The question of whether or not there should be a second referendum has been one of the hottest topics in the Brexit debate during the summer. In part, the debate has been stimulated by the relatively adverse reaction with which the Chequers Agreement was greeted, a reaction that led some, such as the former Conservative minister, Justine Greening, to advocate the idea of a three-way ballot between no deal, Chequers and remaining. That adverse reaction certainly helped fuel speculation more generally about the difficulties seemingly facing the government, first, in reaching an agreement with the EU and, second, in securing parliamentary approval for the outcome of the negotiations – and the possibility that another referendum might play a role in resolving any resulting impasse. At the same time, the discussion has been stimulated by the efforts of the high profile pro-second referendum Best for Britain and People’s Vote campaigns, who have managed to secure considerable publicity during the relative quietude of the parliamentary recess, and who are attempting to persuade the Labour Party in particular to support a second ballot.

As part of their campaigning, those two organisations have been keen to give the impression that not only is there majority support for a second referendum, but also that this support has been growing. There has certainly been plenty of polling on the subject in recent months, including not least polling commissioned by these campaigning organisations themselves. But how much support is there now for a second referendum, and is there any sign that it has grown, not least perhaps in the wake of the Chequers Agreement?

In our analysis of previous polling on attitudes towards holding a second referendum, we have noted two key features. First, the wording of the question matters; voters are less likely to endorse the idea if asked whether there should be another ‘referendum’ than if they are asked whether the ‘public’ should be able to vote. Second, the form of the referendum matters; Leave voters are, unsurprisingly, rather warmer to the idea of a referendum in which the choice is between whatever deal the government has negotiated and no deal than they are towards one where the choice is between a deal and remaining in the EU.

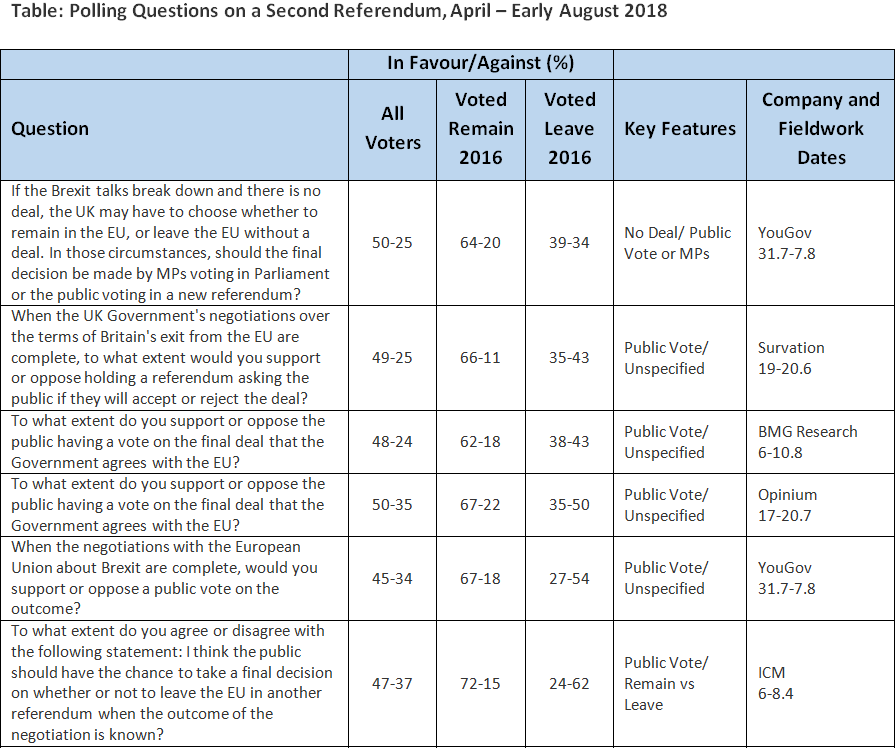

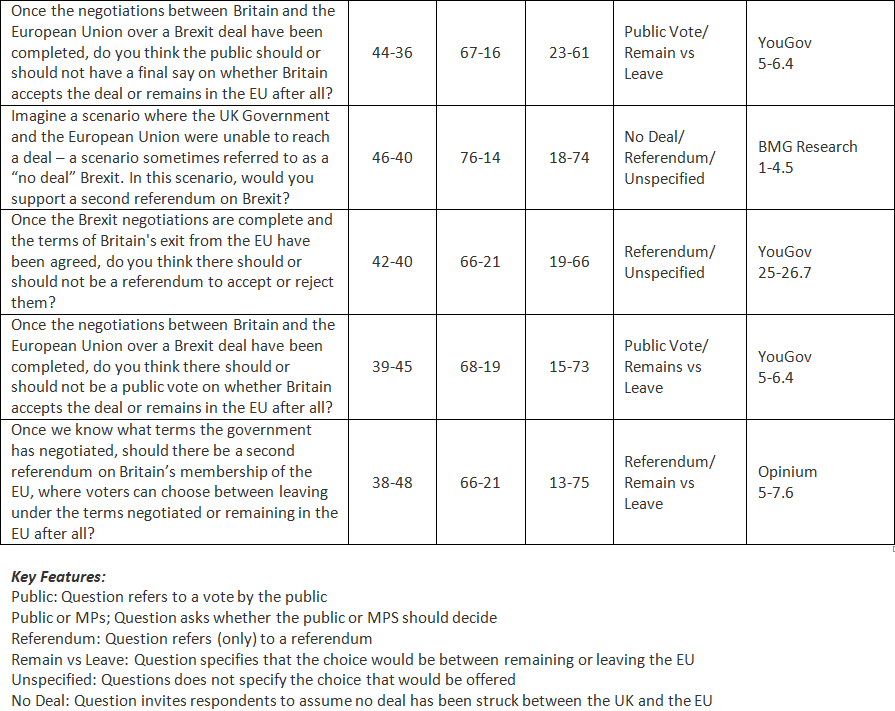

Meanwhile, one striking feature of the most recent recent polling on the issue is that many very differently worded questions have been asked. Leaving aside questions about a multi-option ballot (on which see here and here), all in all, no less than eleven differently worded questions about a second referendum have been included on published polls since the beginning of April. And as we might anticipate these have elicited rather different patterns of response, from which proponents and opponents of the idea have been able to cherry pick as they see fit. Meanwhile, many of the questions have only been included on one poll, which means that ascertaining whether or not attitudes have changed over time is, despite the plethora of polling on the subject, rather more difficult than might have been hoped.

The table at the bottom of this blog details the variety of polling that has taken place. It shows, first, the exact wording of each question that has been asked, the most recent level of support and opposition recorded in response to that question among voters as a whole, and, then, the level of support and opposition separately for those who voted Remain in 2016 and those who backed Leave. The questions are listed in order of the extent to which voters as a whole expressed support for rather than opposition to the idea. Meanwhile on the right-hand side of the table we identify some of the key features of the wording of each question, and provide brief details of the polling company and the dates of the fieldwork.

One point immediately stands out. Most of these questions have found more people in favour of a second referendum than opposed. But the balance of opinion has varied considerably. In those polls listed at the top of the table twice as many people expressed support for a second referendum as said they were against. In those at the bottom of the table, opponents outnumbered proponents by ten points. In between are a number of polls that exhibit a modest excess of supporters over opponents, while in most instances, although more numerous than opponents, the proportion actually expressing support is rather less than half. (Invariably, many respondents to these polls choose the mid-point ‘neither’ option, if available, or else say that they don’t know.)

We can, however, make sense of much of the variation by reminding ourselves of the two key lessons of previous polling on this subject. First, only three of the questions refer to holding another referendum as opposed to some kind of vote of the ‘public’. These three polls account for three of the four entries at the bottom of our table. Second, only four polls specify what the options would be on the ballot paper, in each case indicating that the choice would be between Leave and Remain. Two of these polls appear at the bottom of our table, while the other two have among the lowest levels of support among those polls that refer to a vote by the ‘public’.

In short, polls that ask people whether the ‘public’ should have a vote usually record a higher level of support than those that just ask whether there should be another referendum. Equally, polls that do not specify what the alternative would be to endorsing whatever deal is reached tend to secure higher levels of support than those that indicate that the choice would be between leaving (on whatever terms have been agreed) and remaining.

But why do these patterns arise? We secure a valuable clue if we look separately at the responses of those who voted Remain in 2016 and those who supported Leave. This reveals a striking contrast. The balance of response among Remain voters is much the same irrespective of the question asked, while there is little or no discernible pattern to the variation that does exists (though perhaps we might not be surprised that support for another referendum is particularly high among Remain supporters when respondents are asked what should happen in the event that there is no deal at all). It looks as though we can say with a considerable degree of confidence that around two-thirds of Remain voters are in favour of another ballot while only around one in six are opposed. Most likely, many of the two-thirds of Remain supporters that respond positively to polling questions on the subject simply assume that remaining would be one of the options on the ballot, irrespective of the precise wording that is used.

The picture among Leave voters, however, is very different. They are more likely to back another ballot when it is presented as a vote by the ‘public’ than as a ‘referendum’ and less likely to support the idea if it is made clear that the choice would be between remaining and leaving. The latter point is, perhaps, not surprising. After all, most Leave voters do not think that the original majority vote to Leave should now be questioned or overturned. The former pattern, most likely, reflects the populist outlook of some Leave supporters that means that they warm to the idea of power being placed in the hands of the people rather than an elite. Given this outlook, it is perhaps not surprising that the one and only question where more Leave voters expressed support than opposition was one where respondents were asked whether, in the event of there being no deal, the decision about what to do should be made by MPs or the public. After all, as other recent polling for The People’s Vote has shown, few Leave voters trust MPs to make the right decisions about Brexit.

So, whether or not there is majority support (or more accurately, a plurality of support) for a second referendum is less clear than might be imagined from an initial, quick glance at the headline polling results. Certainly, if we are to use polling to evaluate the level of support for the kind of referendum being promoted by The People’s Vote, that is, one in which the alternative to accepting whatever deal had been agreed would be to remain in the EU, it would seem essential to refer only to those polls that make clear that the choice in another ballot would be between Leave and Remain. Meanwhile, it is at least debatable as to whether it is wise to use wording that might be thought to be playing into the populist sentiment that exists among some Leave voters. Maybe if the issue does become more pressing in the autumn, opponents of Brexit would prove able to invoke such sentiment in support of another ballot. But equally, perhaps, that support might evaporate if it became clear to Leave voters that a second ballot would revisit the issue of whether Britain should leave the EU in the first place.

Nevertheless, that still leaves the question of whether support for holding a second referendum has increased, and perhaps especially so in the wake of the Chequers Agreement. Until recently, two companies, Opinium and YouGov, had been asking the same question about the issue on a reasonably regular basis. Both their questions referred to a second ballot as a ‘referendum’, and in one instance, Opinium, also made it clear that the choice would be between remaining in the EU or leaving. Both have thus hitherto found more people were opposed to a second referendum than were in favour, though both also suggested that the level of opposition had fallen to some extent at least during the previous year or so. However, unfortunately, Opinium have not asked their question since the beginning of June, which means that we have to rely heavily on a single source, YouGov, in coming to a judgement as to whether there has been a further significant shift more recently.

YouGov’s data certainly suggest that there has been at least a discernible, if modest shift. In three readings of its regular question that the company took between April and June, it found on average that while 38% were favour of the idea of another referendum, 45% were against. But in three readings taken since the Chequers Agreement, 40% have said they are in favour, almost matching the 41% who are against. Indeed, in its most recent poll that included their usual question, conducted at the end of July, YouGov found for the first time slightly more (42%) saying they were in favour than stating that they were against (40%).

But is this apparent trend corroborated by any other evidence? There is some. Just before the Chequers Agreement was reached, BMG found 44% in favour and only 27% against ‘a referendum being held asking the public whether they accept or reject the terms of the deal’. When they asked the same question again at the beginning of August, 48% said they were in favour and only 24% opposed. On the other hand, the trend has not been replicated when Opinium have asked a different question from the one they had previously been asking. This question asked respondents whether they ‘support or oppose the public having a vote on the final deal that the Government agrees with the EU’. When they asked this on two occasions in April and May Opinium found no less than 53% were in favour and only 31% opposed. But when they asked the question again in July, after the Chequers Agreement, support stood at 50% and opposition at 35%.

So, while there is some evidence that Chequers may have persuaded a few more voters of the merits of holding another ballot, we probably need more instances of the same question showing an increase in support since before the beginning of July before we can be sure that this is indeed what has happened. But in the meantime, we certainly need to remember that this is a topic on which, above all, question wording matters, and where, so far, the wording has perhaps not always conveyed clearly to respondents exactly what kind of referendum is being suggested – or advocated.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

Why in a second referendum should there be remain in EU we have already voted to leave come on get over it just have two option 1. Take deal 2. Leave without a deal Report

Labour voter all my life as were my forebears, and for the 1st time I will not vote

for the current party who have failed to support the public vote on Brexit.

Good Bye Labour you have lost a loyal subject.

Report

There should be 3 questions in a second referendum

1. Remain in the European Union and fight for change from within

2. Take the deal on the table

3. Leave with no dealReport

I was under the impression that the majority of people voted to leave the EU. We should leave totally with no deal.

Much Industry has been relocated abroad over many of the years we have been in the EU.

Did I really read that France has a 12 mile fishing limit from their coastline while Britain’s was 6 miles?

We export loads to the EU, if we are prevented, who is going to take up the slack? Are our customers there stockpiling? Why are we being panicked intentionally?

Will we rebuild our shipping with money we ‘save’ from no longer having to pay into the EU so we can use our own ships rather than EU ones to transport goods?Report

There should be three questions in another vote

1.remain in its existing detail

2. Remain but nagotiate changes

3 leave totally no deal

Report

There could be 3 questions in another referendum

1. Remain in its existing detail.

2.Remain but still nagotiate changes

3.leave totally no deal

Also ex pats to have a vote

Report

Some very interesting shenannigans with polling. It’s a good example of how you can obtain the result you want by carefully selecting the people you poll. When you see “poll” results that tell you “so many percent of Labour voters,……” this is what’s going on.

https://brexitcentral.com/beware-remainers-bearing-polls/Report

What Prof. Curtice is showing us here is that it is possible to poll the pulic’s opinion on things that cannot happen, or on which the vote of the British electorate has no weight or meaning anyway.

First, as Remain never tire of reminding us, the Referendum – I am not going to call it the “First Referendum”, because a second won’t happen – was advisory. It was not the legal basis for invoking Article 50. The legal basis for invoking Article 50 was the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017, which passed both Houses unamended, including an explicit vote of 340 to 95 to reject a “second referendum”, and received Royal Assent on 16 March 2017.

So it is that Bill that needs to be repealed, and since it passed each stage by large majorities, that isn’t going to happen without a General Election and a new Government. But it won’t be repealed in any case, no matter who wins the next GE, because “Tory rebels” are only arguing about the form of Brexit, and Labour has undertaken many times to respect the Referendum outcome.

And a repeal would not matter anyway, even if it could happen, because it would not reverse the invocation of Article 50, which happened 18 months ago, but would only leave us petitioning the EU to change its own law to allow Article 50 to be reversed, which at present it cannot, and even worse, Article 50 isn’t an isolated regulation that can easily be reversed, but part of an EU Treaty that would have to receive the unanimous consent of all the original signatories of the treaty – less the UK. Does anyone imagine that Italy, say, would consent to a change in Article 50 that would risk locking Italy into the EU in perpetuity, no matter what Italian Government they might vote for in future.

And finally, timing. It would take another two years to organize and hold another referendum in the UK, and it would take about that long to get the EU to change Article 50, and by the time that either of those can happen, we will have been out of the EU for a year and a half, and the sky will not have fallen.

So, the bottom line here is that if you ask the British person on the street a question – any question – they will give you an answer, even if its meaningless. Go out into the streets and ask people if the British voter should have a voice on who is elected President of the US, or Pope, and some people will say “Yes”.

We were asked one, very simple, question. We answered it. The Government *chose* to listen to the answer, as promised. After that, we handed the complicated implementation back to the Government, which was as understood when we voted. So let’s leave it like that. Report

Every household was told via the Government pamphlet that this was their chance to decide, that it was important they voted and crucially that the result of the referendum would be implemented. Whether the author had the authority to make that claim or not the people should have been in no doubt that their vote would count.

The amount of pro-Remain propaganda since the referendum has been unrelenting and has intensified recently so it is little surprise that some ‘fence sitters’ have been persuaded to change their vote.

Nobody ‘knows’ what sort of deal the UK might get from the EU or if there will be a deal at all. This was the case before the referendum yet people voted to Leave, I believe this shows the passion behind the Leave vote.

In the two years since the vote the EU have announced an embryo EU army and Martin Schulz and JC Juncker have been promoting ‘more’ EU, leading inexorably towards full federation. If we stay in the EU is it the same EU we decided to Leave in 2016? I doubt it, are we going to have the same rebate and opt-outs as prior to triggering Article 50? I doubt it and no-one has confirmed or denied it.

Whilst some Remainers have been vociferous in their attempts to garner public support for another referendum to overturn the result of the previous referendum a larger number of Remain voters accepted the result to Leave as valid.

The result must stand and we must Leave the EU. If we do not Leave then such a betrayal of the democratic process will not be forgiven, look forward to a surge in the number of people voting for alternatives to the usual suspects at the next General Election.Report

Democracy is a process not a “winner takes all” final showdown. That’s why we have new elections every 4 years.Report

Fraud has, already, been proven, by the Electoral Commission.

Investigations are ongoing.

Any Government with – any – integrity, would have declared the result null and void, by now.

It doesn’t matter if the fraud was on one side, or on both sides. The decision is compromised and should never have been allowed to stand.Report

The Electoral commiussion have sanctions they can apply if they think fraud took place, but they consist of imposing fines. The chances of them re-running an entire referendum are about zero.Report

The Electoral Commission have, already, levied fines, totalling £61,000, on Vote Leave and their associates BeLeave.

Now, there are claims of fraud by the Remain side.

Fraud on one side is, already, proven. If there was fraud, on both sides, it’s not a great advertisement for UK Democracy.

The future of the UK is supposed to be decided by any old fraudster?Report

I believe that the Brexit referendum is one of the greatest disaster to happen to Britain.

If the majority of the people want to remain in EU, it would be a travesty of justice not to have another referendum..

However, the government is so divided that another referendum may just cause more troubleReport

Could you be a tiny bit more explicit about what form this “disaster” is taking? I must be missing it.Report

Tell that to all the people already losing their jobs as companies/contracts/etc move to Europe. Tell that to the people who used to host the EMA. Tell that to my friend who’s wife is having to move to Europe or lose her job as her employer relocates her entire office. Tell that to anyone paying extra whenever they go on holiday due to the dropped exchange rate.Report