For all the apparent differences between them, both Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn have shared one objective in common as they have developed and advocated their respective positions on Brexit. Both have been pursuing a compromise.

The Prime Minister has been explicit about this. Throughout the debate on the deal she negotiated with the EU, she has repeatedly admitted that what she brought back was a compromise between what London wanted and what Brussels was prepared to offer, and between respecting the result of the referendum (in deference to the views of Leave voters) and protecting the nation’s economy and security (thereby addressing some of the concerns of Remain supporters).

In Jeremy Corbyn’s case, the compromise is implicit but still apparent. The Labour leader has argued that his party’s policy of accepting Brexit but seeking a customs union and a close relationship with the single market would ‘bring the country together’ because it would give both the 17.4 million who voted Leave and the 16.1 million who backed Remain at least some of what they want. So, in practice he too has been trying to appeal across the Brexit divide.

Following the rejection of the Prime Minister’s deal last week by the House of Commons, the government has been engaged in talks with MPs on all sides of the Brexit debate with a view to finding a possible compromise that would secure majority support in the Commons. Later today Mrs May will unveil the fruits of her discussions and propose a motion on her next steps that is due to be debated and voted upon next week.

Others too have also been in search of common ground in the wake of an apparent parliamentary impasse. The most notable effort has come from a group of MPs led by the Conservative MP, Nick Boles, who have suggested that the way out of the apparent deadlock would be for the UK to seek a future relationship with the EU similar to that currently enjoyed by Norway. This group have suggested they might attempt to amend the government’s motion so that MPs could, as one possibility, pass legislation that paved the way to a softer Brexit (and ruled out leaving without a deal) even if the government remained opposed to the idea.

However, the fate of Theresa May’s deal, not only in the House of Commons last week but also in the court of public opinion, should give those engaged in this search for a compromise pause for thought. The decision by MPs to reject the deal reflected the mood of the public, amongst whom, according to YouGov, opponents of the deal outnumbered supporters by two to one. Moreover, both Remainers and Leavers were largely of one mind in rejecting the deal. On average, those who voted Remain in 2016 did so by 54% to 22%, while those who backed Leave also did so by 48% to 30%. Rather than generating a consensus, Mrs May’s deal ended up looking friendless.

Could a different compromise avoid a similar fate? During the last couple of months there have been various attempts made by the pollsters, including in polls commissioned by organisations advocating on one side or other of the Brexit debate, to test the popularity of the various options that have been suggested during the course of the debate. However, asking voters to give a verdict on maybe as many as half a dozen different options, some of which may not be familiar to them and may therefore require some explanation, is by no means an easy task. Meanwhile the range and the detail of the options presented to respondents have inevitably varied from one poll to another, as has the way in which they have been invited to express their views.

Nevertheless, a clear theme emerges from these exercises – finding a Brexit compromise that is popular with voters and bridges the Brexit divide is at serious risk of proving a fruitless exercise.

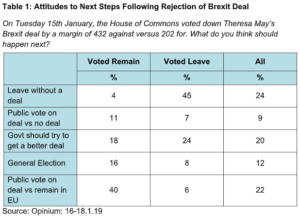

Consider, first of all, the pattern of responses to a question fielded by Opinium, as detailed in Table 1. This focuses on the procedural steps that might be taken in the wake of the parliamentary rejection of the government’s Brexit deal ranging from leaving without a deal at one end of the spectrum, to holding a second referendum (a ‘public vote’) in which staying in the EU was an option at the other. The figures quoted here are for the most recent reading obtained shortly after the defeat of the deal, but previous readings towards a similar question about what should happen if the Commons were to vote against the deal that was fielded from September onwards uncovered much the same results.

One key pattern emerges straight away. Remain voters and Leave supporters have very different views about what should be happening in the wake of the defeat of the deal. As many as 45% of Leave supporters said they thought the next step should be for the UK to leave without a deal. In contrast, the most popular option among Remain supporters, backed by 40%, was to hold a referendum in which remaining in the EU was an option.

Thanks to this very different pattern of preferences among Remain and Leave supporters, none of the options emerge as particularly popular overall – including what might be regarded as the more intermediate position of the government attempting to secure a better deal. That possibility was backed by just one in five.

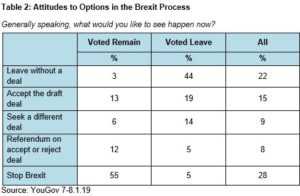

The polarisation of opinion is even more apparent in the responses to a question posed by YouGov shortly before the meaningful vote. This question was not based on the premise that the deal had been voted down, while its wording focused more on the substance of what should happen. This latter feature meant that stopping or reversing Brexit was one of the answer options – and it was backed by as many as 55% of Remain voters. As a result, support for another referendum was much lower than in Opinium’s poll. Nevertheless, the further 12% of Remain supporters who did select it meant that no less than two-thirds of Remain supporters either backed a reversal of Brexit or a procedure that might lead to the same outcome. There was little sign here of potential interest in a Brexit compromise.

At 44%, support among Leave voters for leaving without a deal, was rather less in this poll than in the poll conducted by Opinium (see Table 1). This probably reflected the fact that, with accepting Mrs May’s deal included as one of the options, nearly one in five Leave supporters were willing to indicate a preference for that possibility. Even so, just 15% of all voters chose Mrs May’s compromise, while less than one in ten of all respondents (9%) backed seeking a different deal (which might or might not have been a compromise).

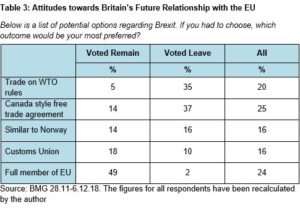

Still, neither of these questions tell us much about attitudes to some of the specific substantive alternatives to Mrs May’s deal, including those that have been canvassed in the wake of its rejection. Table 3, which comes from a poll conducted at the beginning of December by BMG Research, gives us some indication of where voters stand on the spectrum of substantive possibilities, including above all the suggestion that a softer Brexit than that envisaged by the Prime Minister might prove a more popular compromise than Mrs May’s deal proved to be.

Despite the inclusion of such possibilities as having a similar relationship with the EU as Norway or remaining in the EU customs union, the apparent reluctance of many Remain voters to embrace any form of Brexit is repeated. Almost a half of Remain voters (49%) say that the UK should remain a full member of the EU. Meanwhile, among those who supported Leave, as many as 72% either pick leaving without a deal (and trading under WTO rules) or a Canada-style free trade agreement – a proposal popular with pro-Brexit Conservative MPs but not with many on the Remain side of the argument, or, as the Table shows, with Remain voters.

As a result, only around a third of Remain voters (32%) and a quarter of Leave supporters (26%) pick the two soft Brexit ‘compromise’ options of either having a similar relationship with the EU as Norway, or (unlike Norway) being part of the customs union. These two options also have a degree of popularity among those who did not vote in June 2016, but even so, they still only command the support of around one in three of all respondents. In contrast, as many as 45% back the Leave-inspired positions of either leaving without a deal or trading under WTO rules – while, once again, no single option has widespread public support.

The relative lack of support for some of the softer Brexit options that have been proposed as a compromise has been confirmed when voters have been presented with a much simpler choice of leaving without a deal, staying in the EU, or pursuing one or other ‘compromise’ option. Each time the soft Brexit option has been the third most popular choice.

For example, earlier this month Survation reported that just 24% would prefer a Norway-style relationship with the EU, whereas 32% backed leaving without a deal and 35% favoured staying in the EU.. Meanwhile, when last week YouGov asked voters to choose between a Norway-plus arrangement, and, again, leaving without a deal and remaining in the EU, just 8% selected the Norway option. In the same poll, just 7% picked staying in the customs union when this option was pitted against leaving without a deal and remaining.

These results are, in truth, remarkably redolent of what happened when voters were asked to choose between Mrs May’s deal and the two more straightforward options or leaving forthwith or remaining – and indeed too when they were asked in a similar vein about the Chequers agreement.

Still, it might be felt that looking at how many people pick a compromise option as their first choice underestimates the potential ability of any such solution to bring Remain and Leave voters together. It might be thought better to look at what happens when voters are simply asked whether they support or oppose each option in turn. Although a compromise option may not be many people’s first choice, perhaps many might at least find it acceptable.

Two recent polls have asked people about some of the possible options in that way. However, they provide little support for idea that any of them is likely to be capable of crossing the Brexit divide.

Earlier this month BMG asked voters whether they supported a number of options, including – as a stop-gap measure at least – a Norway-style relationship. This proved relatively popular among Remain voters, 60% of whom said they supported the idea, with just 23% opposed. However, Leave supporters were on balance strongly opposed to the idea, with just 28% in favour and 55% opposed.

Meanwhile, YouGov have asked whether staying in the single market and the customs union would be a ‘good outcome’ a ‘bad outcome’, or an ‘acceptable compromise’. Among Remain voters 36% said that it would be a good outcome, while another 32% indicated that it would be an acceptable compromise. However, among Leave voters the equivalent figures were just 15% and 19% respectively.

We will see in the next week or so, whether anyone has found a compromise that can command the support of a majority of MPs, including perhaps an amended version of Mrs May’s deal. But anyone who hopes that such a compromise might serve to heal the divisions between Remainers and Leavers in the Brexit debate would be unwise to set their expectations too high. Voters’ reactions to previous attempts to find a compromise suggests that any such proposal is at risk of being rejected by both sides in the Brexit debate – and on the evidence so far it appears that the same fate could well befall any of the softer Brexit compromises that have been canvassed to date.

Politicians are used to seeking out the ‘centre ground’ of British politics because that is where they believe (or are told) most voters are to be found. However, in the case of the Brexit debate that ground appears to be quite thinly populated. Perhaps the piece of political folk wisdom that it would be more appropriate to bear in mind in the next few weeks is that ‘to govern is to choose’?

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

There is an inherent problem in trying to calculate the comprise or middle ground in that there is the danger of splitting one side of the vote over the other. This is where the remainer or the leaver can bias the poll even though they might have the best intentions in mind. For example if a three option poll is raised with options to remain, leave with plan A or leave with plan B is likely to split the leave vote and therefore to raise the remain side of the options. What I personally get from these polls is that one side is far more reluctant to compromise. What is critical in the wider picture of democracy is to remove options to remain and or second referendum. Democracy is not an excuse to argue for a re-vote on the grounds that the original result is unpopular with the minority. That will lead to the destruction of the the value of voting in the first place. Do voters in General Elections then ask for a second or third vote on the grounds they don’t like the result? The decision, regardless of the fact both sides failed to put forward any ‘grey’ options, was made based on the black and white options presented. What we need to do is stop going back over old ground and concentrate on the numerous options open to the UK on leaving the EU. Remain is not an option regardless of which way we personally voted. Remove the option to remain and the country will start to pull together to get the best deal rather than expending energy continuing to flog the dead horseReport

There is a limit to how much you can find out about people’s preferences when you only ask people to give their first preference among multiple options. It may be difficult to get the public to accept preferential voting for a multi-option referendum – I hope we get the opportunity to find out! – but that’s no reason for opinion polls not to ask for people’s order of preference among a list of options: the few opinion polls that have done this have been very interesting, the most recent I’ve seen being by Yougov in early December. At that point, first preferences were Remain 46%, with Deal and No Deal tied on 27%; but in the 2-way comparisons it was Remain and Deal that were neck-and-neck, with either of them beating No Deal by some margin.Report

Referenda are not decision making instruments under UK rules and the Brexit one is legally advisory. It was only that MPs promised in some majority that results would be implemented, which gives it a moral obligation.

Commentators have pointed out that it was a fatal flaw to confuse two levels of democracy. In the end, however, it is the legal obligation of MPs to decide and put themselves to the vote of their constituents at the next General Election. At this point MPs have to weigh the promise made against the good of the country. If the latter is threatened by current circumstance, i.e. a hard Brexit, they should renege on their promise and try to explain the decision to the electorate.

The divisions in the electorate might suggest we are looking forward to a number of changes in the next House of Commons. Sacrificing the country in the name of one or the other extreme outcome, should not be an option.Report

Answering comment re referendum law. – No parliament can be held to the decisions of a previous parliament – Mrs May had an electin it is now a “new” parliament. Ergo it can dismiss the previous obligation and do its duty to the nation. It also has a higher duty to look to the interests of the nation. That is theory, in practice the last two years have been about the survival of the Conservative Party – nothing to do with Brexit. It is only now that there is any attempt to arrive at a concensus as to how to leave the EU , Some issues – like what to do about EU citizens in UK and Uk citizens in EU could have and should have been settled in week one. The rest by inter party negotiations and free votes. NB still doesn’t answer my query about knowledge & consequences by voters/citizens.Report

The problem is the same as it was in early 2016. Brexit is a binary decision to complex problem. Mrs May is seeking a compromise ‘middle way’ but it does not exist. We are either OUT as in WTO or Canada FTA terms, with all the damage that will do to Ireland and our own economy, or we are IN as in Norway ++ or full membership and either following or shaping the rules. There is a huge difference between the two extreme positions. The EU are never going to allow cherry picking on the scale we want.

In 2016 politicians tried to convince us we could have the best of both worlds. We can’t, and it’s now time to choose which world we actually want.

This is why ultimately it must go to a people’s vote to confirm the original decision, accepting the economic costs, or to remain a member. Report

Everyone seems totally confused and inifinately divided as regards what solution to take and even thought you mention the alternatives. What percentage of the people asked actually know what is entailed in each option – personally I have no idea what either the Norway or Canada options mean- except that the Canada deal took 9 years to ratify. Perhaps you could resurvey the level of understanding of all options – that would make interesting reading. Whilst you are at it why not suggest that MP’s do what we elect them for – obey their conscience and vote for what they as individuals think is the right solution, rather than party political maouvering to gain some advantage over each other.Report

“. . . why not suggest that MP’s do what we elect them for – obey their conscience and vote for what they as individuals think is the right solution . . .”. Normally that’s what MPs ought to do, but in this case they passed a law asking the electorate to make the decision in a referendum. So now the duty of the MPs is to vote to implement the expressed wish of the electorate, not to place their personal opinions above that expressed wish. By referring the decision to the people they introduced an anomaly into the usual arrangements for the sovereignty of Parliament. The sovereignty of the people trumps the sovereignty of Parliament – at least it ought to. But Remainer MPs in their arrogance think their opinions are worth more than those of the electorate, unfortunately.Report

Sorry, this is not legally true. The House of Commons Library briefing, published when Parliament was debating the referendum legislation, is entirely clear that the referendum would be advisory to Parliament, who would make the final decision. The government of the day then published a leaflet promising that the referendum would be a mandate – which in UK law it cannot be. Another example of the irresponsible casual behaviour of Cameron & co.Report

Extremely helpful analysis of the polling, thank you J.C. You show that there’s little point in going through the options to see whether there’s any that commands a majority among MPs — none does. There’s no point either in trying to determine what’s best liked by MPs, because it might also be the worst liked. They really need a mechanism (do’you agree?) to determine what’s most strongly dispreferred, second most strongly, .. so as to see which is least disliked, and thus might be compromised on. Of course the House of Commons has no such mechanism.Report

1. Preferential voting should have been explored in the polls.

2. It is not surprising that Mrs May’s deal is not liked. It – and indeed any kind of compromise – is like King Solomon’s proposed solution. It pleases neither ‘mother’.Report

Re-read your Bible, on “The wisdom of Solomon”. Each mother was asked to say if the child should be given to the other woman, or be cut in half, so they would have an equal share. Solomon knew that the real mother would want her child to live, even if she could not have it herself. The mother whose real child had died (smothered in an accident I seem to remember), wanted a sort of perverted revenge, having inadvertently killed her own child she wanted the real mother of the surving child to suffer as she had. It’s not entirely like Brexit, because both sides want to punish the other (at least in most HYSes on the subject). Unfortunately it is not equivalent to Solomon, because both sides truly believe their option is best for the UK. and say they are not lying, or at least deny they have been lied to, despite a lot of evidence to the contrary.Report