One of the most noteworthy features of attitudes towards Brexit since the UK voted to Leave the European Union in June 2016 has been the relative stability of the balance of opinion. This has continued to be the case, even though the choice that would now face voters in any future ballot would be whether the UK should rejoin or stay out of the European Union, rather than whether it should Remain or Leave. Indeed, despite the change of question, today’s poll from Redfield & Wilton Strategies finds that, after leaving aside Don’t Knows, 55% would vote to stay out of the EU and 45% to join, figures that are only modestly different from the tallies of 52% Leave, 48% Remain that were recorded in the 2016 referendum.

But how do we account for the movement that has occurred? How people voted six years ago largely reflected their views on three key issues in the Brexit debate – immigration, the economic consequences, and sovereignty. So, we might anticipate that it is a change of heart on these issues that is primarily associated with people taking a different view of EU membership now than in 2016. On the other hand, other issues, such as the argument that being outside the EU enabled the UK to launch a COVID-19 vaccination programme, have since come to the fore in the Brexit debate, and perhaps it is these new issues that have persuaded some people to take a different view. Meanwhile, we might wonder whether those who voted Remain but now say that the UK should stay out of the EU have indeed changed their view about the consequences of Brexit or whether they have simply come to accept what they now regard as a fait accompli.

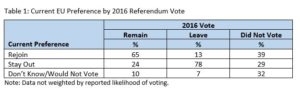

How many people have in fact changed their minds according to the latest Redfield & Wilton polling? As we might anticipate from the fact that rather more people say they would prefer to stay out than backed Leave in 2016, Table 1 reveals that those who voted Leave are more likely to back staying out of the EU (78%) than Remain voters are to say that the UK should rejoin (65%). Overall, just over seven in ten (71%) of those who voted in 2016 expressed a view about joining or staying out that was consistent with their choice six years ago, while just under one in five (18%) now take a different view.

Today’s poll asked a new set of questions designed to tap people’s perceptions of whether the UK is better or worse off as a result of being outside the EU. Hitherto, most polls that have addressed the issue have asked people what they think has been the impact of leaving the EU. However, as Brexit gradually begins to fade from the rear-view mirror of our memories, this approach will increasingly come to appear dated. Some may not remember Brexit at all! Over the longer term the question that will be pertinent is whether or not Britain feels it is better off outside the EU than it would be as part of the European club – and that is how respondents to today’s poll were invited to consider the issue.

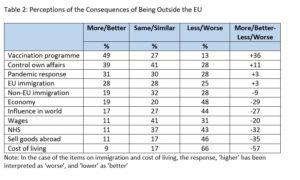

Table 2 summarises the results across the sample as a whole. The details of the question wording varied – in the case of the economy, for example, the poll asked whether the economy is ‘stronger’ or ‘weaker’ as a result of being outside the EU, while in the case of the UK’s influence in the world, it asked whether the country now had ‘more’ or ‘less influence’. To simplify matters, in the table we have put all the positive evaluations, however worded, in a column headed ‘more/better’ and all the negative ones in a column labelled ‘less/worse’. In the far right hand column we show the proportion giving a positive response minus those expressing a negative one.

It will be seen that there is a considerable variation in the balance of evaluations. While nearly half say that the UK’s COVID-19 vaccination programme has been better as a result of being outside the EU – a claim that has often been made by the UK government – two-thirds (66%) believe that the cost of living has been increasing as a result of not being a member, while under one in ten (9%) say that it has been lower. That said, those expressing a negative view outnumber those giving a positive response on seven of the eleven items in the table, suggesting that, on balance, the consequences of Brexit are viewed relatively unfavourably. Indeed, in response to another question, only 23% say that being outside the EU has had a ‘positive effect’ on the UK, while nearly twice as many (43%) say that it has had a ‘negative effect’.

These figures do, of course, make it somewhat surprising that the poll also suggests that more people would now vote to stay out of the EU than backed Leave in 2016. Part of the answer, of course, is that in answering these questions respondents may have simply been reflecting their view of the success or failure of each aspect of public policy in general rather than expressing a considered view about the role that Brexit has played in that perceived success or failure. In other words, some respondents may simply have been expressing the view that the COVID-19 vaccine programme has been a success, while, in the wake of rising inflation, indicating their concern about the ‘cost of living crisis’.

To unravel this web further, we can undertake some statistical modelling which identifies which of the perceptions reported in Table 2 are most closely associated with people expressing a different view now about EU membership from the one they supported in June 2016. This modelling reveals that two evaluations are particularly and independently associated with people expressing a different view, while many others are of little or no importance. At the same time, however, it also shows that switching from ‘Leave’ to ‘rejoin’ is more strongly linked than moving from ‘Remain’ to ‘stay out’ to people’s perceptions of the consequences of leaving the EU.

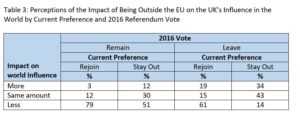

The first of the two evaluations that are linked with people taking a different view is whether being outside the EU gives the UK more or less influence in the world. The role that this subject plays is illustrated in Table 3. In the first pair of columns we compare for 2016 Remain voters the perceptions of those who now say that the UK should rejoin the EU and those who believe it should stay out. The second pair of columns undertakes the same comparison for 2016 Leave voters.

Those Remain voters who think the UK should stay out of the EU are somewhat less likely (51%) than those who believe it should rejoin (79%) to say that Britain has less influence in the world as a result of being outside the EU. That said, the perception that the UK has less influence is still the most popular view among those Remain voters who think the UK should stay out. In contrast, the views of those Leave voters who would now prefer to rejoin the EU are very different from those who wish to stay out; no less than 61% of ‘rejoiners’ feel that the UK has less influence in the world, whereas only 14% of those who would stay out take that view.

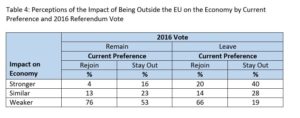

A similar picture emerges when we undertake the same analysis of the second of our two key evaluations – the perceived impact of being outside the EU on the economy (see Table 4). Those Remain voters who say the UK should stay out of the EU are somewhat less likely (53%) than those who would like to rejoin (76%) to say that the economy is weaker as a result of being outside the EU, but, even so, over half back that point of view. In contrast, whereas just 19% of those Leave voters who would stay out of the EU believe that the economy is weaker as a result of being outside the EU, as many as 66% of those Leave voters who would rejoin take that view.

Statistical modelling also suggests that perceptions of whether Britain has more or less control over its own affairs makes a difference, at least among Leave voters. As many as 71% of Leave voters who would stay out say that Britain has more control of its own affairs as a result of being outside the EU, compared with just 28% of those who would now prefer to rejoin. (In contrast, just 33% of Remain voters who would stay out feel that Britain has more control.) Between them these findings suggest that two of the three issues that played a significant role in the 2016 referendum – sovereignty and the economy – are still playing a role in influencing people’s attitudes towards the principle of EU membership.

But what of the third issue – immigration? This, in contrast, appears no longer to be helping to shape attitudes towards Britain’s relationship with the EU. For example, just 31% of those Leave voters who wish to stay out of the EU think that immigration from the EU is lower as a result of being outside, little different from the figure of 28% among those who wish to rejoin. While Leave voters may still prefer to see lower levels of immigration than Remain voters, it looks as though they no longer connect that preference with the question of whether Britain should be in or out of the EU – not least, perhaps, because even though the UK is now outside the EU 46% of them still feel that there is too much legal immigration from the EU.

Meanwhile, despite being seen by many as a success, there is little relationship among both Remain and Leave voters between their current view on EU membership and their perceptions of the impact that being outside the EU had on the success or otherwise of the COVID-19 vaccination programme. Even among those Remain voters who would prefer to rejoin the EU, 35% believe that the vaccination programme has been better as a result of being outside the EU, only a little below the equivalent figure of 51% among those who would stay out – and it is a gap that can be accounted for by the views that these two groups of voters express towards the issues of the economy and the UK’s influence in the world. There is a similarly modest difference between Leave voters who would like to stay out (72%) and those who would rejoin (58%). It seems that the vaccine rollout has not become a key consideration in people’s attitudes towards EU membership.

Just as notable is the fact that even on those issues where evaluations of the consequences of being outside the EU are linked to people expressing a different view on EU membership than they did in 2016, the link is much weaker among Remain voters than Leave voters. This suggests that while many of those Leave voters who would like to rejoin the EU have now come to a different view about the consequences of being outside the EU, many of the Remain supporters who now say that the UK should stay out are doing so despite still taking a relatively negative view of the consequences – and that their support for staying out represents more of an acceptance of a fait accompli than an endorsement of the decision to leave. In any event, the pattern we have uncovered certainly helps explain why, according to today’s poll, rather more people would prefer to stay out of the EU than backed leaving in 2016 despite the fact that, on balance, voters as a whole so far at least take a relatively negative view of the consequences of Brexit.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

Thoroughly depressing not least in reading that some Leave voters are still not satisfied with the decimation on EU immigration and on free movement both in and out of the UK which Brexit has brought about. Report

Interesting, but why has the Peace Dividend of the European Union not been noted?

I remember hearing Churchill’s speeches during the war, and I remember the vital importance of the United Kingdom being led by a Conservative administration which was at the basis for the universal declaration of human rights, published in the years after the war. And that was one of the steps that eventually led to the very existence of the European Union.

Putin’s actions have upended global, European, and national politics – including politics of Brexit. It is blindingly clear that we should rejoin ASAP, in parallel with the tidal wave of emergency request to join, by Ukraine. Any discussion of UK prospects after this war in Ukraine, must reconsider Brexit. UK has been weak, isolated, indecisive and too slow. Churchill had no such problem, and wanted union with France in 1940. Postwar he wanted a sort of United States of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/16806981f3

Churchill knew we would be stronger together.

Report

Interesting analysis but there is nothing on the Peace Dividend, which is a sad omission. As one who is old enough to remember the war and the desperate hope for a peace settlement thereafter and to remember hearing Churchill’s speeches live, I know how very important was the peace dividend and how the then Conservative government really was leading the world in setting up the Universal Declaration of Human Rights etc soon after the war. Soon thereafter the steps were started that eventually led to the existence of the EU.

Putin’s actions have upended global, European, and national politics – including politics of Brexit. It is blindingly clear that we should rejoin ASAP.

Any discussion of UK prospects after this war must reconsider Brexit. UK has been weak, isolated, indecisive and too slow. Churchill had no such problem, and wanted union with France in 1940. Postwar he wanted a sort of United States of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/16806981f3

Churchill knew we would be stronger together.

Report

Boris Johnson published that the success of the covid vaccination scheme was due to being out of the EU. However this is another piece of false facts. Our response would have been the same either in or out of the EU The EU did not influence the response of its member countries. looking at your data that is about the only benefit you quoted and should be discounted.

Agreed to early to call another referendum, wait and the negatives of being out will increase and further influence opinion.Report

This poll offers the exact opposite result of the recent YouGov poll, which gave an outcome of 55/45% in favour of joining the EU.

Why such a big ten point discrepancy, within days of each other?

Who commissioned the Redfield Wilton Strategies research? Report

I have always been troubled by the category “those Remain voters who would vote to rejoin”.

I voted Remain and, following the referendum, did as much as I could to promote a confirmatory referendum in the hope that UK would reverse its initial Brexit decision, revoke Article 50 and choose to remain a member of the EU. When the Withdrawal Agreement was finally passed by Parliament, I accepted that it was game over and UK was on an irreversible course to leave the EU.

Since then, I have considered the question “Would you vote to rejoin the EU?” as a meaningless and purely hypothetical one; a question that I am unlikely ever to be asked in a concrete and meaningful context in my lifetime (I am 73).

The comment: “This suggests that […] many of the Remain supporters who now say that the UK should stay out are doing so despite still taking a relatively negative view of the consequences – and that their support for staying out represents more of an acceptance of a fait accompli than an endorsement of the decision to leave.”

is an accurate reflection of my own position. This in no way diminishes my view that UK’s leaving the EU was a massive mistake on many fronts.

Please, stop using the hollow and misleading category “those Remain voters who would vote to rejoin.”Report