The latest poll from Redfield and Wilton Strategies for UK in a Changing Europe shows something of a drop in support for re-joining the EU. Once those who say ‘don’t know’ or indicate that they would not vote are left aside, 56% now say they would vote to re-join, while 44% state they would back staying out. That represents a three-point swing in favour of staying out as compared with the previous poll in October – and indeed as much as a five-point switch since that undertaken in August.

On its own this movement might be thought somewhat inconsequential. Perhaps it could be no more than the product of the random variation to which all polls and surveys are subject. However, it is not an isolated finding. Most other polls have recorded a fall in support for re-joining in recent weeks.

In their last two polls, Omnisis/WeThink, who ask people every week how they would vote in another Brexit ballot, have put support for re-join at 57-58%. In contrast, four of the five readings they took in November put the figure at 60%. Deltapoll, who also poll on the subject every week, now suggest that only 52-53% would vote to re-join. In November their average was 57%. Meanwhile, in their latest monthly reading BMG put staying out narrowly ahead, by 51% to 49%. This represented a swing of three points against re-joining and was the first poll since May 2022 to put staying out ahead.

Are there, then, any clues in the finer details provided by the Redfield & Wilton poll as to why re-joining may have become somewhat less popular?

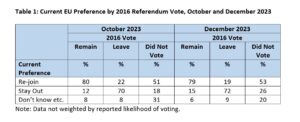

The swing appears to have occurred irrespective of how people voted in 2016. Table 1 shows the relationship between how people voted (or did not vote) in 2016 both in October and in our latest poll. As compared with two months ago, those who voted Remain in 2016 are now three points more likely to say they would vote to stay out. Equally, those who backed Leave are three points less likely to state they would vote to re-join. Meanwhile, support for staying out has increased by as much as eight points among those who did not vote seven years ago.

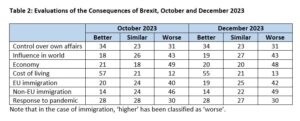

Yet there is little sign of any marked change in voters’ evaluations of the consequences of Brexit. Table 2 shows, for the three key issues in the 2016 Brexit debate, the economy, sovereignty, and immigration, how voters regard those consequences now and two months ago. Also included is how voters view Brexit’s impact on the handling of the pandemic, an issue which we have previously shown has some influence on Leave voters’ current Brexit preferences.

The figures for the two months are very similar to each other. There is certainly no consistent evidence that the consequences of Brexit have come to be regarded more favourably in recent weeks. Voters are still inclined to believe that, thanks to Brexit, immigration is higher and that the economy has suffered, while they are divided on whether or not it has given Britain more control over its own affairs.

If how people would vote in another referendum has changed but evaluations of the consequences of Brexit have not, there must have been a change in the relationship between people’s evaluations of Brexit and how they would vote in another referendum.

We have previously reported that, for 2016 Leave voters, statistical analysis reveals that their current Brexit preference is most strongly related to their perceived impact of Brexit on (i) Britain’s economy and (ii) how much control Britain has over its own affairs. In fact, the equivalent analysis among those who voted Remain in 2016 reveals that these two evaluations are the ones most strongly related to their current Brexit preference too. Meanwhile, the economy also appears to be the central issue for those who did not vote in 2016.

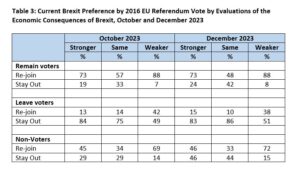

Table 3 therefore looks more closely at the relationship between people’s evaluations of the economic consequences of Brexit and how they would vote in another referendum.

One striking pattern stands out. Among all three groups of voters, the swing in favour of staying out of the EU since October has been most marked among those who think the economy is in much the same state as it would have been if Brexit had not happened. In the case of 2016 Remain voters there has been a nine-point increase in support for staying out among those of that view, while among Leave supporters and non-voters the equivalent figures are 11 and 15 points respectively.

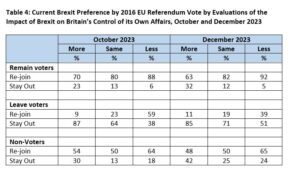

Table 4 undertakes the equivalent analysis of people’s evaluations of the impact of Brexit on Britain’s ability to control its own affairs. Here too, among 2016 Leave voters and non-voters at least, there has been a marked increase (of seven and twelve points respectively) among those who think Brexit has not made much difference, though in the case of Leave voters those who think Britain has less control are also especially less likely to say now that they would vote to re-join the EU.

Two implications follow.

First, it is far from certain that another referendum would produce a majority for re-joining. Despite widespread doubts about the benefits of Brexit, the anti-Brexit lead in the polls is not that large, differs between polling companies, and is far from invulnerable.

Second, much might rest in any referendum on the preferences of those who reckon Brexit has not made much difference. Seemingly many of them could yet decide it would be better for Britain to make the best of the bed it has now made for itself rather than pursuing the uncertain prospect of trying to reclaim its old one.

This post also appears on the UK in a Changing Europe website.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

Brexit, there is little doubt that leaving the EU and single market was an idiotic thing for UK to do, but the Conservative Party supported it against the wishes of their leader, who did the right thing and resigned because of the loss. It’s noticeable that the all the Brexiteers have either been disgraced, dismissed or resigned leaving any future government to make the best of what they have been left with. It’s obvious that UK should now get as close to the EU, to UKs advantage, as it can. After all the EU is only some 20 miles away, as opposed to the Trans Pacifit deal half a world away.Report

I see that the Poll of Polls is now (13/1/24) back at 59% pro-EU. Was John Curtice’s article a little premature? His claim that “re-joining may have become somewhat less popular” is not it seems confirmed by the latest data.Report

I wonder what the effect would be if Labour were to declare that they had concluded (in 2026, say 10 years after the referendum) that Brexit was a mistake. After all the most extraordinary fact about all the surveys John Curtice has been watching for some years is that a majority of people consistently say we should re-join the EU, even though no party (other than the SNP) says it wants to re-join. Given a little political leadership, I wonder if support for this cause would surge.Report

Yeah – ok – polls and “polls of polls.” Every one of those (including “WhatUKThinks:EU” got the result WRONG:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opinion_polling_for_the_United_Kingdom_European_Union_membership_referendum#Polls_of_polls

So excuse me if I question your rationale whilst also thinking the Labour party think the same and THAT’S why they’re not following your suggested policy!Report

Seems a bit of a fail of the democratic system that a majority view has no mainstream political representation at all outside Scotland.

Remember the “will of the people”? Turns out it is really an elderly, declining but very vocal minority which peaked at 37% some eight years ago.

Starmer says he’ll make Brexit work. Presumably at some point the validity of that claim will be assessed. I could see perhaps moves towards the single market being a vote winner in the election after next.

We could also see a very different incarnation of the Tory party by then. The “reform threat” will focus minds in that there aren’t enough votes on the lunatic fringe (and as stated they are declining) and they can never be right-wing enough for the UKIP fringe but that there’ll forever be a 10-15% of their base which can be syphoned off. It could be the vote squeeze might see a new Tory enthusiasm for proportional representation even. That could be the way back in the game.Report