One key feature of the 2017 election was that the Conservatives gained ground among those who voted Leave while the party lost support among those who backed Remain. At the same time, Labour advanced more strongly among Remain voters than Leave supporters. But what happened in the 2019 election? Did those trends continue yet further or were they in any way reversed?

The first of the evidence necessary to address this question is now available, thanks to polls conducted by Lord Ashcroft and YouGov, both of whom also undertook similar exercises after the 2017 election. Lord Ashcroft interviewed online between 11 and 12 December just over 13,000 people who said they had cast a ballot. The results can be compared with those of a similar exercise from the same stable that interviewed 14,000 voters between 6 and 9 June 2017. Meanwhile, YouGov interviewed nearly 42,000 people between 13 and 16 December, the results of which can be compared with a poll of over 52,000 people conducted by the company between 9 and 13 June 2017.

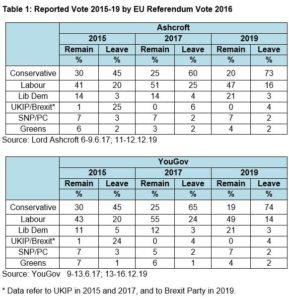

The two pairs of polls report the vote choice in both 2017 and 2019 of those who voted Remain in 2016 and those who backed Leave. In both cases, too, the 2017 poll also gives information on how Remain and Leave voters behaved in 2015, a year before the EU referendum. This means that in Table 1 we are able to show the trend over the last three elections in the vote choices of Remain and Leave supporters.

Both poll series show much the same pattern. Support for the Conservatives increased among Leave voters and fell among Remain voters between 2017 and 2019, and in so doing continued the trend that had already been in evidence between 2015 and 2017. As a result, for every one Remain voter who supported the Conservatives in 2019 there were nearly four Leave supporters who did so. In 2015, the equivalent ratio was just one to 1.5. During the last four years, the electoral base of the Conservative party has been transformed from one that, on balance, was moderately Eurosceptic to one that is now predominantly so. As a result, the foundations of the ‘People’s Government’ the party has now formed rest very heavily on that section of the public that voted Leave.

In Labour’s case, the refashioning of the party’s vote has not been so dramatic but has still been substantial. It fell between 2017 and 2019 among both Remain and Leave voters, but much more so among those who voted Leave. In contrast, the party’s vote had increased among both groups between 2015 and 2017, but more so among Remain than Leave voters. As a result, for every one Leave voter whose support the party won in 2019 there were around three Remain supporters backing the party. In 2015, the equivalent ratio was more like one to two. One of the legacies of Jeremy Corbyn’s tenure as leader is a Labour vote that has become markedly more Europhile.

The Liberal Democrat vote has become more Europhile too. After what in 2017 was largely a repeat of the party’s performance two years previously, all of the increase in the party’s support between 2017 and 2019 was secured among those who voted Remain. As a result, what has always been Britain’s most Europhile party in terms of its policy position is now the most Europhile party in the country in respect of the electoral support it enjoys too.

The Brexit process has, then, clearly had a significant impact on the character of the support for all three of Britain’s largest political parties (in terms of votes won) at the 2019 election. That in turn means that how people voted was more likely to reflect which side they backed in the 2016 referendum.

In the case of Remain voters, the change was a marginal one. According to Lord Ashcroft, in 2019 79% of Remain voters supported a party that was in favour of holding a second referendum, up from the 75% who supported one of those parties in 2017 (though, at that point, not all of those parties were in favour of a second ballot). YouGov put the figures at 78% and 81% respectively.

However, in the case of Leave supporters, the increase in the extent to which they voted for a pro-Leave party is very marked. According to Lord Ashcroft, 77% of Leave voters supported either the Conservatives or the Brexit Party this time around, whereas just two-thirds (66%) backed either the Conservatives or UKIP in 2017. Similarly, the equivalent figures for YouGov are 69% and 78% respectively.

While not everyone’s vote was influenced by their views about Brexit, the Brexit impasse of the last two years and the circumstances under which the 2019 election was called do seem to have ensured that the issue was especially high on voters’ agendas when they decided how to mark their ballot papers.

Yet, crucially, Remain and Leave voters expressed their views very differently – and it is this difference and the impact it had on the operation of the electoral system, not the balance of opinion of Brexit, that has been decisive in ensuring that Britain now has a pro-Brexit government that should be able to deliver Britain’s withdrawal from the EU by the end of January.

At 47%, the total vote cast for the two pro-Brexit parties was rather less than the 52% that went to parties in favour of some kind of second EU referendum – a balance in line with the small lead for Remain in our poll of polls of vote intentions for a second Brexit referendum. However, as we have seen, Leave voters mostly plumped for the Conservatives, while Remain voters scattered their favours between Labour and the Liberal Democrats – and, north of the border, the SNP. It is that difference that delivered the Conservatives a 12-point lead over Labour that, under the ‘first-past-the-post’ electoral system was more than enough to give Boris Johnson a handsome overall parliamentary majority. It now remains to be seen what kind of Brexit he manages to deliver.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

We should remain.It’s good for Europe and us.We will be poorer

Both cultural and spiritually, let the economics.A Labour supporter.Report

@BizzOX14

Are London votes somehow special or different to other UK votes?

Removing outlier pocketed groups – so long as it leaves a large enough UK vote percentage (ideally +70%) – to provide good insight to a majority trend of the UK population would still be worthwhile IMHO. If however removing outliers results is showing no majority that fits, then is it really a trend? That would probably inform us that these Recorded Vote polls (by Ashcroft & YouGov) have unfortunately recorded polarized results that contradict the facts of total votes we already know from the Ref and 2019 GE.

Unless I am mistaken, the excellent non-partisan analysis done here by John Curtice is suggesting from the Poll of Polls, the Pre GE 2019 opinion polls, the Recorded Vote polls and the GE 2019 result that Johnson has a large First past the Post majority now, but from this analysis he wouldn’t have had a Proportional Representation majority for a Pro-leave stance, and would have lost an EuRef2 vote – which as the figures stand seems very much the case. I was trying to show how I believe the figures from the Recorded Vote polls aren’t entirely coherent for Scotland with votes that are point of fact, not polls. And you have made the same claim about London (pressumably Pro-Remain party votes that are missing from Recorded Vote polls), but unfortunately you didn’t numerically make the argument (to give your definition of London, as a region, to show actual missing votes for remain parties) to illustrate London is an outlier like Scotland.

Instinctively, Mr Johnson and Mr Cummings have read the EU Referendum and GE election results correctly , in the face of election polling that has struggled with the Kingdom’s polarization, and the polls only really seem to catch up on exit polling now IMO. Unfortunately, if the polling methods are inadequate to deal with such polarization then non-partisan experts like Mr Curtice can only analyse the polled data available and draw the resulting conclusions.Report

@Janet

I’m Scots born, and all my family and wider family are Scots, but I’ve lived all my life in England. Speaking to mum that lives in Scotland, she would echo your point that no-one is talking about it, and in many ways from the discussions she has with people about independence, anecdotatlly, it would seem that the grass roots support for Scottish independence isn’t an anti-UK & Pro-EU stance as is the official SNP line, but an actual independence of everyone – which obviously isn’t anything but a hardship option, now that the North Sea oil money isn’t a silver bullet – unless Scotland sued the UK for historical revenues, which isn’t going to happen. Report

In Scotland where I live, the question of Scotland having to re-apply to join th EU, is hardly ever discussed. I don’t have any statistics, but I think a great many people here think that after independence, Scotland will just pass seamlessly into the EU. No one is broaching the subject of GDP, oil prices (we’re supposed to be carbon-neutral REALLY soon!) and the Barnet formula money that we will no longer receive from central government. A pre-referendum indyref2 anyone?Report

Here’s the weirdness Paul – By the same logic London (~60/40 in 2016 referendum) and larger than Scotland is an outlier as well so you should remove that too. Report

What’s weird about saying Scotland is an outlier? proven by missing votes for Conservatives (or even by the failure of Swinson to get re-elected) neither outcome would be the case if Scotland’s voting trended with the rest of the UK – inline with the Recorded Vote polls above (unless I’ve made a mathematical mistake or numbers I’ve sourced are wrong).

Analysing again with a small (8.5%) outlier removed, surely gives insight into the wider trend of the 91.5%, even if it doesn’t accurately provide a result, no?

Or are you suggesting that Ian Blackford prioritizing his desire for an IndyRef2 in PM’s questions (for the SNP) isn’t their first priority, still? “Can’t leave the UK without also leaving the EU,” isn’t contested in Scotland is it?Report

“At 47%, the total vote cast for the two pro-Brexit parties was rather less than the 52% that went to parties in favour of some kind of second EU referendum – a balance in line with the small lead for Remain in our poll of polls of vote intentions for a second Brexit referendum.”

Taking each party’s manifestos and sounds bites as fact, it would be fair to include the SNP on the side of Remain – as is presumably the case with the assertion above. But the reason the SNP party exists is to leave the UK, and that can’t happen unless they also leave the EU (with or without the UK Brexiting, and then re-applying). Nicola Sturgeon openly acknowledges this to be Scotland’s reality… which should then surely mean that the SNP’s 3.9% of the national vote would either be removed (as Brexit neutral) or stacked with Leave. In either situation, Pro-Brexit parties votes would either become ~49% or ~51%, respectively.

Further scrutiny of the Scots Leave vote shows it isn’t consistent with the rest of the UK Reported Vote polls listed above that landed a total of 77 – 78% of 2016 Leave votes for Pro-Brexit parties at this 2019 GE. Instead, scaling the Scotland turnout of 2019 GE by the split(leave/remain) in Scotland for 2016 Ref, 100 000 more votes should have been cast for the Conservatives, Brexit Party or UKIP. Further suggesting that in Scotland voting wasn’t about Brexit and more about Independence or other issues like First minister popularity. On that basis, If you then removed Scotland’s votes completely (~8.5% of the UK vote) from the figures. Comparing Pro-Brexit and Pro-Remain votes is then getting close to the actual 2016 Ref result split… and maybe even a wider split if factoring in a ~5% drop in turnout (outside of Scotland) that would appear to be votes from pro-Leave UK countries, when comparing turnout between 2016 ref and 2019 GE.Report

Some weird logic here!Report