On May 6, the parties face their first significant electoral test since the December 2019 general election. As well as devolved elections in Scotland and Wales (and a parliamentary by-election in Hartlepool), in England there will be a double round of local elections as the contests that were postponed last year because of the pandemic are held alongside those that were scheduled to happen this year anyway. Nearly 5,000 council seats will be up for grabs, as well as a baker’s dozen of mayoral contests, including the contest for Mayor of London.

It will be an especially important test for Sir Keir Starmer, for whom this will be his first election as leader. Oppositions usually perform relatively well in local elections as some voters use them to express their dissatisfaction with the government of the day. That, however, was a pattern from which Sir Keir’s predecessor, Jeremy Corbyn, never significantly profited. In the four annual rounds of English local elections that took place during his tenure as Labour leader (in 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019), the party never put in a performance that was indicative of being much more than evens with the Conservatives across the country as a whole.

Sir Keir will want to show that under his leadership Labour is doing better than that. However, the omens do not look favourable.

At no point since Sir Keir became leader twelve months ago has Labour been consistently ahead in the polls – the best it managed was to be neck and neck with the Conservatives last October. Since then, however, the Conservatives have been opening up a seemingly ever-widening lead in the polls. By the end of January they were a couple of points ahead of Labour. That lead then widened in February to six points and it now stands at eight.

True, at this point Mr Corbyn’s modest electoral record potentially comes to Sir Keir’s rescue. When the local elections were held in 2017, Labour was as much as nineteen points behind the Conservatives in the polls, though in the event the party’s performance in the local ballot boxes was rather better than that. So even if Labour did little better than their current standing in the polls the party could still be making gains in those places where the previous contest was held in 2017 – and these account for around half of the seats up for grabs. Under this scenario the party might still capture some of the metro mayor contests that the party lost narrowly in 2017 (specifically, Tees Valley, West of England, and West Midlands), and also deny the Conservatives control of one or two county councils (such as Derbyshire and Lancashire) – even though the party is trailing quite badly across the country as a whole.

Yet at the same time even Mr Corbyn’s modest local election record could also prove a source of embarrassment for Sir Keir. On the occasion of the local elections in May 2016 – Jeremy Corbyn’s first round of local elections as leader – Labour was only three points behind in the polls, and performed somewhat better than that in the local ballot boxes. Consequently, in those places where the elections should have been held last year Labour appear at the moment to be at risk of losing significant numbers of seats (and potentially some councils such as Bristol and Plymouth). Doubtless the party might hope that the gains it might make elsewhere would help cloak any losses it suffers in these contests, but underneath the surface we might discover that the party has in fact fared less well in its first local election outing under Sir Keir Starmer’s leadership than it did under Jeremy Corbyn’s.

So why are Labour apparently at risk of suffering such an embarrassment? During the last twelve months, the party has seemingly been pursuing a two-pronged strategy. First, it has focused on questioning the government’s handling of the pandemic, trying to raise doubts in voters’ minds about its competence. Second, the party has largely kept quiet about Brexit – indeed the party voted in favour of the trade deal with the EU that the government concluded in December last year and has said relatively little about the difficulties it has created for some exporters. Its aim (the merits of which are discussed and evaluated in this article in IPPR’s Progressive Review) has been to try and reconnect with those of its former supporters who voted Leave in 2016 and who subsequently have switched to the Conservatives.

Much of the rise and fall in Conservative fortunes during the last twelve months has mirrored voters’ evaluations of its handling of the pandemic. Both fell heavily in the wake of the row about Dominic Cummings’ trip to Durham, and dropped yet further as the prevalence of COVID19 increased once again in the autumn. Meanwhile, Opinium’s polls have consistently found that those who currently support the Conservatives are more likely than those who voted Conservative in 2019 to say that the government is handling the pandemic well – a pattern that implies that those who voted Conservative in 2019 but would no longer do so now are more likely to be critical of the government’s performance.

However, drawing voters’ attention to the government’s difficulties in handling the pandemic can only be an effective strategy for so long as the government is not thought to be doing well. And thanks to the perceived success of the roll-out of the COVID-19 vaccine programme, for the time being at least the government is now getting plaudits for its handling of the pandemic – and an accompanying boost in its electoral support.

Indeed, there have also been signs in recent weeks that the greater speed and efficiency with which the UK has been able to deliver its vaccine programme as compared with the EU (together with the dispute with the EU over vaccine exports) may also have had some influence on attitudes towards Brexit itself. Even though the final stage of Brexit had been completed, in January and February YouGov were still finding on average that as many as 47% thought that in hindsight the decision to leave the EU was wrong and that only 41% believed that it was right. More recently, however, these figures have been 45% and 43% respectively. In their most recent poll Kantar have reported that (after leaving aside Don’t Knows) only 45% would now vote to rejoin the EU, whereas their two previous polls found that 47% and 50% would do so. Meanwhile, after finding in three readings taken after the trade deal was unveiled that 51% would still prefer to Remain in the EU, Deltapoll’s two most recent readings put the figure at 48%. The company has also reported that as many as 27% of Remain voters say that the row with the EU over vaccine supply has made them more in favour of Brexit while just 15% take the opposite view (see also here). It may well be that the vaccine row cut through with some voters in a way that the finer details of the trade agreement with the EU may not have done.

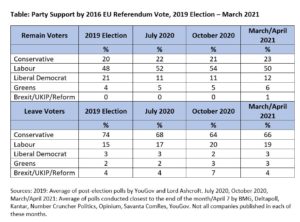

What, though, of Labour’s second strategy – to reconnect with Leave voters by accepting the fact that Brexit is done and dusted? In the following table, we assess the party’s success or otherwise in achieving this objective by tracing the level of support for the parties since the 2019 election among Remain and Leave voters separately. We show, in particular, the position in July last year, after the first wave of the pandemic was over, in October of last year, when, at 40%, Labour’s support reached its highest level yet since the election, and then in the most recent set of polls conducted in late March and early April.

The table reminds us, first of all, of the extent to which Labour was reliant on the support of Remain voters. According to polling conducted immediately after the election by YouGov and Lord Ashcroft, the party secured three votes from Remain supporters for every one secured from Leave voters. There has been little sign of any significant change in that picture. At the height of its popularity in October of last year, support for Labour had, indeed, increased on average by five points among those who had voted Leave in 2016. But at the same time, the party’s support had increased by much the same amount – six points – among Remain voters. In short, support for the party had increased by much the same amount among both Remain voters and Leave supporters. The position is little different now – the party’s support is four points up on 2019 among Leave voters, but also by two points among Remain supporters.

In short, accepting Brexit and largely avoiding the subject has so far yielded Labour little success in closing the Brexit divide in its support. This is despite the fact that there has been some sign that the Conservatives have found it somewhat more difficult to retain the support of Leave voters than their Remain counterparts (a pattern that may be accounted for by the fact that the party’s Leave supporters appear to have been more critical of its handling of the pandemic). Despite its current stance on Brexit Labour is still predominantly a party of Remain supporters most of whom, even with the recent decline in the popularity of EU membership, have not as yet changed their minds.

This pattern has implications for Labour’s prospects in the local elections. The years of debate about Brexit between 2015 and 2019 occasioned a significant reshaping of the character of support for the Conservatives and Labour. The Conservatives became markedly more reliant on Leave supporters, Labour relatively more dependent on Remain voters. Yet the 2016 local elections took place seven weeks before the EU referendum that instigated this realignment, while the trend was only partially in place in 2017. The fact that Labour is still predominantly backed by Remain supporters means that while Labour might well record significant advances in Remain-inclined parts of England (and most obviously so in the London Mayoral election) the party might find itself suffering losses once more in the Leave-inclined parts of England where the party came so badly unstuck under Jeremy Corbyn.

Brexit may be done, but it could still cast a significant shadow over Sir Keir Starmer’s hopes of demonstrating that his party is on the road to recovery.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

The only way that the population can come together over. Rexit, would be for Remainers to accept and respect a result of a referendum that was significantly based on lies, xenophobia and racism. That is quite literally an impossibility.Report

“Gut feel” says the present state of civil war within Labour needs to be factored in when reaching judgements about the likelihood of Starmer’s Labour doing comparatively well or badly in May’s elections.

Something like 248 of Labour’s 600 or so CLPs (constituency organisations) have expressed varying degrees of dissent or outright revolt over “guidance” they’ve received from Labour’s acting General Secretary (David Evans). Many CLPs and Labour members have been suspended. In some instances “shadow” CLPs have formed, in defiance of HQ or regional suspensions. Some CLPs and members feel they’ve been treated so badly by HQ they’re unwilling to campaign locally for candidates chosen by HQ, against their wishes.

To the extent that local support by local people matters when fighting an election, the party now seems to be fighting with one hand tied behind its back. Report