Brexit emerges as a little less unpopular in the latest poll by Redfield & Wilton for the UK in a Changing Europe. Once those who say Don’t Know are set aside, 59% say they would vote to re-join the EU, while 41% indicate that they would vote to stay out. That represents a swing of 3% from re-join to stay out since our previous poll in August. Indeed, it is the first time this year that the percentage who say they would vote to re-join has been below 60%. This trend is consistent with the findings of other polls, which in recent weeks have typically been recording slightly lower levels of support for re-joining the EU.

This swing away from re-joining has been accompanied by a range of slight improvements since August in voters’ perceptions of the consequences of Brexit. For example, 21% now think that the economy is stronger than it would have been otherwise, compared with 19% in our previous poll. Similarly, 34% now feel that Brexit has given Britain more control over its own affairs, up from 32% in August. The proportion who think EU immigration has fallen as a result of Brexit has edged up from 18% to 20%, though, at the same time, the proportion who believe that ‘illegal’ immigration has increased now stands at 48%, its highest level since we first started asking the question in February.

But which, if any, of these evaluations matter for Leave voters’ current preferences for being inside or outside the EU? Are their minds still focused on the three issues – sovereignty, the economy, and immigration – that research suggests were central to the choice voters made in 2016? In particular, are these the issues that help us understand why some Leave voters now have a different attitude towards EU membership than the one they expressed seven years ago?

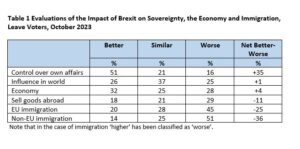

Table 1 shows how those who voted Leave in 2016 now evaluate the consequences of Brexit for the three key issues in the 2016 referendum. In each case respondents were asked whether, with the UK outside the EU, the position now is better/higher/more than it would have been otherwise, worse/lower/less, or similar to what would otherwise have happened.

Leave voters have very different views across the three issues. They are inclined to believe Brexit has enabled Britain to have more control over its own affairs, a sentiment that might be thought central to sovereignty, although they are less certain that Britain has more influence outside its borders. On the economy, optimists and pessimists largely balance each other, albeit there is some uncertainty about the impact of Brexit on companies’ ability to sell goods abroad. However, whatever hopes they might once have had that immigration would fall appear to have disappeared. Around half think that immigration from both the EU and from outside has increased.

Leave voters have very different views across the three issues. They are inclined to believe Brexit has enabled Britain to have more control over its own affairs, a sentiment that might be thought central to sovereignty, although they are less certain that Britain has more influence outside its borders. On the economy, optimists and pessimists largely balance each other, albeit there is some uncertainty about the impact of Brexit on companies’ ability to sell goods abroad. However, whatever hopes they might once have had that immigration would fall appear to have disappeared. Around half think that immigration from both the EU and from outside has increased.

This would seem to suggest that the main reason why some Leave voters have changed their mind about Brexit is the perception (and, indeed, the reality) that immigration has increased. However, this is to assume that Leave voters’ views of what has happened to immigration are related to the probability of them changing their mind about Brexit. That proves not to be the case.

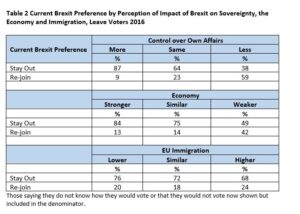

In Table 2 we show how those who voted for Brexit in 2016 say they would vote in a referendum on re-joining versus staying out of the EU broken down by their perception of the impact of Brexit across the three main issues of the referendum campaign. The perceived impact of Brexit on the level of control is clearly related to whether Leave voters would now vote to stay out of the EU or to re-join. No less than 87% of those who think Britain now has more control would vote to stay out, compared with just 38% of those who feel we have less control.

Much the same picture is true of perceptions of the economy. Among those Leave voters who think the economy is stronger, 84% would vote to stay out, compared with just 49% of those who think the economy is now weaker. However, how Leave voters would vote in a referendum is largely unrelated to their perception of whether immigration from the EU is higher or lower. Among those who think that immigration is lower 76% would vote to stay out, little different from the 68% level among those who think that immigration is higher. Analysis of the impact of Leave voters’ evaluations of the impact of Brexit on non-EU immigration or, indeed, of ‘illegal’ immigration produces much the same result.

We might wonder how important our three issues are compared with the range of other ways in which Brexit might be thought to have made a difference, on which our poll also collected a great deal of evidence. In fact, a statistical analysis in which we ask the computer to pick out the evaluations that are significantly related to how Leave voters would vote now reveals that perceptions of control followed by the economy are, indeed, the two most important influences. Immigration does not feature at all.

Just one other perception plays any kind of role at all – the perceived impact of Brexit on Britain’s response to the coronavirus pandemic. On this Leave voters are inclined to feel Brexit has been beneficial – 44% believe that Britain’s response was better as a result of Brexit, while only 18% feel that it was worse. Meanwhile, as many as 85% of those Leave voters who think that the response has been better would vote to stay out, compared with just 44% of those who feel it was worth. The government certainly argued, albeit the claim was disputed, that Brexit enabled it to implement a vaccine programme earlier than the EU.

Leave voters are then inclined to the view that Brexit has enabled Britain ‘to take back control’ and that perception has particularly helped ensure that as many as 70% of Leave voters would still vote to stay outside the EU. However, rather more Leave voters believe the economy has suffered as a result of Brexit, and only around one in two of those who express that view would now vote to be outside the EU. It is that pattern that helps us understand why as many as 22% of 2016 Leave voters would now opt to re-join the EU.

Meanwhile, although Leave voters might regret the failure of Brexit to lower immigration, it seems it is a fact of life to which they are now largely resigned.

This blog also appears on the UK in a Changing Europe website

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

Another observation:

You strongly imply in your report that the data shows an improvement in support for Brexit. Does it?

Assuming you are using usual surveying techniques, then a ‘swing’ of c2% isn’t statistically relevant. ie a 2% movement either way, fits within the expected boundaries and limitations of the sample size.

[BTW – this is one of the critical mistakes made by commentators in the run up to the 2016 vote, who stated Remain polling showed a ‘small but clear lead’, when in reality the polls did not show a Remain lead as it was too close to call].

Please confirm and, if correct, amend your findings accordingly.Report

Any chance you might provide the same data for Remain voters and voters as a whole?

Or when you write about the ‘Brexit debate’, do you only care about what Leave voters feel?Report