The conclusion of a new agreement between the UK and the EU on how the movement of goods between Great Britain (outside the single market) and Northern Ireland (inside) has fuelled speculation that it might pave the way for some softening of the UK’s relationship with the EU. Public attitudes towards some of the steps that might be taken in that direction was one of the subjects covered by polling undertaken by Redfield & Wilton Strategies for UK in a Changing Europe last December. Now the latest polling from Redfield & Wilton, released today, examines the subject further.

Three of the questions on which we reported in December, each of them possible ways of softening Brexit, read as follows:

To what extent, if at all, would you support or oppose the UK:

adopting EU laws and regulations on the manufacturing of goods in exchange for the EU not implementing border checks or tariffs on goods produced in the UK?

adopting EU laws and regulations on food and agriculture in exchange for the EU not implementing border checks or tariffs on food products produced in the UK?

allowing EU citizens to freely travel, study, work, and immigrate to the UK in exchange for the EU allowing UK citizens to freely travel, study, work, and immigrate to the EU?

The pattern of responses in December suggested that, while more popular among Remain supporters and those who would like the UK to have a close relationship with the EU, among the public as a whole there was majority support for these propositions. We concluded that there might be more room for softening Brexit than politicians perhaps realised.

But what if we put the contrary to these propositions to voters? For example, do those who support adopting EU rules reject the idea that the UK should have its own rules and regulations that would mean checks on UK goods entering the EU? Or do we discover a degree of inconsistency in the pattern of people’s responses, a pattern that might be thought to raise questions about the firmness of the views that they express?

In their latest poll, Redfield & Wilton also asked the following questions that posited a relatively hard form of Brexit:

To what extent, if at all, would you support or oppose the UK:

having its own laws and regulations on the manufacturing of goods at the cost of the EU implementing border checks or tariffs on goods produced in the UK?

having its own laws and regulations on food and agriculture at the cost of the EU implementing border checks or tariffs on food products produced in the UK?

having a choice as to how many and which EU citizens can travel, study, work, or immigrate to the UK at the cost of the EU having a choice as to how many and which UK citizens can travel, study, work, and immigrate to the EU?

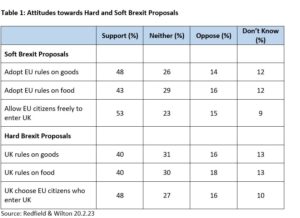

Table 1 shows the pattern of response to all six questions. If respondents had firm views on these issues, we would have anticipated that those who supported the proposals for softening Brexit would have opposed the idea that the UK should set its own rules. However, the level of support for the ‘hard’ Brexit propositions is only a little below that for the ‘soft’ ones, while the level of opposition, at around one in six, is strikingly similar in the two halves of the table.

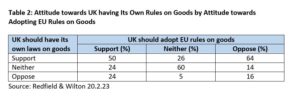

The extent of the inconsistency in the answers given by individual respondents can be seen in Table 2, which shows the level of support for the UK having its own laws and regulations on the manufacture of goods broken down by how people responded to the idea that the UK should adopt EU laws and regulations. While a majority of those who oppose adopting EU rules on goods also say the UK should have its own rules, as many as a half of those who say they support adopting EU rules also state that the UK should have its own rules. Overall, only 45% of respondents gave a substantively consistent response to the two questions.

The picture is much the same in respect of the other two pairs of items in Table 1. Only 50% were substantively consistent in their responses to the propositions on the regulation of food, while just 38% gave consistent answers to the questions on the movement of persons – not least because in both cases a majority of those who supported the soft Brexit proposal also said they backed the equivalent hard Brexit one.

Two possible explanations come to mind. One is a risk to which all surveys are subject – acquiescence bias, that is, a tendency for respondents to agree rather than disagree with any proposition put to them. This can be particularly evident if respondents do not have very firm views on a subject and/or are attempting to complete a survey quickly, not appreciating that the propositions they are answering are worded in opposite directions. The other is that many voters would like the UK to have its own rules and, at the same time, for it to be relatively easy for people and goods to move from the UK to the EU – that is, they are disinclined to embrace the trade-offs that are involved in negotiating a relationship with the EU and their response to poll questions depends on which feature is being emphasised.

One way of trying to avoid these difficulties is to invite respondents to choose between opposing propositions. The latest Redfield & Wilton poll also adopted this approach by asking:

Is it more important for the United Kingdom:

to be able to have its own laws and regulations,

or,

to be able to trade easily with the European Union?

While 39% said it was more important to trade with the EU, slightly more, 47% picked out the UK having its own laws and regulations. As we might anticipate, those who currently support staying out of the EU are heavily inclined (by 72% to 21%) to the view that it is more important for the UK to have its own laws and regulations. However, while those who would vote to re-join the EU are, in contrast, more likely to say that trading easily with the EU is more important, the balance of opinion (56% to 32%) is rather more even – perhaps helping to explain why those who back re-joining are particularly unlikely to give substantively consistent answers to the hard and soft Brexit options in Table 1.

What, though, are the implications for the continuing debate about Britain’s relationship with the EU? First, even after seven years of debate about what Britain’s post-Brexit relationship with the EU should be, many voters appear not to recognise the trade-offs involved. Second, much depends on framing. Those who want a closer relationship need to persuade voters of the value of being able to trade easily with the EU, while those who prefer a harder Brexit need to focus their attention on sovereignty. The outcome of that debate about priorities is far from guaranteed.

This blog is also posted on the UK in a Changing Europe website

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.