missing from this analysis is the probability that more Leavers than Remainers have died since 2016 and more Remainers than Leavers have reached voting age. Report

Possibly,but you’re not allowing for the natural way in which people generally become more (small c) conservative as they age. Of course, that effect might mean they become more inclined to vote Leave (because of xenophobia), or Remain (because it’s what they grew up with).

(It’s also not a strong argument if you need to wait for people to die just so you can win!)Report

Given that one would have expected opinion to rally behind the result of the referendum (“we’ve had our debate, we’ve voted, it’s settled, let’s get on with it”), the fact that it has moved the other way – to Remain – is all the more striking!

On top of that, the “Leave” option still has around 43-46% when offered as a general idea, but support for it falls off whenever a specific form of Brexit is offered, such as “May’s deal”, “a no-deal Brexit” or a “Norway style Brexit”

Report

Exactly. It’s so much easier to gather support for NOT X than for X. (e.g. to be Anti-Tory than to be Liberal Democrat). There should be a law that if we ever again hold a referendum (on any subject), it must be between nailed-down, concrete, positive options.Report

I get the feeling we are wrong to think in terms of leavers and remainers. My leaver friends are split between no deal and May’s deal. So really we’re divided into three groups. The surprising thing is that my no-deal friends would prefer to remain than be saddled with May’s deal. And my May’s-deal friends would rather remain than crash out with no deal. Doesn’t that make remain the least damaging option? Report

Well, no it wouldn’t, because it would go against the result of the referendum, which would cause enormous social and political damage.

I credit Theresa May with far more political intelligence than a lot of people do. I think she’s never taken her eye off the result of the referendum, 52%-48%. Although she’s ruled out remaining in the Single Market and the Customs Union, I think she’ll compromise and accept staying in the Customs Union, until a trade deal is struck, and I think that Angela Merkel will come to her aid in getting some kind of time limit on this, say five years, which will allow more than adequate time for a technological solution to the border question in Ireland.

She may lose some of the ERG, but she’ll more than make up for that with Labour MPs who’ll support her. Everyone’s mind will become far more focused as 29 March looms, and Theresa May knows it.Report

Whatever the final outcome, there will be enormous social and political damage. 17m voted to leave; 43m didn’t. Of those 17m, a large proportion will be unhappy as it will not be the kind of Brexit they voted for. Report

Well, by the same arithmetic, 15m voted to Remain and 45m didn’t.

Nobody knows what kind of Brexit those 17m voted for. There are many who like to pretend that they know. Anna Soubry said many times “Nobody voted to be worse off”, but how can she possibly know that? How can she possibly pretend to understand the complex psychological nature of 17m people’s political decisions. Taking back sovereignty, the loss of which was signed away by successive governments from the Single European Act (1986) to the Treaty of Lisbon (2007) without a single plebiscite, was an enormously important issue for many voters.Report

Exactly. That’s the trouble with three options (no-deal brexit, May’s brexit and no brexit). Whichever option makes it, the majority will be unhappy. It’s a ridiculous situation to be in.Report

It is unsurprising that economic pessimism has seen a small swing in the Remain / Leave polls on top of the non voters last time adding to the Remain score.

The PM and Government have deliberately pushed a message of Project Fear in terms of no deal in order to get support for her pre-trade agreement deal. This fear based message plus the dislike of her deal itself are bound to sway some voters – it doesn’t make them more or less eurosceptic in the future so I have a sense there will be a kick-back from voters once all this has concluded.Report

There are those that regret voting leave who would like a second chance.

There are those that want to leave whatever the consequences.

There are those who who would still vote remain.

There are those who have since died and those who can now vote.

Although I personally would like a second chance, revoking A50 would be the simplest and cheapest solution, but with May trying to hold a fragmenting Tory party together and Corbyn going against the wishes of Labour I do not hold out much hope for anything but a disastrous No Deal.

What is most worrying is how little people understand what no deal actually means. Report

There is also another large category which gets virtually no attention at all; those who voted Remain in the 2016 Referendum, but who magnanimously accept the result and who want simply to move on.

Those who call for a re-run of the 2016 plebiscite attract a lot of publicity and shout very loudly. They have a very high media profile. They are however, in my opinion, just a small minority of those who voted Remain.

There won’t be a No Deal. Angela Merkel will make sure of that. Report

Angela Merkel has less power than you assume; she can certainly help summon support for an Article 50 extension – if we ask for one – but even that needs unanimous support across 27 leaders.

(Note that the German car industry has stated a preference for No Deal Brexit over any fudge that could damage the integrity of the Single Market.)

In reality, Brexit is not a process which will result in changes to the rules of the Single Market, or the WTO most-favoured-nation rules, both of which make the backstop necessary to keep the Irish border open for goods. (And I’d wager that if that were “resolved” there would still be a number of wreckers in Parliament who’d find other excuses to push for No Deal…)Report

I maintain that Angela Merkel has more power than anyone in the EU. I’m surprised that no journalist has commented on her relative silence on Brexit over the past few weeks or so, particularly over Donald Tusk’s inflammatory comments. I’m sure that she’ll discretely move in towards the end of March and instil common sense all round.

The EU is definitely using the Irish border question to try and keep the UK in a permanent customs union. Kate Hoey, the Labour MP, is one of the few MPs to consistently point out that the amount of trade which goes through the Northern Ireland / Republic of Ireland border is very very small in comparison with the total trade which takes place across all the other EU borders.

Last week on Sky TV I saw Lars Karlsson, an International Customs Expert, speaking from Skurup Sweden. He was talking about the Norway Sweden border. When asked about the infrastructure on the border (we saw truck drivers queueing up in a border office to process papers), he explained it had been put in place years ago, and that these days, it was no longer necessary. He said that the processes that were happening in the office could all take place by modern technology eliminating the need for a physical structure on the border. He said that this couldn’t happen on the Irish border overnight, but that within two years it would be possible. This would mean that the backstop would need to be extended by 3 months, to March 2021, but that’s all. There’s no need whatsoever for a possibly-permanent backstop, and the EU should admit this.Report

Leavers are secretly ashamed.

In a second vote they would vote remain.

2016 leavers voted on a whim.

For some it was a protest vote.

Many young didn’t vote because they didn’t know what EU was. Report

To many of us, the prospect of regaining our sovereignty, making our own laws and forging trade deals across the world had much appeal. What we didn’t appreciate was that leaving would destroy the Good Friday agreement, wreck our relations with the EU, endanger the unity of the UK and make are parliamentary system the laughingstock of the world. I think many of those who voted leave ‘to give the finger to Cameron’ may now vote to remain – if they have any sense. Report

Leavers are secretly ashamed?

Professor Curtice’s findings show that Leavers, in anonymous opinion polls, would almost invariably vote Leave again.Report

The latest polls show No Deal as the single most popular option now which is astounding given the fire and fury unleashed by Remain groups such as Best for Britain for a second referendum. I also think we can all agree that May and the Tories have handled Brexit atrociously yet Leave is still 46%? I find that even more astounding.

Finally riddle me this? The Tories, the party of Brexit, is 7% ahead in the polls yet Remain is gaining ground? There must be some serious cognitive dissonance going on out there. Strip out the YouGov outliers and the UK is basically split 50:50. Report

Link to poll please. I think that’s entirely incorrect.

Report

It appears to be entirely incorrect according to this very site: https://www.whatukthinks.org/eu/questions/if-there-was-a-referendum-tomorrow-with-the-option-of-remaining-in-the-eu-accepting-the-governments-brexit-agreement-or-leaving-the-eu-without-a-deal-which-would-you-support-2-2/?removedReport

How can No Deal be ‘the most popular option’ when Leave as a whole is a minority opinion? Obviously Remain (54%) is the most popular option and leaving the EU is, currently, not a democratic decision. Of course the polls could be wrong but it’s a mistake to pursue this project without testing them.Report

The most important paragraph in the article was the penultimate one, though. Professor Curtice tempers all his previous remarks and concedes that the result of a re-run of the 2016 plebiscite could well be the same. He says nothing however, and it’s not his purpose, of the enormous social division that a re-run would provoke.Report

Sean, some questions:

– Do you think there isn’t already “enormous social division”?

– Do you think that Brexit happening will do anything to heal the division?

– Do you think that voters who were expecting more money for the NHS will be satisfied when all they get is food price inflation and austerity?

The decision is whether to satisfy the 46% (whilst penalising 100% of us economically, to some degree or another), or to satisfy the 54% (whilst potentially undermining the concept of democracy). Hugely risky either way.

I can’t see any way forward that will close Cameron’s version of Pandora’s Box. Most likely, we’ll carry on relatively quietly until some trigger point is reached, and then we will have civil unrest. I take no pleasure in that prediction.Report

Steve, some replies:

Firstly, I’ve been living in France for nearly 30 years, so I can only speak about social division in the UK from what I read and see through the UK media, but my impression is that there was enormous social division during the Referendum campaign and that most people now, even those who voted Remain, just want conclusion, i.e. they just want the government to “get on with it”.

I think that Theresa May takes a very pragmatic view and that most of the public is in line with her on this. She just wants a least-disruptive, most-broadly supported solution to Brexit which respects the result of the referendum, whilst maintaining the closest ties possible with the EU.

Obviously, living in France, I never saw the bus, but I’ve seen pictures of it and the slogans on the side. My take is that the bus never actually promised anything. It just stated a hypothesis based on what we contribute to the EU divided by the number of week in a year (52). It was saying “this is what could be spent on the NHS when we’ve left the EU”. I credit the public with enough judgement to understand that this couldn’t possibly happen while we were continuing to contribute to the EU budget, and that separation, and budget contributions, couldn’t just happen overnight.

I think that what Theresa May wants most of all is to achieve the most pragmatic Brexit possible and I think that she’d even be willing to promise to step down as prime minister once achieved. But I also think that she’d only do so on condition that she’d be given carte blanche over one of the most important social problems within a new government, such as addressing the problem of homelessness and housing.

Report

First, the figure on the bus was a deliberate misrepresentation (not far off double the correct figure), regularly challenged, but never removed. And it was never a real “saving” to be made. We have already lost £30 billion in lost economic growth since the referendum, and firms are moving some or all of their businesses out of the UK.

Are you confident about your rights as a British citizen living in France?

Report

There has been debate about the relative importance of age and education in the original referendum result, but much less about employment status. However, the most recent Daily Express Opinium poll does so, and suggests that this is a neglected factor. It shows that in the original referendum remain led leave by 4 points among employed people, but trailed by 19 points among the 55+ population.

On how people would vote if a new referendum were held today, the results are even starker. Remain leads by 15 points among employed people, while among people aged 55+, the leave lead remains 19 points. A similar pattern in party voting intention, with a Labour lead of 11 points among the employed, and a conservative lead of 24 points among the 55+ population.

One can speculate about the explanation, but might note that those who are currently economically active are closer to the reality of the economy than those who have retired (who form more than half of the inactive population).

Report

A second referendum once the Leave details are clear is fair in light of the fact vs fiction and precedents have been set in other countries as such. Constitutionally the referendum in UK is only advisory, it is parliamentary votes that are binding.

The cohort effect should be recognised in the event that Leave happens with a commitment to hold a referendum X years ahead so that it may be re-assessed in light of whatever the experience turns out to be and in case opinions of the cohort do not change without requiring this to become a function of party politicking or necessitating general elections etcReport

But it wouldn’t be a second referendum, it would be a third (the first one was in 1975).

I would be quite happy with your idea as long as the third referendum takes place in 2057, which would give us an equally long period of “reassessment”. Though I think by 2057 the European Union will have broken up and will have long since been replaced by a New Hanseatic League centred around the North European countries working in harmony with, but not in political unity with some kind of confederation of South European countries, probably led by France.Report

It would be the *first* referendum to ask do you prefer (a) the Withdrawal Agreement or (b) the status quo.Report

Well, that’s as may be, but it begs the question why we were not posed the referendum choice in the 1980s; do you prefer (a) Remaining in an economic union, the EEC or (b) Progressing towards full economic and political union (the EC, which later became the EU)?

Unfortunately we were never offered that existentialist choice. That’s the tragedy which underscores our current predicament.Report

Your article should surely (at least) mention the change in the electorate itself as a result of older people dying and new voters emerging amongst the young!Report

It does mention the new votersReport

The problem with that argument is that existing younger voters continue to age and become older (more conservative?) voters.Report

This all seems flawed to me. What about the change in voter cohort?Report

No question… of do people WANT a ref.. asking them which way they would vote is fine, but ask them if they want one or not

Report

You make a good point Andrew. This analysis only asks hypothetical questions about what people would do if there was a third referendum (the first was in 1975 of course). I’m certain that if the pollsters asked “Do you want another referendum on Brexit?” the answer would be overwhelmingly “No”. That’s the feeling I get from listening, over the past year, to loads of political discussion on Question Time, Any Questions, Pienaar’s Politics, Sky TV etc.Report

If we make bad points together, do we become one?Report

WhatUKthinks does have polling information, apart from this blog article, on this question.

Look for “do-you-think-there-should-be-a-second-referendum-to-accept-or-reject-the-terms-of-britains-exit-from-the-eu-once-they-have-been-agreed” for example.Report

This analysis does not take account of the difference in opinions expressed for a nebulous ‘Leave’ versus a concrete Leave proposition. When people are asked about a specific plan for Leave, there is significantly less support for it, whereas the 2016 Referendum was fought without an understanding of what Brexit meant. In this way, the trade-offs implicit in any model for Brexit were not discussed.Report

… and in that it echoes the referendum question. Any “nuanced” question would have invalidated the base data set, and would have served only to split the leave vote. In or out, remain or leave, it’s binary and very simple.Report

It is my opinion that if there is a second vote a lot of leavers will not vote and more previous non-voters will vote remain. And so the result will be more like 55-45 for remain. But a) I am no expert and b) this could be wishful thinking but c) it could also be true!Report

i voted say, and i would even refuse to take part or vote leave. most people know party politics are at play. and Brexit never had a fair shot.

while i prefer to stay. i do believe there are forces at work against the people, who never wanted brexit. and i know i’m not alone. and next time it could be my vote on the end of itReport

The dark forces were deployed by the Leave side. There needs to be a public inquiry into the complete failure of governance. Report

Table three should state January 2019 not January 2018?Report

I’m not sure it’s enough information to ask for a single answer to the question “As a result of leaving the EU, the UK’s economy will be…” as it totally depends on the nature of the future arrangement. e.g. leaving under a Norway style arrangement there’d be much less economic damage that leaving with no deal. Report