Following yesterday’s second anniversary of the 2019 general election, today sees the launch of another book on that contest. This is a volume on ‘Political Communication’ in the election. It uniquely brings together the perspectives and insights of academics, pollsters, journalists and campaigners on the interplay during the course of the campaign between party strategy, media coverage and the findings of the polls. It is the latest in a series of such volumes that has graced every election since 1979.

Opinion polls are, of course, readily criticised when they are thought to have got it wrong. However, anticipating the outcome with a high degree of accuracy is not the only function of polls at an election. They should also help us uncover the forces and motivations that lie behind the decisions of voters, and thus enable us to analyse the successes and failures of the parties’ strategies.

The 2019 election was, of course, triggered in an attempt to resolve the parliamentary stalemate over Brexit that had prevailed during the course of the previous twelve months. So, an obvious question to ask about that contest is, ‘What do the polls tell us about the role, if any, that Brexit played in shaping the outcome of the election?’ Did voters respond to the call to express their views about Brexit? And, given that two years have now elapsed, what do they tell us about the impact that it is having now?

The remarkable electoral turbulence that preceded the 2019 general election is often now forgotten. It was manifest above all in the outcome of the European Parliament election in May, when the Brexit Party came first and the Liberal Democrats second. Britain’s traditional two-party system appeared to be under greater threat than ever before.

Brexit played a crucial role in that turbulence. In the polls conducted in the run-up to that election, the Brexit Party stood on average at 36% among those who voted Leave in 2016 but at just 1% among those who supported Leave. Meanwhile, the Liberal Democrats enjoyed the support of 23% of Remain supporters, but just 5% of those who backed Leave.

These figures suggested that many voters in an apparently polarised electorate were willing to leave aside traditional party loyalties in order to express their views about Brexit. But at this stage, the consequence was that both Remainers and Leavers were divided in their party loyalties. The former were divided between Labour and the Liberal Democrats, the latter between the Conservatives and the Brexit Party. If a general election had been held in the summer of 2019 it might, given the first-past-the-post electoral system, well have been a highly unpredictable lottery.

However, Boris Johnson’s success in winning the contest that did take place during the summer – for the leadership of the Conservative Party – transformed the balance of party preferences on the Leave side. Now that the party was led by someone closely associated with the Leave campaign, support for the Conservatives increased in the polls by 18 points among Leave voters, while that for the Brexit Party fell by 14 points. Backing for the Conservatives among Leavers then edged up another three points (and Brexit Party support fell by two points) when in October the Prime Minister secured a revised version of the EU Withdrawal Treaty.

Remain voters, in contrast, continued to be evenly divided between Labour and the Liberal Democrats. Indeed, the Remain vote did not begin to consolidate at all until the 2019 election was called. Although the Liberal Democrats had played a vital role in triggering the contest, the moment it was announced their support began to fall away, and Labour emerged as clearly the most popular choice of Remain voters. By the time the final polls were published, Labour support was up on its pre-election standing by 12 points among Remain voters, while the Liberal Democrats were down by 12 points. Both Remainers and Leavers were still voting very differently from each other, but, on both sides, they were now inclined to express their views via the traditional two-party system rather than by backing the challengers to that system that had done so well in May.

Yet the consolidation of Remain support behind Labour did little to help the party narrow the overall lead that the Conservatives enjoyed in the polls – because whatever progress Labour made during the campaign among Remain supporters was matched by further consolidation of the Leave vote behind the Conservatives. Support for the Conservatives rose during the campaign by a further 14 points, while backing for the Brexit Party collapsed by 17 points – not least, of course, on account of Nigel Farage’s decision to stand down his candidates in seats that the Conservatives were defending.

In the event, according to two large polls conducted immediately after the election, one by Lord Ashcroft and one by YouGov, as many as 78% of those who voted Leave in 2016 backed either the Conservatives or the Brexit Party, while 80% of those who had backed Remain supported one of the parties that were willing to hold another referendum. But whereas the consolidation of the Leave vote meant that the Conservatives secured the support of 74% of Leave voters, the continued relative fragmentation of the Remain vote meant that Labour only had the support of a little under half (48%) of Remain voters.

It is this contrast between the partisan division among Remain voters and the relative unity of Leave supporters that explains why the election produced a pro-Brexit government with a majority of eighty even though rather more votes (52%) were cast for parties that were willing to hold a second referendum than were cast for parties in favour of the implementation of Brexit (47%). These two tallies, incidentally, match the level of support for Remain and Leave in the polls at the time.

But why was the Leave vote much more united than Remain support? We already have one clue from the fact that the consolidation of the Leave vote began as soon as Boris Johnson became Prime Minister – the relative popularity of the leaders. On average in the polls that Opinium conducted during the election campaign, Leave voters approved of the job that Boris Johnson was doing as Prime Minister by 64% to 20%. In contrast, Remain supporters were divided in their evaluations of both Jeremy Corbyn (34% approved, 36% disapproved) and Jo Swinson (37% approved, 29% disapproved).

Meanwhile, although Leave voters were largely convinced of the competence of the Conservatives – for example, according to Deltapoll, 71% thought the Conservatives were best able to handle the economy, while only 14% reckoned Labour were – Remain voters did not feel as confident about Labour – only 48% thought the party was best able to deal with the economy while as many as 32% named the Conservatives.

In particular, these considerations, together with some doubts about Labour’s policies, could have helped ensure that if Remain voters who had backed the Conservatives in 2017 did defect in 2019 they did so for the most part to the Liberal Democrats rather than Labour. In contrast those who voted Labour in 2017 and Leave in 2016 seemed comfortable with the policies, leadership, and competence of the Conservatives, and thus this was the destination of choice among those Labour Leavers who defected.

Most voters did then largely reflect their views on Brexit in how they voted in 2019. Yet at the same time considerations of leadership and competence played a vital role in shaping how in a multi-party election voters expressed their views about whether or not to proceed with Brexit. It was this that enabled Boris Johnson to deliver Brexit.

But to what extent is the issue of Brexit still shaping voters’ views two years on? Is it the case that now that Brexit has been done, the relationship between voters’ attitudes towards Brexit and their party preference has weakened significantly – or is it still very much apparent in the findings of the polls?

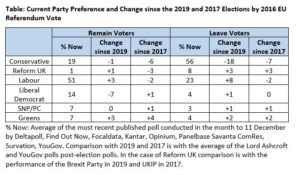

The table below shows the average level of support for the parties among Remain and Leave voters in polls conducted over the last month. It also shows how their level of support compares with what they obtained in 2019 and 2017.

Two key patterns emerge.

First, the level of support for the Conservatives has fallen heavily since 2019. The principal beneficiaries have been Labour, though Reform UK have also picked up some support. The consolidation of the Leave vote behind the Conservatives has been significantly eroded. Meanwhile, although the Liberal Democrats have lost ground among Remain voters, Labour have made only modest progress among this group. The party preferences of Remain voters continue to be fragmented.

Second, although this means the relationship between how people vote in 2016 and party preference is weaker now than it was in 2019, it is still as strong as it was in 2017 (when it was much stronger than in 2015). As compared with that occasion, the rises and falls in party support are for the most part remarkably similar among Remainers and Leavers. As a result, support for Labour among Remain voters is still a little more than twice that among Leave voters, while backing for the Conservatives is nearly three times that among Remain supporters. The Brexit divide may not play as dominant a role at the next election as it did in 2019, but on present form it is still set to have a substantial impact on the shape of party support next time around.

Political Communication in Britain: Campaigning, Media and Polling in the 2019 Election, edited by Dominic Wring, Roger Mortimore and Simon Atkinson, is published by Palgrave Macmillan. This blog draws on the author’s contribution to the book.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.