Have our attitudes towards remaining in or leaving the EU changed at all? In publishing today a ‘EURef2 Poll of Polls’ and backdating it to the beginning of this year, we are now able to provide a simple summary of the evidence that the polls are providing on this question.

The first thing to note is just how extraordinarily stable the picture has been during the last nine months. We started the year with Remain on 52% and Leave on 48% – and our latest poll of polls also shows Remain on 52% and Leave on 48%.

Moreover, the picture has barely changed at all during the intervening months. Support for Remain did fall slightly in March when a couple of polls put Leave ahead. Momentarily the two sides were neck and neck in the poll of polls. However, by the end of April the figures had returned to where they had been at the beginning of the year. More recently, it appeared as though there might have been a bit of a swing in the opposite direction, with Remain edging up to 53% and Leave down to 47% in the wake of the publication of the Chequers Agreement. But that movement too has subsequently looked to be short-lived.

In short, neither side in the Brexit debate has secured any ‘momentum’ so far as the balance of public opinion is concerned – and any claims to the contrary made by protagonists on either side of the debate should be regarded with considerable scepticism. But, of course, what our ‘poll of polls’ does show is that the balance of opinion is now tilted slightly in the opposite direction from that which emerged from the ballot boxes in June 2016. Indeed, this has not only been the position throughout last year, but also in most polls ever since last year’s general election.

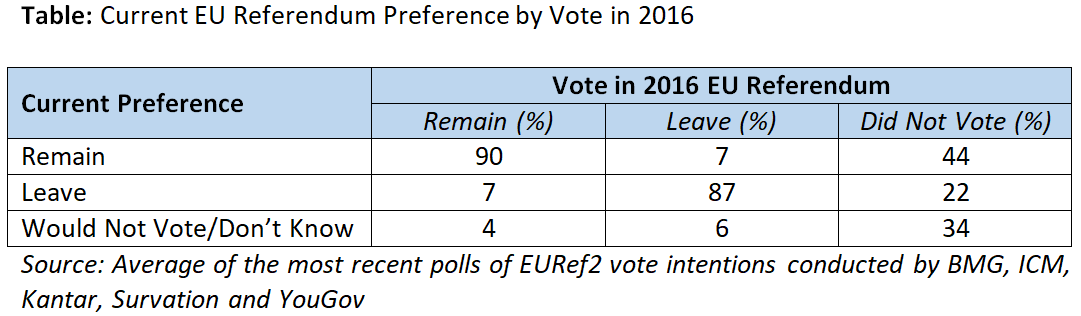

However, this does not necessarily mean that many a Leave voter has changed their mind. This becomes clear if we look underneath the bonnet of the headline figures and examine separately how those who voted Remain, those who backed Leave, and those who did not vote at all, now say they would vote in another referendum. This information is shown in the table below, which is based on the average of the most recent poll conducted by each of the five companies that have polled within the last month or so.

There is some evidence that those who voted Leave are a little less likely than those who voted Remain to say that they would vote the same way again. Such a pattern is found in some though not all polls – and indeed was also found in the most recent wave of NatCen’s panel survey. Thus, when we average the figures out across a number of polls, we find that 87% of Leave voters say that they would vote the same way again, a little below the 90% of Remain voters who say that they would do so.

What, however, is to be seen in every poll is a marked tendency for those who did not vote in 2016 to be more likely to say that they would vote Remain rather than Leave – though note that many do not indicate a preference at all. Some of these will be voters who were too young to vote two years ago, while others will be those who for whatever reason chose not to do so.

This suggests that in practice the outcome of any second referendum might well depend on the extent to which those who did not or could not vote first time around actually make it to the polls. Disproportionately younger voters as they are, past experience suggests that there is certainly no guarantee that they will do so in large numbers. Equally, identifying who will and (especially) who will not vote is one of the more challenging tasks that faces pollsters. At this juncture at least, and bearing in mind too that polls are not always perfect, the only safe conclusion that can probably be drawn is that that the outcome of any second ballot would most likely be close – just, of course, as the first one was.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

There is one question that no-one seems to be asking. Suppose that there is a No-deal Brexit. What would happen on the Northern Irish border on the 1st of November? Presumably, you could not leave things as they are – and so there would have to be border checks. In other words, No-deal Brexit is a very long way from being a “solution”.

And if that were to happen, and the people of Northern Ireland were asked what they would like to do, what would they vote? Given that they already voted 55.8% in favour of remain in 2015, and a mess at the Irish border would be very problematic, could it be that they might actually prefer to join the Irish Republic?

In a sense, that would a real “solution” to the whole Brexit problem. Northern Ireland joins the Irish Republic, and the rest of the UK leaves the EU. Report

I would be interested to see the “Did Not Vote” category broken down to distinguish between the views of those who were eligible to vote but did not do so, for whatever reason, and those who – like myself, an EU citizen living in the UK (for 32 years) – were not eligible to vote (accepting that this group itself would have been split into “would have voted” and “would not have voted”). In that “not eligible to vote” category the poll should include the views of UK citizens living in the EU and of EU citizens living in the UK, and include young people (16-17 year olds). I feel there’s a big difference between “could vote but didn’t” and “could not vote”, and within the latter category I suspect there’s a significant proportion who would have been very keen to have their say. If the franchise had been wider in the EU Referendum I am confident that the result would have been to Remain.Report

Very interesting analysis. Would be interested to see a similar analysis a year later.Report

Isn’t the critical factor the willingness to vote in a future referendum? Had the younger voters who didn’t vote in the referendum actually turned up, the result would have swung to the ‘remain’ side. It’s nearly always the same story: there is a gradation of voting by age: the younger the vote, the greater their likelihood of not voting. The issue for all campaigners is to target their ‘base’ of potential voters and stir them to vote. Right now, it’s the older voters – especially the OAPs who have no job to lose – who are the most likely to vote. And the younger voters – especially the u25s – whose prospects are most at risk who’re most likely to forget to vote. Report

The most telling thing for me is the language being used by all news organisations ,all pro remain MP’s and businesses and by many many speakers on news programs and reports over the past few months .Precipice, catastrophe , cliff edge , Crashing out, the rhetoric and language used by news organisations has been diabolically in favour of the remain camp .Every time I have watched or listened to the news I keep being told that leaving the EU under any terms other than remaining in the EU will be catastrophic for the UK .Considering project fear has been ramped up to epidemic proportions its not surprising that polls indicate this swing back to the remain result .No doubt the current push for a second referendum has been buoyed by these results . The only issue they have is phrasing the question in the correct way to guarantee the result they want .One of those is to ensure that no deal IE trading on WTO rules is not an option . Report

Brexiteers have a romantic yearning for the days when they spent most of their time at the roadside waiting for the AA to repair their Austin Brexit car, which had struggled to roll off the production line at the strike-hit British-manged British Leyland car company, before returning home to face an evening of darkness as the electricity supplies were cut off due to the coal miners holding the government to ransom. It is an anathema for a Bexiteer to accept that joining the EU ushered in several decades of strong economic growth and stability, delivered almost entirely by a highly educated, hard-working European workforce, which poured all of its energy into the economy, providing jobs for the UK population through successful foreign-owned companies (BMW, which assembles the German-built Mini and the Bentley, JLR, which assembles the Indian-owned Jaguars and Land Rovers, the German company Deutsche Bahn, which owns most of the British train-operating companies, the German-owned Aldi and Lidl supermarkets and the French, German and Spanish-owned energy suppliers EON, EDF and Scottish Power, to name just a few). Report

The 38% of the electorate who voted Leave (17M out of 45M eligible to vote) are either too rich to notice the imminent economic collapse, too poor to feel any worse off, or too old to care. They believe that Britain is still a great colonial power, which deserves privileged treatment, something that the EU and its citizens don’t provide. They are happy to sever all ties with the EU, bringing about the destruction of a diverse, successful and flourishing economy, as they imagine that this will lead to a return of the colonial glory days of the past. Brexiteers truly believe that once they have flicked the switch they will enter paradise. They are happy to destroy the lives of so many innocent young people who despair at the thought of living the rest of their lives economically isolated from the world. This collective narcissism is based on a sense of inferiority and jealousy and is a stark illustration of a deep neurosis which has taken root amongst a significant proportion of the English population. The Government needs to be tough not only on Brexit but also on the causes of Brexit. Furthermore it must acknowledge that two thirds of the British electorate didn’t vote for Brexit.Report

I have found this analysis very interesting.

I have just been reading Dominic Cummings article on his Brexit Campaign:

https://blogs.spectator.co.uk/2017/01/dominic-cummings-brexit-referendum-won/

He agrees that many people voted without in depth research into the EU or the claims of either side.

He also points to the fact that it was a very close run thing which turned on a number of points colliding at the same time. So a strong element of random event that could not be predicted and might not be repeated.

He said they had a three pronged attack of Turkey/NHS/£350 mill. He also said that even with in the campaign team they had not all appreciated the importance of the NHS Funding Argument and names the NHS £350 mill per week as critical.

The question that this data raises, armed with what is know now, many people who voted would do so the same way again.

It does rather beg the question of how many people still believe the £350 mill figure despite (as Dominic admits himself) that there was only ever half that NET to spend on anything and this has been widely publicised?

In addition, the Expectations of what people were expecting from Brexit was assessed in July 2016 and are clearly at odd with what is being proposed. Interesting, Dominic said that they did not cover the Single Market much and yet the majority of Leave Voters indicated that they expected to stay in the Single Market, the ‘Cake & Eat It’ Promise perhaps but that was Boris’s message rather than a General part of the 3 pronged attack described by Dominic.

The other point is that those who did not vote seem more like to vote Remain, but does that mean that they would go out an vote, as opposed to a view that they now support but do not act upon?

I always wondered if the Polling used then was misleading because if the methodology requires telephones how do you reach all those people with Mobiles, even ‘Pay as you go’ ones? My hunch is that their views might be different form those who had access to a landline.

Finally, much is mentioned in the following notes about Young and Old people. Now I may be wrong but it is my understanding that in the 1970s young people would vote and it has only been in the last 20 years that young people have become less inclined to do so. People of my parents era (both now gone) felt that Democracy had been hard won in the Second World War and always voted. I agree that young people have much to win or lose in the next 10 years, but does that mean that they would vote in higher numbers or does that current apathy still linger?

I shall look forward to your thoughts.

Report

I am a former Canadian soldier posted to Germany during the Cold War. The entire concept of the EU was to bring together similar thinking people that were constantly at war with each other. The idea is to reduce wars and open trade, borders, and movement of people between members.

Certainly there “feels” like a downside to this if you don’t like new ideas, people with accents, and truly are nationalistic. But the upside is this: You ARE all Europeans. How many times will you repeat the same mistakes? In the last 30 years or so you have banded together, opened your borders, and adopted (in general) a common currency. Yes it creates new problems, but are they problems? Seems obvious to me that these problems perceived are MUCH less dangerous that being at war as usual.Report

In all the debate, no one is discussing the possibility of families being split up if EU immigrants may be forced to leave even if they own homes and/or are married and have children here.Report

The major factor that most have ignored is the financial effect, which was glossed oiver in the Referendum, due to the claim that we would get loads of money back from the EU when we left. That has been shown to be Project Fantasy, and now all the economic analyses are showing that it will cost the country to be out of the EU. The hit in the average pocket may have an effect on how voters choose. Many voters are already unhappy with their finances; this may tip the balance.Report

It is interesting how completely people fail to understand simple facts about polling. Take a group of people and ask them how they will vote. That gives you a margin of error. Now after the 1st vote ask people what they voted before and how they will vote now. The margin of error now is a lot lower.

The data shows a clear shift for remain fueled by those who didn’t vote in the first round. That is the data. There is also the zombie myth that people become more likely to vote tory when they get older. That is utter nonsense. People become more likely to vote tory when their income becomes higher, but that is not the tories who voted leave. Those are the tribal voters.

It is quite clear that the electorate is losing its nerve with brexit and when brexit does go wrong, the shift will be rapid and dramatic. Report

Your own poll stats on ‘In hindsight, do you think Britain was right or wrong to vote to leave the EU?’ shows a completely different picture. It was the default poll on your homepage up to a few weeks ago. We’ve been building to a 7% lead for Remain since July last year.

I understand that these are different questions, but I really don’t believe that this country is full of people who think Brexit is a mistake but don’t want to change it. John Curtis seems like a thinly disguised Brexiter to me, not that it matters much, but it’s quite clear that the mood is changing in the UK.

Report

The last poll before the vote in June 2016 also showed 52-48 to REMAIN did it not?

Surely, all this poll suggests is that nothing whatsoever has changed.

John, you are well aware of the concept of “shy Tories”. Given all the vitriol emanating from REMAIN voters is it possible that “shy Leavers” also exist?Report

An interesting analysis, but I get the impression that Steve is a strong Brexiteer. While I have never believed in the European vision – I voted against all those years ago – what I am seeking is an analysis that puts both sides of the argument for pro Chequers and anti Chequers so that there can be a better understanding of why both sides feel so strongly.Report

Mike I voted to remain and would do again not out of political inclination or tribal loyalty but because I think the national interest would be better served by Britain remaining in the EU. However, that is not an option at the moment so we have now reached a point where we have to weigh a national crisis against a global one. If the EU allowed Chequers to pass then there would be no reason why some other member states would not want that arrangement i.e. access to the single market without all the associated liabilities and responsibilities. At that point the EU and the euro starts to unravel, an event that would deal such a massive blow to the world economy that it would be in nobody’s interest.

The pro-Chequers argument, such as it is, is that it would sort of meet the promises made in the referendum – control of immigration (subject to the mobility terms of a trade deal), repatriation of sovereignty (except where it has to be pooled under a trade deal), no on-going payments to the EU (except for those made for access to those agencies the UK wants to be a part of and those already committed to up to the end of the transition period), the ability to strike trade deals with other nations (according to the EU rulebook on goods, but not services, and therefore subject to Brussels and the ECJ), withdrawal from the customs union (but an untried technical fix for Ireland).

There are two obvious problems for the EU:

1. opting out of a common rule book for services (80% of the UK economy) threatens unfair competition for those EU businesses that have to comply with EU regulations in that sector

2. withdrawal from the customs union without a credible technical fix means a hard border in Ireland – something that both the British government and the EU have said is unacceptable because it threatens the Good Friday Agreement, which ended the civil war in Northern Ireland.

Unless these can be resolved there will be no deal. The likely fix is that the UK extends the rulebook to services and Northern Ireland remains in the customs union until a credible alternative can be found. However, the chances of the British Parliament passing that are slim, hence the likelihood of no deal, which given the alternative – that is to say the undermining of the single market and the consequent global catastrophe – is the least bad outcome, albeit a disastrous one for Britain.

It saddens and worries me that we have reached this position, as it must most people regardless of how they voted.Report

Steve – that is a thoughtful analysis, and I am sorry to have mis-read you! I see your logic. The only point I would make is ‘disastrous for Britain’ needs to be counterbalanced by ‘disastrous for France’ and others as well. Much of the wine production from the mid-French valleys/South West France are exported to the UK, but UK importers will be able to source the major selling Sauvignon Blanc at a much cheaper price from NZ, Chile, and Australia. China has offered an astonishing deal using the indigenous grape giving quality wine, which would mean that retailers here would treble their margins, and consumers would see price drops of at least 25%. Our importers are desperately hoping for a no deal Brexit, but dare not say it out loud as it would destroy the French growers in the Loire and Garonne valleys, which would almost certainly cause the end of Macron. Tractors on the Champs-Elysees! There are many other European examples.Report

Yes, no deal will be bad for the winemakers and car manufacturers of the EU, but not nearly as bad as the demise of the single market would be for them, or indeed us. It seems to me that there are no happy endings on offer, just a choice between bad and catastrophic. For the good of the world economy, the only responsible thing is for the damage of Brexit to be confined to the EU, which at the moment can only be achieved by a no deal. That will hit Britain hardest of all and deliver a painful dead-leg to the rest of the EU, but the EU is a far larger economy than ours and will be able to mitigate the effects more easily.

Welcome though a drop in the cost of a bottle of wine would be, I’m afraid it won’t blunt the severe damage to the British economy. Yet, with the options before us as they are, that is to say a British government seemingly unable to pass a compromise through Parliament, we must hope for a no deal because the alternative of the break up of the EU would have truly appalling consequences throughout the world.Report

Steve – I watched the European Commission proceedings yesterday on live tv. The difference between last year and this was striking. Last year proposals were agreed to agree further quotas with Turkey, set up enclaves in North Africa, re-distribute member quotas, and so on. This year country after country rounded on Juncker and co. for their complete paralysis. Zero delivered.They looked like men who will not be there after the elections early next year. In the face of rising domestic unrest countries are taking the law into their own hands. North African immigration is starting to ramp up, so things are getting a whole lot worse.

The EU is now in deep trouble, there for all to see. You are of course right in saying that it has the stronger economy, but whereas a no deal will be painful for the UK, undermining core industries within EU members such as agriculture in France and car manufacturing in Germany at this time may have dis-proportionate political consequence. Small wonder that the last thing Barnier and co. can afford to do is to show weakness on UK leaving.Report

I completely agree that the EU faces a severe problem with illegal immigration, and that it has been slow to find an effective strategy. The current policy, which appears to be to contain the immigrants in the regions from which they come, has had some success in terms of a fall in arrivals this year, but as with so many solutions it is hardly an enticing one. Yet the alternative of allowing everyone in is worse for the stability of Europe, so what else can we do.?

The single market is a different matter. None of the EU 27 is seeking to break it up and there is agreement among them over the terms of Brexit. As far as the EU 27’s ability to protect its manufacturing from a no deal Brexit, the percentages demonstrate why they will be able to do it. While Britain does buy a lot of cars and agricultural produce from the EU, the British market is not so significant for them as the EU’s market is for us. GDP of the EU is about $19 trillion, GDP of the UK is about $2.5 trillion. The EU 27 exports about 12% of its entire car production to the UK, the UK exports about 45% of its entire car production to the EU 27. The EU 27 made 19.5 million vehicles last year and sold about 2.3 million of them to the UK; the UK made 1.7 million vehicles and sold about 800,000 to the EU 27. Consequently, while no deal will damage the EU car manufacturers, the EU will be able to mitigate a reduction in the size of the UK market more easily than we will a reduction in the EU market. We see similar figures across most sectors, hence my view that no deal will be bad but manageable for the EU and catastrophic for the UK.

There will be a change in EU personnel next year. Tusk and Juncker are due to retire in 2019 and Barnier has already said he will move once Brexit is agreed. However, this is not about personalities in Brussels or in the presidential palaces of the member states, or indeed Downing Street; it is about protecting the single market. Whichever way we voted in the referendum none of us should hope for its demise because the global economic consequences will be as bad as the 2008 financial crisis and probably worse because the world economy would have received two massive blows in such short succession. And that would be even worse for Britain than a no deal because our only chance of surviving a no deal is a thriving global economy. If that went into deep recession, as it would do if the EU collapsed, then we and the rest of the world enter extremely dangerous territory.

The only way I can see of averting the local catastrophe of no deal t is for the UK government to compromise on the customs union and to extend the common rulebook to services. However, it seems unlikely that the government could get it through Parliament, so that leads to the scenario I outlined at the start of this thread (which, by the way, I’ve enjoyed writing and thank you for starting!)Report

What is missing from the whole debate is a rational summary of the essential differences between Chequers and a No-Deal that can be debated, rather than the increasingly hysterical assertions being made by both sides. Perhaps John could provide one.Report

Chequers would undermine the single market, which would lead to the unravelling of the EU, and that would have catastrophic consequences in the world economy. No deal would severely damage the UK economy and would have bad but manageable consequences for the EU but would not threaten the destruction of the single market. On balance, nobody should wish for Chequers because it is unlikely the world could peacefully withstand another major economic shock so soon after the 2008 crisis. So if the only alternative is no deal, then no deal it will be and all that flows from it.

At that point the government offers a general election or we enter a constitutional crisis in which the Supreme Court has to interpret the law and direct Parliament as to what it must do. In the second scenario, the Queen then intervenes and asks Parliament if it can form a government of national emergency. If it cannot, then it must vote for a general election. Meanwhile, partly in anticipation of a Corbyn government, there is a run on sterling of between 15-20% and the Bank of England puts up interest rates and the government slashes taxes with drastic consequences for public services. And that is the best we can hope for unless our MPs work in the national interest and allow the government to accept the Norway option.

The worrying aspect is that nobody in our government can see that Chequers would have even worse consequences because it would deliver a massive blow to the world economy just as it is staggering to its feet after the last one.Report

No government would put an option called No Deal to the electorate, rather they would spell out the mechanisms available to countries who are not EU members for trade with the EU . This would be a lot more specific and detailed than the Leave that people voted for in 2016. The bills to repatriate powers to the UK parliament have largely been drafted, so we know much more about how we would run our domestic affairs outside the EU; agriculture, fishery, immigration, environmental regulation etc etc.Report

Do you think there’s a “shy leaver” effect as may also have been seen in the original referendum? The media constantly promotes a remain narrative while remainers still infer if you want to leave you’re a stupid racist bigot. It’s surely likely that many leavers won’t admit their intentions in public, but a very powerful thing to be able to go into the polling booth, know that’s not the case and actually be able to express yourself.Report

Remain has relied heavily since 2016 on fear of ‘a leap in the dark’, and the claim that ‘people didn’t understand what they were voting for’, but a second referendum would presumably be on a withdrawal agreement which had been reached between the EU and UK negotiators as a mutually acceptable and workable future arrangement . Probably that had gone through Parliament. Nothing like that was on the table in 2016. A game changer, one would think.Report

If it had gone through Parliament, it is less likely that it would put to a referendum at all. Whether it had or not, the game changer couild work in either direction, but in theory in favour of Remain – given that no kind of deal is as good as full EU membership, and that no-deal would be greatly worse than either.Report

For all their protestations about Project Fear, there is one fearful fact that leavers cannot ignore, namely death. Given that the older generation largely voted leave and the vast majority of deaths occur in that group, and given that the younger generation overwhelmingly voted remain, the scales tip fractionally and irreversibly towards the latter every day. Report

Not necessarily, Steve. While you are correct that old people, who are disproportionately leave-voting, die at a faster rate than young people, and are ‘replaced’ in the electorate by disproportionately remain-voting young people, the cohort who would be voting on this question for a second time will be slightly older and thus slightly more leave-inclined, in the same way that young people are disproportionately left-wing, but tend to become increasingly conservative as they age. Indeed, with UK life expectancy increasing by 1-2 years per decade, and the median age currently increasing by a month every year, you may see the opposite effect that you hope for, that is, a population which is increasingly dominated by leave-voting oldsters.Report

The people who are moving into the older age bracket are likely to have a larger proportion who attained qualifications, went on to tertiary education and mixed with EU colleagues. Breakdown by education level shows an overwhelming bias towards Remain among this cohort.

|There is no guarantee that these people would tip into voting Leave, based on their own ageing. Their tendency to conservatism might take the form of wanting to conserve those EU benefits that they’ve come to enjoy.Report

That correlation is also skewed by the fact that so many younger people attended university compared to previous generations. It is not necessarily true that going to university makes them more pro EU in the long term.

As for mixing with foreigners, plenty of older people mixed with fellow Europeans in the war (I’m not being facetious) and didn’t come away in favour of political union.

As the memory of the horrors, and the cooperation of European war fade I would expect the case for European union to make even less sense to future generations. Report

The major difference isn’t so much among those leaving the voting population as those entering it. Elderly voters are only 60:40 pro-leave, but 18 year olds are 80:20 pro-remain. Report

The trouble with this argument is that it has been around since at least 1975, and has in fact got more wrong.

Most of those old people who were anti EEC in 1975 are now dead and most of those young people who voted to stay in in 75 are now old and voted Leave.

In other words it is not a shift between people born on or after a certain date so much as a fact of people being a certain age at the time of the vote.

As the average age of our society is getting older and people are living longer it is likely that more young people will become old than old people will die, thus any future referendum could show an even stronger Leave vote.

I haven’t seen any analysis but my hunch is that this voting pattern reflects mostly that retired people with pensions and houses owned outright are less concerned about economic disruption than younger people with mortgages dependent on income from employment. I would be interested to see how the 2 referendum results correlate with the demographic changes over this time. Report

Like you I think a 2nd referendum may well confirm the original vote to leave. However, I think that would be a result of the emotive power of a ‘Surrender’ narrative more than an aged-based drift towards the Conservative Party.

While it is often said that the older people get the more likely they are to vote Conservative, I wonder if that is demonstrated by the voting demographic over the last 70 years. Do you know of any good quality research on that subject? I’d like to read some if it exists.Report

I agree that a surrender aversion may be a factor and that would quite possibly strengthen the Leave vote, perhaps even giving a more decisive Leave result than 2016. Purely anecdotal and very small numbers but I have met more people who voted Remain and who now say they would vote Leave than vice versa.

I think the age link is usually more to do with small c conservative policies than the actual Conservative party, and Brexit epitomises this. You only need look at the huge swathes of northern England which are reliably red on election night yet were solidly Leave in 2016.

Report

I think these Polls are interesting but I wonder how helpful they really are.

Any further referendum will not be a re-run of the first in the sense that there will be much greater precision about the alternatives. The choice will not be between Remain or (simplistically) Cake which allows voters to cast their vote for whatever flavor of leave they like.

Instead the choice is likely to be between Remain and something relatively specific with rather clearer advantages and disadvantages. Next time (if there is one) voters may thus cast their votes our of emotion or be more influenced by reason and experience. I suggest that it is too early to tell.Report

What might the impact be of those younger people who will find themselves able to vote now as they’ve

‘come of age’ ?Report

That’s the big question, I reckon. After all, the people it will most affect will be those still needing to work for a few years after 2020 (as retirees have got pensions together already, and their sufficiency is unlikely to be heavily affected by Brexit, unless they live abroad). Given that you can now retire at 55, that means anyone under the age of 48 today will still have 5 years in work minimum in 2020. But in reality it’s those with longer working lives to come that would be most at risk of any negatives for the world of work. So I reckon the under-40s are the most affected. The evidence I’ve seen suggested they voted Remain.Report

Thank you for the calm, evidence backed analysis. So refreshing to find one.

I believe the polls before the referendum showed a similar margin for remain, yet the vote was to leave.

Relevant data here: https://www.whatukthinks.org/eu/opinion-polls/euref2-poll-of-polls/

This seems significant to me, would you agree?Report

Possibly, but also note that if you go back further ( https://www.whatukthinks.org/eu/questions/should-the-united-kingdom-remain-a-member-of-the-european-union-or-leave-the-european-union-asked-after-the-referendum/ ), there was a shift in opinion over that period that started from the ‘correct’ result.

This is also reflected in related trackers such as yougov’s right/wrong question that started in early autumn 2016 showing agreement with the june referendum – ~48 wrong, 52 right, and is currently averaging something like 53 wrong, 47 right.Report

There were also a lot more people saying “Don’t know” before the referendum, making it much harder to gauge people’s intent as they themselves reportedly didn’t know.Report

Not so surprising I think. Psychologists, I believe, suggest that it is hard to change people’s feelings through rational argument. The referendum was fought on emotion, not facts.

The country offers no consensus on the EU. We don’t know, on the whole, whether to leave or not.

We didn’t in 2016 and we don’t in 2018.Report

What is surprising is that despite the incessant anti-Brexit publicity of the news and media over the last two years and the absence of anybody to put the arguements for leaving the EU (Vote Leave existing for the purpose of the Ref campaign only and the Government not really believing the case). the Leave vote has held up so well.

Of course the outcome of any future vote on the EU will be partly determined by whether the Ref’s non voters turn out but also whether the 3 milllion or so voters who do not normally turn out at General Elections and who, one suspects, were Leave voters in the majority, can be mobilised again. One of Vote Leave’s biggest successes and one of the most pleasing aspects of the Ref as a whole was the turnout. Report