Ever since the EU withdrawal deal was published in November, Mrs May has been struggling to persuade MPs to back it. On Tuesday, we should learn whether she has eventually managed to win them over or not. Her attempts to do so have not been helped by the fact that voters have also proved to be doubtful about the deal. YouGov, for example, have consistently found that only around 25% back the deal, while some 45% or so are opposed, with around 30% saying they don’t know whether they support the deal or not.

It is not immediately obvious that the content of the deal should have received such an unenthusiastic response. Research on attitudes to Brexit suggests that most people want to continue to trade freely with the EU but also want the UK to have much more control over immigration. Under the Northern Ireland backstop that has been the subject of much criticism from MPs, Britain would continue to trade with the EU under single market rules while still being able to introduce controls on EU migration. This aspect of the draft Withdrawal Treaty thus apparently meets the public’s, and especially Leave voters’, main requirements. Meanwhile, the accompanying Political Declaration offers the prospect, at least, of a close trading relationship in years to come, while recognising that the UK does not wish to maintain freedom of movement.

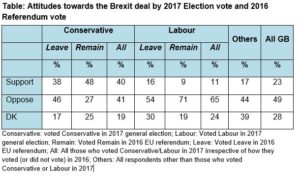

So how then can we account for the unpopularity of the Brexit deal? We try to answer this question using data from a survey of 1675 adults conducted by YouGov on 18th-19thDecember 2018 for the ESRC-funded Party Members Project. In this particular exercise, 23% said that they supported the deal, 49% that they were opposed, while 28% indicated that they didn’t know.

Perhaps the most immediately obvious explanation for the deal’s unpopularity is that it is strongly opposed by those who would prefer to remain in the EU. Remain voters are, indeed, unhappy with the deal – but not much more so than Leave supporters. In our survey, only 21% of those who voted Remain in 2016 said that they support the deal, while 56% indicated that they were opposed. Equally, however, only 29% of Leave supporters stated that they supported the deal, while 48% were opposed.

Similarly, only 5% of all voters say they would be “pleased” or “delighted” if the deal passed, while a further 13% would be “relieved”. At 9% and 14% respectively, the corresponding numbers among Leave voters are only marginally better.

Perhaps it is all a question of party politics? Maybe support for the deal is so low because it is being proposed by a Conservative government, and that consequently supporters of other parties are reluctant to accept it. Indeed, as the table below shows, support for the deal stands at just 11% among those who voted Labour in 2017, and is similarly low among Liberal Democrats and voters for other parties that support Remain such as the SNP and the Greens. Yet even among Conservative voters only two-fifths (40%) say they back it. The only group of voters among whom supporters of the deal outnumber opponents (by 48% to 27%) are those Conservatives who voted Remain in 2016, almost half of whom support the deal.

Perhaps these Conservative Remainers are more willing than their Leave counterparts to regard the deal as an acceptable compromise, in line with one of the arguments the government has been deploying in an attempt to win over support. Maybe, too, they are more supportive of Theresa May and thus are willing to follow her lead. Certainly, among those Conservative voters who think Mrs May is doing “well” as Prime Minister, as many as 58% support the deal, compared with just 14% among those who think she is doing “badly”. Maybe this difference, however, arises because those who like the deal are more likely to approve of Mrs May rather than vice-versa. In any event, Conservative Remainers are not particularly likely to think that the Prime Minster is performing well and so the pattern does not explain why they are more likely than Tory Leavers to support the deal.

Apart from presenting the deal as a compromise that contains something for both Remainers and Leavers, the Prime Minister’s other key tactic has been to warn of the consequences of rejecting the deal. First, she has been telling MPs that it might result in a “damaging” no-deal Brexit. Second, she and her ministers have argued that it might mean that Brexit does not happen at all.

Neither argument seems to have much traction in persuading voters to back the deal. Only 35% of all voters believe warnings that “Britain leaving the European Union without agreeing a deal could cause severe short term disruption, such as shortages of food and medicines.” True, those warnings are widely believed by supporters of parties other than the Conservatives, but as we have already seen they are least likely to support the deal! But even among Conservative voters, those who believe the warnings are realistic are only seven points more likely to support the deal than those who think the warnings exaggerated. It is a similar story when voters are asked about the medium and long-term economic consequences of leaving the EU without a deal. Those Conservatives who think that leaving without a deal would have a negative impact on the economy are only six points more likely than those who think it will have a positive effect to support what the Prime Minister has come up with.

So far as Brexit not happening at all is concerned, naturally Remain voters would be happy if “Britain ended up having a new referendum and voting to remain in the EU after all”, while some two-thirds of Leave voters, and a larger share of Conservative Leave voters, would feel “betrayed” or “angry”. However, these particularly staunch Tory Leavers are no more likely to support the deal than those Tory Leavers who are more relaxed about the prospect of Remain winning another referendum.

Perhaps, then, the reason for the deal’s unpopularity with the public is to be found (as is the case with many MPs) in attitudes towards the Northern Ireland backstop. Indeed, only 18% think that it “makes sense and should be part of the deal”, while even fewer Conservative voters (15%) and Leave supporters (11%) think that is the case. Conservative voters are more likely instead to take the view that the backstop is “a bad idea but it’s a price worth paying to secure a deal.” However, support for the deal among this latter group (72%) is actually slightly higherthan it is among those Conservatives who believe the deal makes sense (65%). So, disapproval of the backstop per sedoes not appear to be an essential barrier to supporting the deal.

Perhaps, then, we should step back and remind ourselves that, despite the intensity of the debate at Westminster, many voters still do not know whether they support the deal or not. Maybe this is indicative of a wider problem for the Prime Minister, namely that voters for whom politics is not a passion find the debate about the deal rather too complicated – and thus take the view that perhaps the deal itself must be too complicated as well?

As we might expect, people who pay more attention to politics are, indeed, far more likely to have an opinion on the deal. Only 8% of this group do not have a view compared with 53% of those who pay relatively little attention. However, sadly for Theresa May, they are also more likely to oppose the deal than they are to support it. True, among her own voters the balance of support and opposition is much the same among those who pay more attention to politics as it is among those who pay less attention. But among Labour voters, those who pay more attention to politics are on balance much more likely to oppose the government’s deal, perhaps because they are more aware that their party is against the deal and take their cue accordingly. In any event, to know the deal is not necessarily to love it.

This analysis makes rather grim reading for the government. The overall level of support for the deal is relatively low, and there is little sign that the main arguments the government has deployed have proved persuasive with many voters, not least among those who voted Leave. Moreover, in so far as those who have not yet formed an opinion might eventually do so, there is no reason to believe that they will necessarily swing in behind the deal – indeed, in the case of Labour voters the opposite would seem more likely. Meanwhile, given that two-thirds of Labour voters are already opposed to the deal, there is seemingly little immediate incentive for Labour MPs to respond to attempts by the government to try to win them over. It looks as though Mrs May has to hope that MPs are not taking too much notice of the polls when they vote on the deal on Tuesday.

This blog is co-authored by Tim Bale, Professor of Politics at Queen Mary University, London, and Co-Director of the Party Members Project. Both authors are grateful to Alan Renwick for helpful comments on a previous version.

By Stephen Fisher

Stephen Fisher is Associate Professor of Political Sociology at Trinity College, Oxford

Brexit is a failure from fishing trade immigration DEATH in the channel .sewage dumped in the channel,prices,our reputation abroad,spaces in supermarkets,UK in danger of being split up.Whats good about it?Report

If remaining in the EU is so much better than Brexit then why did the country force a refetendum in the first place? Obviously because the country generally was not happy with the way we were being governed by EU bereaucrats. By remaining in the EU we are going back to what we were trying to get away from. Report