Today the UK leaves the EU, three and a half years after the original vote to do so in the 2016 EU referendum. The political difficulties in the way of implementing Brexit were finally cleared by the outcome of the general election in December, which gave the Conservatives – who were committed to the UK leaving the EU on the basis of the revised withdrawal deal that Boris Johnson secured in October – an overall parliamentary majority of 80.

Two questions inevitably arise. The first is where does the public stand on the merits or otherwise of the decision to leave? Did the Conservatives’ success in the general election affirm the result of the 2016 referendum in which a majority (52%) voted to Leave? The second is what kind of future relationship with the EU do voters – on both sides of the argument – hope will emerge from the talks on that relationship that will now be instigated between the UK and the EU?

Polling of how people say they would vote in another referendum still suggests – as it has done throughout the last two years – that the outcome of a referendum on Brexit held now would be different from the one that emerged from the ballot boxes in June 2016. Our poll of polls, based on the six most recent polls of how people would vote in another referendum, on average currently puts Remain on 53%, Leave on 47%.

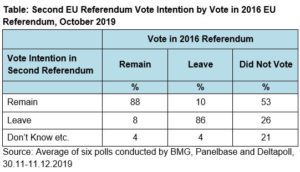

This is not because polls suggest that there has been any significant change of mind among those who voted Leave. Rather, as shown by our table – which is based on the last six polls of EU referendum vote intention to be conducted before the general election on December 12 – it is primarily because those who did not vote three years ago (some of whom were too young to do so) are around twice as likely to say that they would vote Remain as to state that they would vote Leave. The pattern, whereby over 85% of both Remain and Leave voters say that they would vote the same way but those who did not vote are more inclined to prefer Remain, has repeatedly been in evidence throughout the last year.

As we have noted before, although not everyone cast a ballot in the 2019 election voted for a party whose views on Brexit reflected their vote choice in 2016, the overall outcome of the election in terms of votes – as opposed to seats – is also consistent with the picture of a country that is still close to being divided down the middle on Brexit, but with perhaps slightly more in favour of Remain than backing Leave. While 47% of voters in Great Britain voted for parties that were in favour of leaving, 52% backed parties that felt that Brexit should not proceed without another ballot being held first. The Conservatives’ electoral success primarily reflected the fact that Leave voters largely all backed the same horse, whereas the votes of Remain supporters were divided across a number of parties. It was not a clear indication of any marked swing in favour of exiting the EU.

Still, we might ask ourselves whether, now that Brexit has been accomplished, many Remain voters will accommodate themselves to the new situation. So far only one poll of how people would vote in another EU referendum has been published since the general election. That, from BMG Research, put support for Remain at 52% and Leave on 48% (after excluding those who said, ‘Don’t Know’. That does represent a two-point drop in support for Remain as compared with the average of five previous polls that company conducted during the election campaign, but it is too small a drop for us to be rule out the possibility that the change is simply the consequence of the random variation to which all polls are subject.

That caution is reinforced by the results of the first post-election reading from YouGov of its long-standing question on whether in hindsight the decision to leave the EU was right or wrong. That found that while 40% say that it was right, 47% state that it was wrong. These figures are very similar those of 41% and 48% respectively that were reported on average by YouGov in their three previous readings, all taken at the outset of the election campaign.

But irrespective of where voters might stand now on the principle of leaving the EU, what kind of future relationship would they like the UK to have with the EU? In a contribution to a new publication by the UK in a Changing Europe programme on the post-Brexit challenges for the UK to be released next week, we report some initial findings of recent polling on this subject that NatCen has undertaken, including as part of The Future of Britain project. (More details of this research will be released in the coming weeks.)

Two points emerge. First, it is not clear that voters necessarily want the UK to depart from the regulatory rules that are currently enforced by the EU – and perhaps especially so when those rules give them rights as consumers. For example, across four surveys undertaken during the last three years – most recently in September 2019 – we have repeatedly found that over 70% are in favour of requiring ‘mobile phone companies to follow EU regulations that limit what they can charge for calls made abroad’. Meanwhile, the proportion in favour of requiring ‘British-owned airlines to follow EU rules that require them to pay compensation to passengers who have been seriously delayed’, already at two-thirds in the autumn of 2016, was nearly four-fifths (78%) in our September survey.

Second, while concern about immigration has declined, there is still widespread reluctance by voters to accept freedom of movement between the UK and the EU. In the autumn of 2016, not long after the EU referendum, nearly three-quarters (74%) said they were in favour of ‘requiring people from the EU who want to come to live here to apply to do so in the same way as people from outside the EU’. In our most recent reading, taken during the general election campaign, that figure had fallen to just under three-fifths (58%). However, that still represents a clear majority – and even among those who voted Remain supporters of ending freedom of movement outnumber opponents.

At the moment, the UK government is seemingly intent not only on ending freedom of movement, but also on seeking the freedom for the UK to diverge significantly from the regulatory standards that underpin the EU single market. However, it may be the case among voters at least that ending freedom of movement is regarded as the more important prize.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

Dear John,

I love your website.

Could someone please correct the YouGov Eurotrack data point from 20 Jan. it has 45% for leave and 40% for remain, but the raw data has it round the other way.

Many thanksReport

Hi Gerard, thanks very much for flagging this – the data has now been corrected. Best wishes, IanReport

2015 UKIP polled 3.9 million, so that’s a significant no of xenophobes to ‘win’. In fact the no of people in uk who self identify as being ‘a little’ or ‘very’ prejudiced against people of other races is around 26%.so doing the sums theres a lot of them in the figures. Some other voters wanted the illusion of sovereignty, others were incensed by ‘silly’ echr decisions(the court has nothing to do with the eu, so no understanding there) others hankered back to the old colonial past, mistakenly thinking we could rule the majority of the world again.I was surprised by a number of people still immersed in the ‘old enemy’ anti french anti german rhetoric, others genuinely believed we would be better off becoming smaller- I could go on but it serves little useful purpose. We were fed lies from both sides, some more sinister than others. So, a decision was made to remove ourselves from the biggest peace project (despite its many faults) the world has known, ever! and with the statistical advantage which would have been rejected by most countries using referendum to decide issues, knowing that such action leads to problems of internal cohesion and division. I hope I’ve gone some way to answering your question?

Report

I get that you think you are good at reading minds. I just read numbers.Report

It’s not what I think, it’s what I’ve been told, I dont make things up you know.The peace thing is my variation on a theme put forward by many. Is this a ‘ price of everything, value of nothing’ thing?Report

No, it’s a democracy thing.Report

Dont anyone be coy about the Brexit issue. Leave in its various forms was a single issue- keep foreigners out, the rest was just window dressing! The majority (1. 4 million, not 17.4) could be easily identified as xenophobic UKIP voters. The difference between leave and remain is of no pragmatic or reliable value and in my opinion should never have been used to pursue the damage leaving will do. A sad day for the now ‘little Britain ‘!Report

“The majority (1. 4 million, not 17.4) could be easily identified as xenophobic UKIP voters”

Fascinating. The 1.4 million were UKIP voters – in fact supposedly easily identified as such – while the other 16 million were, well, what exactly?Report

As Prof. Curtice has said in the past, the way the questions are worded in a poll can make a difference to the responses. The policy questions introduce the context aspect, and most people will opt for a benefit for themselves unless they understand the full context.

In addition – although ” 47% of voters in Great Britain voted for parties that were in favour of leaving, 52% backed parties that felt that Brexit should not proceed without another ballot ‘ ‘ the website How Britain voted and Why shows that only 19% of Labour voters said that believing the party would get the Brexit outcome they wanted was among their top three reasons for doing so. This casts doubt on the validity of using votes cast in the GE as a serious indicator of a Remain /second referendum desire..Report

There is a lot of misleading stuff here, especially in talking about “EU rules”. To talk about the UK or UK companies being “required to follow EU rules” implies a measure of EU jurisdiction since, obviously, UK Courts cannot rule on the exact meaning or application of EU Rules. Only EU Courts can do that.

If Parliament decides to, for example, make sure that delayed passengers get compensation, then that would be a UK Rule, not an EU Rule, and the level of compensation might be lower, the same, or higher than the EU level, and in cases of dispute, it would be settled in a UK Court without reference to the EU.

Even if a level of compensation happened to be identical to that in the EU, it would still be a UK rule and not an EU Rule. Otherwise EU regulation would be forcing the UK to apply its own law to its own citizens. That would be a pretty obvious nonsense – if the UK later changed the level of compensation to something different to the EU, would the EU then have oversight over compensation levels in the UK different to those in the EU?

The repeated coupling of consumer rights with the phrase “EU Rules” implies that without EU oversight, UK consumers won’t have those rights. They will have the rights that Parliament and UK Courts decide they have.

This ought to be obvious stuff. When we were members of the EU we used EU rules as members. Now that we have left, our rights are UK rights, even if by coincidence some of them are the same as similar rights inside the EU.Report

Yes, that’s all true, but surely the point is that a majority of voters are happy with the cited regulations as they stand, ie as made by the EU. In practical terms it doesn’t matter if we rebadge them as UK regulations – they would be the same regulations. The professor is right – ending of freedom of movement is the greater prize for a majority of voters, since they want that policy to change (which we can only do fully outside the EU) while they don’t mind the regulations on mobile phone charges and compensation for air travel delays.Report

You are completely missing the point. “Whose” regulations they are is very important because it determines whose courts adjudicate cases.

If they are “EU” regulations, then UK cases will all have to be tried in EU Courts, because only EU Courts can say what “EU” regulations really mean. And that would be true even if, for example, a UK passenger was suing a UK airline. Nor could Parliament have any power over the regulations, because then an ex-member state would be making modifications to EU law – a pretty obvious nonsense.

On the other hand, if they are UK regulations, then even if, temporarily, the wording is similar to EU wording, UK Courts will have jurisdiction, and over time Parliament can decide when and how that wording should be modified.

Oh, and this week we are watching the EU try for slip through a clever power-grab. They want to UK to sign up to what they call “dynamic alignment” which would mean that whenever the EU changes its regulations, the UK would have to make the identical change in its, which would allow the EU to claim that the UK was independent, while keeping indirect control over UK law and being able to over-rule Parliament even in domestic cases involving UK markets, and UK production sold to UK consumers and going no-where near the EU.

Is that what a country should aim for? To have a foreign entity assert control over its domestic law even when products are for domestic consumption and are neither exports nor imports. I think most people would call that a good example of a colonial empire.Report

Interesting article but as ever the Prof slips in a straight non-sequitur , this time at the end. He reports a 58% majority for ending freedom of movement and more than 70% for keeping EU regulations, THEN for some unknown reason slips in the statement that this may mean people regard ending freedom of movement as “the more important prize”. No it does not, not on those figures, Professor.Report

70% in favour of keeping EU Regs

58% in favour of ending free movement

You can’t have both is the prof’s point. Ending free movement has happened….but we are not keeping EU regsReport

But what does “we are not keeping EU regs” actually mean? Does it mean that UK owned alrlines can’t pay compensation to delayed passengers?

Clearly not. UK owned alrlines can perfectly well pay compensation to delayed passengers under UK regulations.

This is the problem with the phrase “EU Regulations”. It implies some sort of connection with the EU, when the only real connection is a coincidence of wording.Report

But UK airlines will not pay compensation. It won’t happen straightaway, but it will happen, as will, across the EU, those fun 2,000% roaming charge hikes we already get in Switzerland. Why? Because unless, by law, everyone has to behave, one won’t, and the rest will follow.Report

“Because unless, by law, …..”

I wonder if you actually get what the discussion is about. It’s not about what a particular airline or cell phone provider does, but about whose law they do it under.

Do you in the UK elect a government that enforces UK compensation under UK law, paid by a UK airline to a UK passenger?

Or do you rely on a foreign government – the EU – with the slowest growth on the planet, with the highest unemployment – a Government that can’t keep its own citizens safe, to throw its weight around in the UK and tell us how to spend our own money?

That’s what Brexit is about, you know. Do we spend our own money on ourselves, or do the Germans – sorry, the EU – to tell us how to spend it, ignoring the UK voter as they do?Report

I understand it pretty well thanks Jon. In Brentwood, we have the same safety rules as in Chelmsford. If we didn’t, we’d undercut the firms in Chelmsford. Really simple. Common rules. Level playing field. Only way to protect workers, consumers, planet, etc.

By the way, the EU only became ‘foreign’ when we left. Half of us (actually a little more than half, the better educated half, the public servants and teachers, the graduates) agree with me.Report

No, you don’t get it. Chelmsford and Brentwood are in the same legal jurisdiction, so this ‘point” is nonsense.

The real point is very simple. Having left the EU, we can choose whether to make one or another UK regulation similarly worded to an EU regulation, or choose not to.

It’s a choice. We don’t have to invite foreign courts to force us to do what we want to do. We decide what to do, after weighing the pros and cons, and then do it, just like any normal country.

And the second fallacy is about undercutting. If the EU don’t like the UK becoming more competitive, they can impose external tariffs on imports from the UK. In fact, under WTO rules that’s all they can do. Trying to establish legal jurisdiction over your trading partners isn’t on.

All you can do is to say “These goods were produced too efficiently, so I won’t import them, or will tax them.” The EU can do that, as can any country, but they would be cutting their own throats.Report

I think it is very unfortunate that in the polling there seems to be no attempt to point out that rights are reciprocal.

Was there a question asking whether Britons were prepared to lose their right to settle in other EU countries without jumping through hoops?

Were people asked if they minded losing the EHIC and 6 months of passport life?

Were they asked whether they wanted international driving permits and green cards?

I feel the polling suggested a win win situation and pushed people to Brexit.Report