The coronavirus pandemic has come to dominate the political agenda. As a result, after three years of rarely being out of the headlines, Brexit is now barely mentioned, even though much remains to be settled so far as the UK’s future relationship with the EU is concerned. Meanwhile, far from being an issue on which voters are divided, there is agreement across the political spectrum that some way needs to be found to manage and perhaps eventually ‘defeat’ the virus – the only point of dispute is how this might best be achieved. This unity of purpose has helped engender a ‘rally to the flag’ effect that has served to boost the personal popularity of the Prime Minister and underpinned relatively high levels of satisfaction with how the government has been handling the crisis.

Given this backdrop, one can understand why it might be thought that the divisions of the Brexit debate have been left behind and that the country’s electoral landscape has been fundamentally redrawn. However, a look at recent polling suggests this is far from being the case.

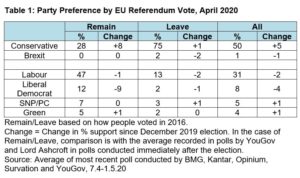

In the table below we show separately for those who voted Remain in 2016 and those who backed Leave the average level of support for the parties as recorded by polls conducted in April. It also compares the current position with how people voted in last year’s general election, as measured by polls conducted by Lord Ashcroft and YouGov.

As was the case in the general election, the Conservatives dominate the political preferences of Leave voters, three quarters of whom currently say they would vote for the party. In contrast, Labour is still by far the most popular party among Remain supporters, nearly half of whom say they would vote for the party – again, little different from what happened last December. The Brexit divide is still very clearly in evidence so far as the pattern of party support is concerned.

True, what is noticeable is that support for the Conservatives has advanced somewhat among Remain voters, while staying relatively static among Leave supporters. At 28% the average level of support for the party is eight points up on the figure recorded at the election. To that extent at least, there is some evidence that the reaction to the coronavirus pandemic has served to reduce the width of the Brexit divide, and that the Conservatives’ fortunes have been restored somewhat among a group where they declined markedly between 2015 and 2019. From the table, it looks as though much of this progress by the Conservatives among Remain supporters has come at the expense of the Liberal Democrats, who were the most popular choice in December for those Remain voters who defected from the Conservatives between 2017 and 2019 and who perhaps have now returned to the fold. However, an examination of the detailed poll figures on how voters have switched since December suggests that is only part of the story. In practice, Liberal Democrat voters appear to have switched to the Conservatives and Labour in roughly equal numbers, but the Conservatives have been the net beneficiary of switches between themselves and Labour.

This picture of a continuing and only slightly narrowed Brexit divide is also in evidence if we look at voters’ evaluations of the Prime Minister as measured by Opinium. As we might anticipate, during the election Mr Johnson was much more popular among those who voted Leave than he was among those who supported Remain. On average during the campaign, as many as 64% of Leave voters told Opinium that they were satisfied with the way that Mr Johnson was handling his job as Prime Minister, while just 20% were dissatisfied. In contrast, the position among Remain voters was almost the exact opposite, with 20% expressing satisfaction and 66% dissatisfaction.

The Prime Minister is now more popular than he was during the election among both groups – just as we would anticipate from a ‘rally to the flag’ effect that cuts across existing political divides. However, Mr Johnson is still much more popular among Leave voters than he is among their Remain counterparts. On average in the last month’s Opinium polls, no less than 77% of Leave voters have said that they are satisfied with how Mr Johnson is handling his job, while just 12% are dissatisfied. In contrast, Remain supporters are more likely to be dissatisfied with the Prime Minister (47%) than satisfied (37%).

What is true is that the gap between the two groups has narrowed a little – the proportion of Remain voters who are satisfied with the way Mr Johnson is handling his job has increased by 17 points, while among Leave voters the increase has been a more modest 13 points. But even though voters may have rallied to the flag during the pandemic, that does not mean that the political divide created by Brexit has disappeared – and on current form it is still likely to be with us when the immediate public health crisis is over.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

I think that those who call for an “extension” to the Brexit FTA talks should at least tell us what an extension is supposed to achieve, and what problem, exactly, they think they are addressing.

The UK presented the EU with a draft FTA as long ago as February, and has also published a list of tariff levels that it would use in the case of a WTO Brexit. But in response, the EU has insisted in discussing jurisdictional issues – EU jurisdiction over UK fishing areas, EU oversight of UK competitiveness, EJC jurisdiction over trade negotiations, and so on.

It’s pretty clear that neither time nor network communication has been the limiting factor, since the EU has been routinely conducting its daily business by network meetings, and also since the EU has apparently had ample time to set up entire new internal fiscal and economic stimulation mechanisms around Covid.

When the real reason for slow progress has been the EU’s insistence on pursuing legal mechanisms to subordinate the UK to the EU and its Courts, an extension will simply give the EU more time and space to continue to try to change the nature of Brexit; trying to make the UK a non-member, but also non-sovereign extension of the EU.

The EU knows that as long as “FTA” talks are allowed to continue it can warp them into talks about EU control of UK trade, and the way the Treaties are written, the only way the UK can bring these talks to a conclusion and re-establish its sovereignty as a fact is not to ask for an extension, and not to agree to one if the EU asks for it.Report

Support for extending the transition period past the end of 2020 is only 43% compared to 37% against, according to Yougov’s polling. A 6% lead, whilst greater than the 4% lead for leave in the Referendum, isn’t convincing evidence that the country supports a particular policy.

https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/survey-results/daily/2020/05/15/573f2/1

Report

As usual the Prof does not even bother to mention the most recent poll (currently featured on this website); showing a big big majority for delaying negotiations on the EU settlement. It is quite a remarkable poll for the hard Brexit “getting it done’ stance, which is very much the government”s position, is trounced, which must mean a backing from many Leavers as well as Remainers .

But then Curtice rarely reports or comments on any polls favouring the Remain position.Report

I wish the Media would join in the ” Rally round the flag ” instead of relentlessly digging for any bad news to hit the government with.

One BBC presenter finished an interview with a bereaved relative with the question, ” Who no you blame? ” What a question!!!Report

Philip, has it occurred to you that the media may be better serving the interests of the UK by actually subjecting the government to the scrutiny which seems sadly absent at the moment in parliament? This is not North Korea or China or even Russia, and it’s not the job of the media to be cheerleaders for ministers. Some of us think the Johnson government’s record has been shocking. The same type of ‘don’t rock the vote’ sentiment may well have been voiced in May 1940 when the Chamberlain government was struggling badly at the start of WWII. Had it prevailed, Churchill might well have not become prime minister and we might have lost the war. Report

Don’t rock the boat, of course. Freudian perhaps. Report