Much has happened in the year that has elapsed between today’s seventh anniversary of the 2016 EU referendum and the sixth anniversary a year ago. Two Prime Ministers have come and gone, one of whom is not even an MP anymore. Nicola Sturgeon has stepped down as First Minister of Scotland after as much as nine years in the post. Meanwhile, the UK economy finds itself in the grip of the worst inflationary spiral since the 1970s and facing the prospect of a record decline in living standards.

Attitudes towards Brexit have changed over the course of the year too. In the poll that it conducted for the UK in a Changing Europe last June, Redfield & Wilton Strategies reported there was now a narrow majority – of 53% to 47% – in favour of re-joining the EU. This was already a rather different picture from the one it had painted just five months earlier, when only 45% indicated they would vote to re-join, while 55% wanted to stay out. Now, however, in their latest poll Redfield & Wilton estimate that (after leaving aside those not expressing a preference) as many as 61% are in favour of re-joining the EU, while only 39% back staying out. That swing against Brexit reflects a pattern found more generally in the polls over the last year.

In this blog, we compare the results of the latest Redfield & Wilton poll with that of a year ago, with a view to identifying some of the sources of the change of mood on Brexit that has occurred.

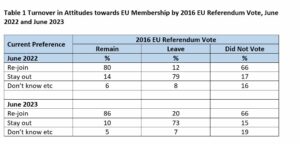

Table 1 shows how in the latest poll Remain and Leave voters, together with those who did not vote in 2016, say they would vote now if asked to choose between staying out of the EU or re-joining. The figures are then compared with those from a year ago.

Most immediately we can see that around four in five of those who participated in the 2016 ballot have not changed their mind about being inside or outside the EU. However, whereas a year ago Remain and Leave voters were more or less equally likely to stick with the choice they made in 2016, now Remain voters are thirteen points more likely to say they would vote to re-join the EU than Leave voters are to indicate that they would vote to stay out. The level of loyalty among Remain voters to the EU has increased, whereas the commitment of Leave voters to being outside the EU has faded.

Indeed, this turnaround in the level of loyalty among Remain and Leave supporters is underlined by another development. A year ago, those who said they would vote to stay out of the EU were relatively enthusiastic about participating in any second Brexit referendum. No less than 76% said that they would be ‘certain’ to vote, much higher than the equivalent figure of 63% among those who preferred to re-join the EU. Now, in contrast, those who would vote to re-join the EU are rather more likely (by 68% to 63%) to say they would be certain to vote. Redfield & Wilton’s estimates of the overall level of support for re-joining and staying out take into account survey respondents’ reported likelihood of voting, so this change is also part of the explanation for the swing in favour of re-joining the EU.

Meanwhile, we should note another feature of Table 1 – that as many as two-thirds of those who did not vote in 2016 say they would vote to re-join the EU, while only around one in six back staying out. This group comprises both those who opted not to go to the polls seven years ago, and those who were too young to do so. While here the pattern of preference is much the same now as a year ago, the number of those too young to vote in 2016, strongly opposed as they are to Brexit, is, of course, gradually increasing in size. Demographic change is also slowly generating a swing away from Brexit.

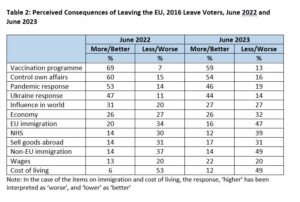

But what underlies the decision by some who voted Leave in 2016 to favour now re-joining the EU? As part of its regular polling for UK in a Changing Europe, Redfield & Wilton have been monitoring voters’ perceptions of the consequences of Brexit across a wide range of social and economic life. Table 2 shows that in some instances, Leave voters have become noticeably more critical of those consequences over the last year. In particular, there are notable changes in the balance of opinion on whether Brexit enabled aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic to be handled more effectively, on whether it changed Britain’s influence in the world and ability to control its own affairs, and on its impact on immigration, the economy, and the NHS.

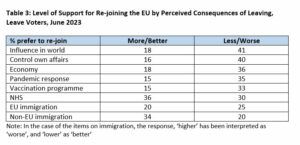

However, the extent to which changed views are associated with a change of mind on whether Britain should be inside or outside the EU differs between the subjects. Table 3 shows for those topics where attitudes have changed the most over the last year, the proportion of 2016 Leave voters who would now vote to re-join the EU broken down by whether they think Brexit has had a beneficial or deleterious impact on that issue.

On some issues where the balance of public opinion has become more critical over the last twelve months, those who think Brexit has had a deleterious impact are around twice as likely as those who take the opposite view to say that they would now prefer to be in the EU. This is true of perceptions of the impact of Brexit on Britain’s influence in the world, its ability to control its own affairs, on aspects of the pandemic and on the economy. Sovereignty/control and the economy, two of the three most important issues in the 2016 campaign, still sway Leave voters.

The same, however, cannot be said of the other key issue in the 2016 campaign, immigration. Those Leave voters who think immigration from the EU has increased in the wake of Brexit are barely any more likely than those who think it has fallen to have switched in favour of re-joining the EU. Meanwhile, it is those who think non-EU immigration has fallen who are more likely to have switched in favour of re-joining. Immigration has, it seems, lost its former ability to influence attitudes towards the EU. Reversing the swing against Brexit will require an improving economy, not rhetoric about immigration.

This blog is also posted on the UK in a Changing Europe website.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

It is a matter of on-going curiosity to me why there are (as far as I know) no polls that attempt to address the issue of W H Y so many of those eligible to vote in the 2016 Brexit referendum chose not to vote at all.

The other curiosity is the lack of thought concerning how large a proportion of those eligible but who choose not to vote it needs to be for a referendum to be regarded as invalid.

The fact is that, of those eligible to vote, ~32.0% voted Leave, ~29.7% voted Remain, and ~38.3% chose NOT TO VOTE.

W H Y ? – please ask these non-voters.

And how high would the 38.3% figure have needed to be for the referendum to be regarded as invalid?

Please ask the nation this question.

It seems that the major shift in opinion is among those who chose not to vote in the 2016 referendum (albeit slightly muddied by the demographics issue) – W H Y then, have these people now discovered in themselves a change of attitude to voting?Report

FORGET BREXIT.

Forget the last 50 years, imagine they never happened.

Just consider where Britain is today in 2023.

– A nation with a moderately successful economy, although now with limited global influence.

– Very reliant on food imports, immigrant labour and export markets.

– Just 23 miles from the world’s largest and most successful trading bloc, labour pool and single market, offering:

– A market of 420 million people, ready to buy up to 50% of our exports.

– A labour pool of 150 million educated and motivated people at all skill levels.

– Food and goods freely importable and exportable without paperwork or tariffs.

– Even the possibility of free unrestricted travel, jobs and residence in this bloc.

– And potential for the UK to be the ‘gateway to Europe’ for US and Asian companies… (as it used to be)

What would any sensible and rational British politician be calling for?

For the UK to JOIN this amazing union without delay.

We need to get this message across:

Here and now, in 2023, ignoring the past 50 years, and especially the last 5 years, looking only FORWARD, not to be a member of the EU single market and customs union is to ignore reality and act against our own interests. It is simply not rational.

The message could be: Forget the past. The UK, if it has any sense, should JOIN the EU.Report

It’s interesting that the majority of Leave voters think Brexit has failed on almost every measure but for some unknown reason they still support it.

They voted for less immigration, they got more. They voted to benefit the NHS, it’s now in tatters. They voted for economic growth, they got decline. They voted for better wages, they got lower wages. They voted for more international trade, they got less. They voted for more international influence and instead we are an international embarrassment.

We’re left with just one question to ask them – what would failure have looked like?Report

The large UnHerd poll showed that the majority against Brexit is about 2 to 1 – about the same as the 1975 result; rejoining has a smaller lead of over 15% in John Curtice’s poll of polls, presumably because some do not realise that the offer of our old deal is being suggested by a post-Brexit EU law. These poll results have been achieved by the rejoin campaign, even though all the major English parties are campaigning against it. After our right to revoke Article 50 expired (on actually leaving), the EU passed a law, EP 2020/2136 section 30, that approved a 2nd referendum on the final deal, which suggests that failing to approve it in such a referendum cancels and reverses Brexit and gives us our old deal back, with only such changes as may be agreeable or necessary due to passage of time. (Of course the proposition of holding a 2nd referendum on the final Brexit deal does not go against the will of the people as expressed in the 2016 referendum, as the proposition was not defeated because it was never put to a vote.) The EU is unlikely to impose onerous conditions on rejoining, because to do so would be to risk losing the 3rd referendum on the final rejoining terms; obviously it would be hypocritical for the EU not to expect such a referendum. Where is the evidence that the EU is so proud as to want to waste billions to maintain trade friction when trading with Britain?

Ever closer political union is now optional for all members, but alliances (by union or by the usual method of political agreement between states) are urgently required to protect democracy. Such alliances may deter the communists in China from attacking the democrats on Taiwan, in contrast to the encouragement given to Putin to invade Ukraine after a Europe disunited by Brexit was unable to organise the defence of Afghan democracy in the aftermath of the US surrender to the Taliban. We already have this common purpose with our rich former colonies, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US, along with our stalwart ally Poland and our new ally Ukraine. If we join Poland in the EU along with Ukraine, the three of us will form a foundation of an anti-appeasement block that will be strong enough to oppose any pro-appeasement factions in France and Germany; as a result the EU will become part of the global alliance for democracy, which will be strong and rich enough to counter the communists in China.Report

Agreed. Now more than ever, the UK needs to once again become a strong and respected Leader in Europe, not a Leaver.Report

The analysis should be compulsory reading for all MPs, thus allowing them to look at the real world and address said analysis.Report

When I read such articles by John Curtice, I always want to ask this question: “isn’t it extraordinary that there should be such a strong tide of public opinion running against Brexit when neither main party dare speak critically of it, and whilst most daily papers still support Brexit it and avoid any criticism?” Just think what the effect would be a senior Labour or Conservative politician were to speak out about the deleterious impacts of this act of self harm.Report

Why has Brexit become less popular? Because there are literally no upsides only costs. As events have played out, what was promised is simply laid bare as lies. The question is how this will play out. The downside of a plebiscite in a representative democracy is no one political party owns the consequences. There is no magic in any political decision however arrived at – it does not prevent the consequences being visited upon you. So ultimately the public are to blame for this mess. However party politics simply doesn’t work when it comes to telling the public this -.they won’t want to know and there will be a backlash. So we’re stuck with the unreality where we are spiralling downwards due to Brexit, yet politicians talk about “great opportunities” without going to the tedious task of naming, let alone putting a value on them. Brexit broke Britain, economically, culturally and politically. The sooner we are honest with ourselves, the quicker we can fix this. Otherwise it’s years or decades of decline.Report