Brexit played a central role in the outcome of the 2019 general election. Those who had voted Leave in 2016 swung strongly towards the Conservatives. In winning an overall majority of 80, the party captured from Labour some Leave-inclined parliamentary constituencies that the Conservatives had not previously won since at least the 1930s. Unsurprisingly, Labour have been keen to reverse these losses by wooing back into its ranks those of its former supporters who voted Conservative to ensure that Brexit was done.

One of the central electoral questions of this parliament is therefore how durable the Brexit divide in the pattern of party support is proving to be. Earlier this year, I argued in a report compiled by The UK in A Changing Europe that the divide was now less sharp than it was in the 2019 election, but was still stronger than it had been in 2015, before the EU referendum was held. In fact, it seemed to be more or less at the level it had reached in 2017.

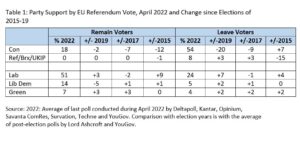

Table 1 suggests that this conclusion continues to hold. Based on an average of the most recent polls prior to the end of last month, it shows that while support for the Conservatives has fallen much more heavily since 2019 among Leave voters than it has among Remain supporters, compared with 2015 the party is still stronger than it was then among Leave voters, while it is weaker among Remain supporters. In contrast, the fall in the party’s support since 2017 is much the same among both groups.

Meanwhile, although the differences are not as strong, since 2019 Labour has advanced more strongly among Leave voters than it has among Remain supporters, while the opposite is the case as compared with 2015. In contrast, the slight fall in the party’s support as compared with 2017 is almost the same in the two groups.

But what pattern might we expect to uncover in the results of the local elections? Most of the seats contested in England were last fought over in 2018, in between the 2017 and 2019 elections. The pattern of seat gains and losses will thus have reflected any changes in the electoral geography of Brexit since then – and not necessarily what has happened since the last general election. However, outside of London, most of the councils that had elections this year also had elections last year – and thus we can analyse these to assess whether the post-2019 decline in the sharpness of the Brexit divide in the polls was also evident in the local election ballot boxes.

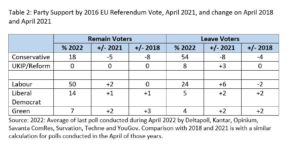

Table 2 indicates what the polls suggest we might find. In contrast to Table 1, this table compares the position now with that shortly before the 2018 and 2021 local elections. It shows that, as compared with last year the Conservatives have lost ground somewhat more heavily among Remain than Leave supporters, while Labour’s advance has been somewhat stronger among Leave voters. However, the comparison with 2018 shows a different picture – the loss of Conservative support since then appears to have been rather greater among Remain voters, while Labour’s position may have been a little weaker then among Leave supporters then than it is now.

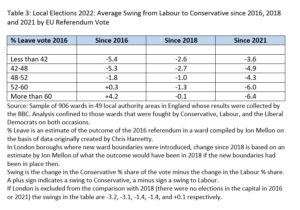

The relative strength of the Conservative and Labour performance in Remain and Leave voting areas in the local elections does indeed differ depending on what is taken as the baseline year. As Table 3 shows, compared with twelve months ago there was on average a bigger swing from Conservative to Labour in wards that voted heavily for Leave than there was in those wards that backed Remain. However, despite Labour’s relative success over the last twelve months in advancing in Leave voting areas, the swing from Conservative to Labour since 2018 was still somewhat lower in Leave voting areas than in Remain inclined locations. Meanwhile, if we compare the outcome in 2022 with what happened six years ago, when the local elections were held shortly before the EU referendum, there was still a marked swing to the Conservatives in Leave voting areas while there was a swing to Labour in more pro-Remain places (albeit the difference was a little less marked than last year).

Not that the picture is exactly the same everywhere. The more marked swing from Conservative to Labour since last year in Leave-inclined wards is less in evidence in the North of England than elsewhere. In wards in the North where Leave were ahead in 2016, the swing from Conservative to Labour averaged -4.5%, whereas in the South (outside London) it was as much as -8.1%. Indeed, whereas for the most part Labour’s performance in 2022 was on a par with (though not better than) four years ago (when Labour recorded its best local election performance under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership) in the North of England the party’s vote was on average three points down on 2018, a decline that was most marked in Leave voting areas. And, of course, it is in the North of England where many of the ‘Red Wall’ Leave-voting constituencies that Labour wishes to reclaim are located.

In the case of the Liberal Democrats, in contrast, the pattern is more straightforward. Irrespective of whether the comparison is made with 2018 or 2021 (or indeed 2016), the two to three-point increase in its support that the party registered on each of those occasions was, in general, much the same in Leave-voting areas as it was in Remain supporting ones – much as would be anticipated given the evidence of Table 2. That suggests the party’s anti-Brexit past had little to do with the increases it secured this time. That said the party’s advance (compared with 2018 and 2021) was closer to five per cent in pro-Remain wards where the Conservatives had previously won at least a third of the vote, indicating that perhaps the party still has the potential to appeal in particular to Conservative supporters who are not especially enamoured of Brexit.

All in all, the local elections appear to confirm the message of the opinion polls that the Brexit divide in the pattern of Conservative and Labour support has narrowed over the last year. The Conservatives’ recent political difficulties have hit them above all among Leave voters and in Leave voting areas – the very core of the party’s electoral success in 2019. However, this has only resulted in a partial reversal of the change in the electoral geography of party support that has occurred since the EU referendum, much of which still seems to be in place. The electoral legacy of Brexit is still very much with us.

Acknowledgement

Much of the analysis reported here was undertaken with the help of Patrick English, Rob Ford, Eilidh Macfarlane, Jon Mellon, and Stephen Fisher. Responsibility for the views expressed lies with the author.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

The original negotiations always ought to have been upon a NO DEAL basis, to which the EU could not have dealt with, given the Russian Coal, OIL and Huge volumes of gas imported to heat also power most of western Europe!!

As it now has to be cut off, with the exception of Germany!!

Ergo Cut Germany out of the European Union cut Germany off from Everything No flights trading by any means, anyone who deals with GErmany cannot deal with either The Americans or the rest of Europe by any means!!

.

Report