A month ago, The Sunday Times ran a front-page story in which it claimed that ‘senior government figures are planning to put Britain on the path towards a Swiss-style relationship with the European Union’. Although outside the EU, a series of bilateral deals mean Switzerland has access to the single market and implements freedom of movement. The implication of the Sunday Times story was that ministers were beginning to accept that the ‘hard’ Brexit deal negotiated by Lord (David) Frost was harming the UK’s now ailing economy, and that the UK needed to seek a ‘softer’, closer accommodation.

The story has since been denied by Downing Street. However, this has not stopped opinion polls making an attempt to ascertain whether a public that appears to have become more doubtful about Brexit would welcome the UK having a closer relationship of the kind that Switzerland has with the EU. Any such mood might not only be of interest to the government but also to the Labour party, which has suggested taking some steps designed to ease the flow of trade between the UK and the EU, albeit ones that would fall well short of what might be implied by a ‘Swiss-style’ relationship.

However, the approach and the results of the polling on this subject has varied. In a poll conducted for GB News, People Polling asked its respondents whether they supported or opposed, ‘a change in our relationship with the EU to a Switzerland-style relationship [that] would involve making payments into the EU budget, adopting many single market regulations and accepting the free movement of EU nationals to work and settle in the UK’. The description might be thought to have presented the prospect in relatively unattractive terms. Even so, in the event only 28% said they opposed the idea, slightly fewer than the 32% who were in favour.

Meanwhile, in a poll for The Observer, Opinium asked people whether they supported or opposed, ‘a tailored Swiss-style relationship with the EU’ that could involve ‘• access to the European single market • participating in EU research and education programmes • removal of all documentary and identity checks and most physical checks on goods • accepting some EU legislation as part of the closer relationship • being part of the Schengen free travel area and free movement • staying outside of the European Union.’ This might be thought a more attractive description of a Swiss-style relationship and, indeed, as many as 55% said they supported the idea while only 21% were opposed.

Finally, YouGov asked people whether they supported or opposed a ‘closer deal with the European Union, similar to the deal between the EU and Switzerland, where many trade barriers between the EU and Britain were removed, there was free movement between Britain and the EU, and Britain followed many EU rules and regulations?’. This might also be regarded as a relative benign description and indeed, with 54% saying they supported the idea, and only 24% opposed, the figures were not dissimilar to those obtained by Opinium.

Two lessons might be drawn from these previous results. First, the prospect of a closer relationship is potentially not unattractive to voters. Second, however, the tone of the description has the potential to make a difference to the pattern of response. In that connection we should also bear in mind that it is not easy to provide a rounded description of a ‘Swiss-style’ relationship within the limited space of a single poll question.

We might make two further observations. First, it might be the case that voters are keener on some potential ways of softening the UK’s current trade deal with the EU than others. Certainly, further questioning by Opinium suggested that UK participation in EU research programmes (66% in favour) was more popular than agreeing to some EU legislation (53%). Second, any closer relationship would entail the UK gaining closer access to the EU single market in return for giving the EU greater access to the UK and its market. This suggests that what matters is whether the likely trade-offs in any renegotiation would or would not be acceptable to voters.

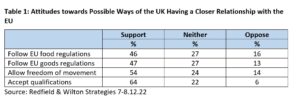

In this spirit, in its latest poll for UK in a Changing Europe, Redfield & Wilton Strategies asked whether people would support or oppose the following four distinct ways in which the current Brexit deal might be softened:

The UK adopting EU laws and regulations on food and agriculture in exchange for the EU not implementing border checks or tariffs on food products produced in the UK?

The UK adopting EU laws and regulations on the manufacturing of goods in exchange for the EU not implementing border checks or tariffs on goods produced in the UK?

The UK allowing EU citizens to freely travel, study, work, and immigrate to the UK in exchange for the EU allowing UK citizens to freely travel, study, work, and immigrate to the EU?

The UK accepting EU professional qualifications (for instance, for nursing, engineering, etc.) in exchange for the EU accepting UK professional qualifications?

Table 1 reveals that all four were relatively popular. Nearly two-thirds are in favour of the mutual acceptance of professional qualifications. Just over a half back allowing freedom of movement, and a little below half following EU regulations to ease trade with the EU. Meanwhile, even in the case of the least popular of the four, only one in six said they were opposed.

These figures present a picture not dissimilar to that obtained by Opinium and YouGov. Apparently, there might well be relatively widespread support for a closer relationship with the EU, albeit the level of support could depend on how any move in that direction is framed for voters by politicians. A framing that emphasised the potential advantages for the UK might produce a different public response than one that emphasised what the UK was conceding to the EU in turn.

Should we be surprised? One reason why not is how voters have responded when asked how close or distant the UK’s relationship with the EU should be. In Redfield & Wilton’s latest poll, 55% say that the UK should have a close relationship, while just 9% say it should be distant. These figures have varied little over the course of this year. In contrast, only 32% think that that the UK currently has a close relationship, while 24% believe the relationship is distant. In other words, on balance people say they want a closer relationship than currently exists.

Still, we might wonder what voters might mean by a close relationship. Would it necessarily extend to backing the details of a possible ‘Swiss-style’ relationship?

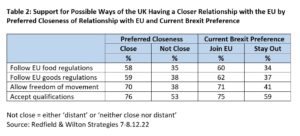

The first two columns of Table 2 reveal that those who say the UK should have a close relationship with the EU are more likely than those who do not to support each of our propositions. This is most clearly the case in respect of freedom of movement where as many as 70% of those who think the UK should have a close relationship support the idea, compared with just 38% of those who do not think it should have a close relationship. Meanwhile, although only a minority of those who do not want a close relationship with the EU support most of our propositions, even among this group, just over half (53%) support the mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

However, we can also see from the last two columns of Table 2 that those who would vote to join the EU in another referendum are markedly more likely than those who want to stay out to express support for our four propositions. And given that those who want to be part of the EU (70%) are more likely than those who wish to stay out (41%) to say that the UK should have a close relationship, perhaps the link between how close a relationship with the EU people want and their attitude towards a softer Brexit is simply a consequence of the division between those who want to re-join and those who wish to stay out?

In practice this is not the case – and especially among those who wish to stay out of the EU. Among this group, for example, 59% of those who would like the UK to have a close relationship with the EU support freedom of movement as described by our question, compared with just 29% of those who do not want a close relationship. Indeed, among the latter group, opponents (36%) outnumber supporters. There are similar if somewhat smaller differences on our other propositions, though even among Leave voters who do not want a close relationship over half (52%) support the mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

Throughout the last year, voters have regularly been telling Redfield & Wilton that the UK’s relationship with the EU should be closer than they feel it is at present. What can now also be said is that that mood is reflected in how people respond to specific proposals for softening the UK’s relationship with the EU. There might be a better reception among voters for a softer Brexit than perhaps either the government or the opposition currently realise.

A shorter version of this post is available at the UK in a Changing Europe website.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

Totally agreeReport

The Swiss option is a non-starter. The Swiss do not like it and the EU do not like it. The reason is that it is made up of a large series of bilateral agreements that makes the system overly complicated.

Personally, I believe Brexit was a huge mistake and we will need to spend years repairing the damage. We need to understand what went wrong in 47 years of membership. And we need to understand why the founding principles of the European Project are important. There will be no cherrypicking in future.

I want to rebuild our relationship with the EU in stages with the ultimate aim of rejoining. Just picking aspects of the EU we like will not succeed. Saying you want to rejoin the single market and customs union will not do. The EU probably would not allow that.

Reverse Brexit is the only long term policy I can see working. Start with small, easily attained objectives and work from that, step by step.Report

The ‘important founding principles’ you mentioned were a big part of what went wrong. They became like religious dogma to EU officials which resulted in an unwise inflexibility. Freedom of movement resulted in a huge transfer of people from eastern Europe to Britain in a very short time which was always going to cause problems. And the drive towards an ‘ever closer union’ looked like a federal power-grab by the European Commission – which it kind of was. No UK PM/opposition leader could ever sell the idea of Britain being a state in a centralized federal Europe and expect voters to elect/re-elect them.Report