It is now two years since the UK left the EU single market and customs union following the conclusion of a Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) between the UK and the EU at the very end of 2020. That agreement was the final stage of a Brexit process instigated by the majority vote to Leave in the June 2016 referendum.

However, there is no guarantee that the popularity of a policy will survive its implementation. And it appears that Brexit has not survived the test of time at all well so far as voters’ evaluations of its success are concerned.

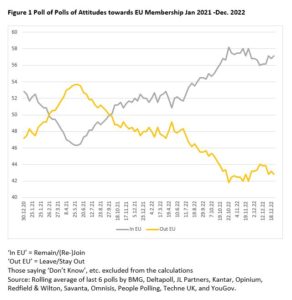

Figure 1 displays for the last two years a rolling average of the last six polls that asked people how they would vote in another referendum on EU membership (those saying Don’t Know are excluded from the calculations). In the initial months of 2021 these polls were a mixture of those that asked people how they would vote if faced once again with the choice between remaining or leaving the EU (see here and here) and those that asked them to choose between (re-)joining or staying outside the EU (see here and here). Subsequently, the latter approach has gradually become more common and, indeed, it accounts for all polling on the subject that has been conducted since last spring.

When the TCA was concluded, being inside the EU was actually slightly more popular than being outside. But in the ensuing months the balance of public opinion turned around. By the middle of 2021 support for being outside the EU reached nearly 54% on our rolling average, and, although the popularity of Brexit fell somewhat thereafter, at the end of summer 2021 it was still the more popular option. Accompanied as it was at the time by a strong performance by the Conservatives in polls of vote intentions, it appeared as though Brexit might no longer be a source of further dispute.

However, our graph reveals that this mood did not last. The autumn of 2021 witnessed much media coverage of shortages on supermarket shelves and in petrol stations, shortages that were widely blamed on a lack of lorry drivers as a result of restrictions arising from Brexit. Being inside the EU became the most popular option once more, such that by the end of the year 52% wanted to be inside the EU and 48% outside, similar to the position at the beginning of the year.

This more or less continued to be the position throughout the first half of 2022. But since then, in what has been a period of political and economic turbulence, support for being outside the EU has declined further. By the time that Liz Truss’ short tenure as Prime Minister concluded towards the end of October, not only had support for the Conservatives plummeted, but support for Brexit had reached an all-time low. With polling on the subject now much more regular than it had been for much of the last two years, just 43% were now saying they would vote to stay out of the EU while 57% would back (re-)joining.

That is still the position now. Rather than looking like an unchallenged ‘fait accompli’, Brexit now appears to be a subject on which a significant body of voters has had second thoughts.

A similar chronology is also to be found in the answers YouGov have obtained in response to a question they have regularly asked ever since the 2016 referendum, ‘In hindsight do you think Britain was right or wrong to leave the EU?’. While throughout the last two years more people have said the decision was ‘wrong’ than ‘right’, the gap between the two narrowed in the first half of 2021, but has widened since, and especially so in the second half of 2022.

But why has support for Brexit fallen? As a first step in answering that question we need to examine how the turnover of attitudes has changed during the last two years. There are three possibilities. The first is that there has been a decline in the willingness of those who voted Remain in 2016 to accept that the UK should remain outside the EU. The second is that there has been an increase in the proportion of Leave supporters who have changed their mind. And the third is that those who did not vote in 2016 (some of whom will have been too young to do so) have swung in favour of EU membership during the last two years.

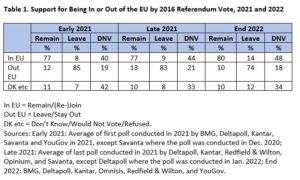

Table 1 enables us to assess which of these patterns is most in evidence. It compares the average levels of support for being in or out of the EU at the beginning and end of 2021 and at the end of 2022 separately for those who voted Remain, Leave, or did not vote.

Given that the overall level of support for being in or out of the EU was much the same at the end of 2021 as it was at the beginning (see Figure 1), it is not surprising to discover that the pattern of movement since 2016 was much the same at the end of 2021 as it was at the beginning. What should be noted is that the principal reason why, at these points in time, the overall balance of opinion was tipped slightly in favour of being part of the EU was that those who had not voted in 2016 but now expressed a view were around two to one in favour of EU membership, a pattern that had been in evidence for much of the Brexit process. Their preferences more than compensated for the fact that at this point the proportion of Remain voters who now backed being in the EU was, in fact, a little lower than the proportion of Leave voters who wanted to stay outside.

However, during the last year the proportion of Leave voters who back staying outside the EU has fallen by nine percentage points, from 83% to 74%. In contrast, there has only been a marginal increase in the proportion of Remain voters who would now vote to join the EU, while the same is also true of those who did not vote in 2016. It is now Leave voters rather than their Remain counterparts who are more likely to have changed their minds about Brexit – and it is the decline in support for Brexit among those who originally voted for it that primarily explains why there has been a swing against the idea during the last twelve months.

The key to understanding the changed mood on Brexit would seem therefore to lie primarily in an examination of how Leave voters’ evaluations of the success or otherwise of Brexit have changed during the last year or so. It is to that task that our next blog will turn.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

I voted remain,and would still vote remain today. The eu was created for peace after ww2.

The tory party are bunch of liars,especially the 1st prime minister.

Quite honestly l wiI never vote tory again.Report

ALL I HAVE TO SAY IS LEAVING EU WAS THE WORSTE MISTAKE THIS COUNTRY DID, THE QUICKER WE HAVE A REFERENDUM TO RE JOIN EU THE BETTER. I NEVER VOTE: WHY? BECAUSE THIS IS WHY YOU CAN NOT TRUST CROOKED POLITICIANS LOOK AT BREXIT: BUT I WOULD VOTE THIS TIME TO RE JOIN THE EU.Report

Why are no uk parties willing to address the issue of eu membership, let alone consider another referendum on rejoining the eu? The polls strongly suggest that such a policy would have substantial public support. This support is likely to be increased by a new, active campaign pointing out the misinformation used by the leave campaign and the negative effects of leaving that are now becoming clear.Report

The resources, of all kinds, that would be required – when everything else has been neglected for so long, and desperately needs attention?Perhaps also the fact that we’d never get as good a deal as we had, which was the result of forty years of negotiations.Report

To me, it seems amazing the support for Brexit remains so high. Clearly what was promised at the time was undeliverable and events have shown it be so. The government and “opposition” keep talking as if benefits were a self-evident truth, yet give no examples. One of the main thrusts of Brexit was immigration reduction. Well here we are in 2023 and it’s increased. So what exactly was it all for? Is it now an article of faith? I don’t get it. Whatever legitimate complaints were around in 2016 seem to me to be caused by Westminster, so quite what Brexit was for remains a mystery to me.Report

I cannot understand why Labour is so timid about pointing out the failure of Brexit. Starmer said he would “make Brexit work”. This I presume means making amendments to the TCA.

However EP members have said they don’t want any cherry picking amendments and most would favour a U.K. return to the EU to encourage Hungary to stay in the EU and to send a message to Putin that Europe is solid.

I can’t understand why the LDs don’t make more of this either as this would lift their share of the vote, and would give the new anti Brexit majority in the Conservative somewhere to go.Report

Rejoining the EU as a full member is not realistic in the short term at least. However, there might be the possibility of rejoining the single market in some way. Has there been any recent polling on that possibility?Report

What is extraordinary about the current fast flowing tide of public opinion against Brexit that John Curtice reports, is that it is occurring without any political leadership. Can you think of any other cause where a strong majority holds an opinion and all the political parties turn their backs? If the Labour Party were to say “hey, you know what, Brexit’s a disaster” who knows what would happen!Report

I think the Northern Ireland situation is simple. The Johnson Government agreed the Brexit deal with the EU which included the NI Protocol and now wants to change an international agreement – unilaterally, if necessary – with strong urging to do so by the DUP. That party has held the UK Government to ransom over the Protocol by refusing to agree to power sharing without changes to the Protocol which it can accept but which Sinn Fein, its power-sharing partner, could not accept. But it is largely using the Protocol for political ends (i.e. as an excuse) as it does not want to play second fiddle in Northern Irish politics to a largely Catholic party which supports Irish independence. Well, tough on the DUP, but it lost the Stormont election and needs to grow up and accept the democratic wishes of the Northern Ireland people, as Labour and Tories have had to do for many years now in Scotland.

The EU may agree to minor changes in the Northern Ireland Protocol, but have no need to do so as it is part of a package agreed and signed by both the UK and the EU. The UK Government, urged by its DUP friends, want to change an agreement which it (OK, now under a different PM) signed and which the UK Parliament supported.

The reduced support for Brexit is a clear indication that far more people in the UK now see our leaving the EU as bad for our trade and our economy generally. They have seen a UK Government under Johnson and Truss making hostile claims about the EU and member state France in particular: over its “intransigence” and over the arrival of small boats on UK shores, neither of which are the EU’s fault: the blame lies with UK Conservative Governments.Report

This doesn’t seem to take account of the fact that older voters were far more likely to vote for Brexit in 2016, and many of them have since died, to be replaced in the electorate by new, young voters who are much more likely to support being in the EU. Are there figures showing what the impact of that is on the overall percentages? Presumably, it’s possible to ask people in polls whether they were old enough to vote in the Brexit referendum, but a little harder to estimate how many Brexit voters have since died, and the extent to which Brexit voters have died relative to remain voters.Report

What is extraordinary about the current fast flowing tide of public opinion against Brexit is that it is occurring without any political leadership. Can you think of any other cause where a strong majority holds an opinion and all the political parties turn their backs? If the Labour Party were to say “hey, you know what, Brexit’s a disaster” who knows what would happen!Report

Excellent point, Peter Chowney. I was very surprised that Professor Curtice didn’t address this point in his article.Report

The people of Northern Ireland have never been bothered about E.U. membership. The cause of the 1968 to 1998 “troubles” was how Northern Ireland would align as and where the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland would differ. In June 2016, not one would ever have voted in a way to wreck the Northern Ireland peace process.Report

I did vote to remain back in 2016, but think that now that we have left, we should not take any steps about rejoining for at least ten years from now.

One major concern is the island of Ireland.

The European Commission could be pragmatic and; at no cost to themselves nor any member; agree to no borders around the island of island; no one would travel or send goods via both halves of Ireland when travelling or sending goods between the British and European mainlands, as to do so would be more expensive and time consuming, then directly and dealing with customs dues/paper workReport