In our previous blog on attitudes towards Brexit since the UK left the EU single market, we noted that after oscillating up and down in 2021, the last twelve months witnessed a marked decline in support for being outside the EU. On average, the polls now suggest that 57% would vote to rejoin the EU, while only 43% would support staying out. We also went on to show that much of the decline in the popularity of Brexit is accounted for by a swing away from the idea among those who in 2016 voted to leave the EU.

In this blog we try to account for this swing by examining how Leave voters’ evaluations of Brexit have evolved during the last twelve months or so. We can do so thanks to three extensive pieces of polling that recently repeated questions about the consequences of Brexit that they had previously asked in late 2021 or early 2022.

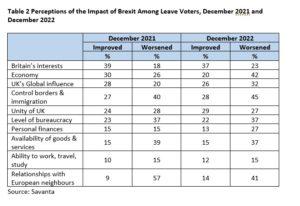

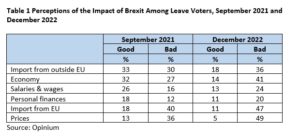

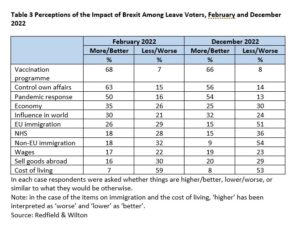

The first of these is polling by Opinium, which at the beginning of December administered questions that the company first asked in September 2021. The second is work undertaken by Savanta, which this December repeated questions that had had been asked a year previously. The third was undertaken by Redfield & Wilton for The UK in a Changing Europe, polling on which we have written previously, and which addressed the issue last February and again in December.

Table 1 summarises the findings obtained by Opinium. They suggest that even in September 2021 relatively few Leave voters thought that Brexit was having a ‘good’ impact on any of the issues covered by the poll; on none of them did more than a third express that view. But in each case the proportion saying ‘good’ is now lower, while those saying ‘bad’ is higher. That suggests that there has been an across-the-board reduction in positive evaluations of Brexit among Leave voters. However, the table also shows that the most marked change of outlook is in respect of the economy. In September 2021, those saying the impact of Brexit has been ‘good’ is down by 18 points, while the proportion saying it has been ‘bad’ is up by 14 points.

In Table 2 we examine the polling undertaken by Savanta at the end of both 2021 and 2022. As in the case of Opinium, the earlier poll did not suggest that there was a widespread feeling among Leave voters that Brexit was making things better – including on the issue of immigration which was not covered by Opinium but which played a prominent role in the 2016 referendum campaign. But in this instance on many items the balance of opinion is little different now from what it was twelve months ago, and indeed in the case of relations with our European neighbours, the proportion who think that things have worsened (41%) is 16 points down on what it was in 2021 (57%).

However, on some items the balance of opinion in Savanta’s polling is more negative now. Moreover, here too, it is on the economy where opinion has changed the most. The proportion of Leave voters who think that Brexit has worsened the economy is up by 16 points (from 26% to 42%), while the proportion who think it has improved the economy is down by ten points (from 30% to 20%). Meanwhile, perceptions of the impact of Britain’s global influence, another subject not covered by Opinium, have also become notably more pessimistic.

However, on some items the balance of opinion in Savanta’s polling is more negative now. Moreover, here too, it is on the economy where opinion has changed the most. The proportion of Leave voters who think that Brexit has worsened the economy is up by 16 points (from 26% to 42%), while the proportion who think it has improved the economy is down by ten points (from 30% to 20%). Meanwhile, perceptions of the impact of Britain’s global influence, another subject not covered by Opinium, have also become notably more pessimistic.

Finally, in Table 3 we show how Leave voters have responded when Redfield & Wilton have asked whether Brexit has made things better or worse than they would have been otherwise. It shows that on two topics that the Opinium and Savanta polls did not cover – the handling of the coronavirus pandemic and the extent to which Brexit helped Britain gain more control over its own affairs – there was a widespread belief early last year that Brexit had resulted in a better outcome than would have happened otherwise. Moreover, in the case of the pandemic at least, including the vaccine rollout, that outlook is still largely undiminished, and it clearly represents one area where the government has enjoyed long-term success in its advocacy of the benefits of Brexit.

Indeed, much like that from Savanta, much of Redfield & Wilton’s polling also suggests that on many items the balance of evaluations has not changed markedly. One instance, however, where that is not the case is in respect of immigration – Redfield & Wilton’s polling shows a substantial increase in the proportion who think that both EU and non-EU immigration is higher now than it would have been if the UK were part of the EU. Otherwise, we should note that here too perceptions of the impact of Brexit on the economy have become more negative, while there has also been some drop in the proportion who believe that Britain has more control over its own affairs.

There is then, one message that emerges with considerable consistency across the three sets of polls. Leave voters have become notably less positive about the impact of Brexit on the economy. Of course, this trend has occurred in tandem with a worsening economic outlook and a decline in economic optimism. It may well be that the responses given by Leave voters about the economic impact of Brexit reflect that wider darkening of the economic outlook (and in their perception of the economic competence of the government that implemented Brexit – see also here) rather than a carefully honed evaluation of the impact of leaving the EU. However, even if this is the case it indicates how difficult it is in current circumstances for Brexiteers to persuade Leave voters, let alone anyone else, that Brexit is proving advantageous economically.

Still, our analysis so far simply suggests that more adverse economic evaluations of the economics of Brexit looks like a possible key explanation of why support for Brexit has fallen among Leave voters. If we are to say more than that we also need to demonstrate that those Leave voters who have a negative perception of the economic consequences of Brexit are less likely than those who do not to say that they would vote to stay out of the EU.

Further analysis that we are able to undertake of Redfield & Wilton’s most recent polling suggests that is the case. As many as 37% of those 2016 Leave voters who think the UK economy is weaker as a result of Brexit now say they would vote to join the EU, compared with only 12% of those who think the economy is at least as strong as it would have been otherwise. More complex statistical analysis suggests that this difference is robust even when we take into account the possible impact of other evaluations on the probability of a Leave voter saying that the UK should stay out of the EU.

But what of the evidence in Redfield & Wilton’s polling that Leave voters have become more likely to feel that immigration has increased as a result of Brexit? Here there is a crucial difference from the economy – the perception that immigration has increased as a result of Brexit is not linked with a change of attitude towards EU membership among Leave voters. For example, while 19% of Leave voters who think that immigration from the EU is higher as a result of Brexit now say that they would vote to stay out of the EU, so also do 19% of those Leave voters who do not think EU immigration has increased. While it may be striking given the role that the issue played in 2016, the apparently widespread perception that immigration has increased since Brexit does not help us understand why support for the idea has fallen.

We are left with two key findings. First, there is consistent evidence in the polls that Leave voters have particularly become more negative in their evaluation of the economic consequences of Brexit over the last twelve months. Second, those who hold that view are less likely to support staying outside the EU than those who do not have such a negative evaluation. In short, it looks as though it is a loss of confidence among Leave voters in the economics of Brexit that, above all, has resulted in some of them rethinking their attitude towards being outside the EU.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

Will you please explain why 63% in Table 3 apparently believe that with Brexit the UK has more control over its own affairs, and yet, when I click on the relevant question on the right-hand side of this page, I am taken to a graph suggesting that no more than 44% have this belief? Even when I eliminate the “Don’t knows” and those responding “about the same” from the calculation, including only those who say “more” and “less control”, I cannot get above 57%. Thank you.Report

The economic effects were always going to be terrible; what I found much more jarring are the cultural, political and social effects. The EU stands for peace, cooperation, friendship, human rights, mutual help … it does not always achieve these entirely, of course, but to leave when things don’t go perfectly like a petulant child clearly was not the way. The UK now has the reputation of a xenophobic, insular, self-obsessed and arrogant country, and that is not going to change in a hurry. Reputations are built in decades, lost in days.Report

Totally agree with Thomas Krebs. It is utterly shaming that this giant con succeeded on the strength of repeated three words phrases like ‘take back control’ and ‘get Brexit done’ .. a jarring reflection on the gullibility of our population, and low standard of education here. Johnson et al have dealt the UK a serious wound. I will never forgive them.Report

You mean England has a reputation for arrogance (always did) and xenophobia.

Brexit was England’s idea, pushed through by English voters, against Scotland’s will, and is fully England’s shame.Report

Totally agree. We might also want to think about the colossal act of self harm done in wales, too – neglected by the government for years, oft-funded by the EU and with generally low rates of immigration but still …Report

It’s really bad for business and 350 million for NHS where is it know.Report