Ever since the 2016 referendum, it has been commonplace for polls of vote intention to report separately the figures for those who voted Remain and those who backed Leave. And as we have previously shown, these analyses suggest that since 2019 there has been a narrowing of the difference between 2016 Remain and Leave voters in their party preferences. Nevertheless, the two groups of voters are still as far apart as they were at the 2017 election.

However, these breakdowns rather ignore the fact that, as we illustrated yesterday, some people now express a different view about whether the UK should be in or out of the EU than the one they backed six years ago. At the same time, anyone younger than 24 will not have been able to vote in the referendum. As a result, only looking at how people voted in 2016 is perhaps at risk of failing to provide an accurate portrayal of the current difference between the party preferences of supporters of EU membership and those of their opponents.

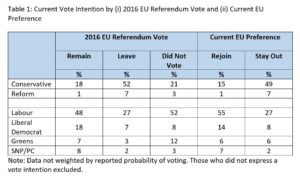

To assess whether that is the case, Table 1 analyses people’s current vote intentions in the latest Redfield & Wilton Strategies poll for UK in a Changing Europe both by how they voted in 2016 and by their current preference for joining or staying out of the EU. The two parties that backed Brexit in 2019 are grouped together as are all those who in 2019 were willing to contemplate holding a second EU referendum.

The first striking point to emerge is that those who did not vote in 2016 are much closer in their current party preference to 2016 Remain voters than they are to those who backed Leave. Just 24% support one of the pro-Brexit parties, while 75% back one of the parties that were once supportive of a second referendum. These figures are only marginally different from the equivalent figures of 19% and 81% among those who voted Remain. This, perhaps, is not entirely surprising given that those who did not vote in 2016 prefer rejoining over staying out by 39% to 29%.

Meanwhile, if Brexit is still one of the considerations that affects people’s party preference, we might anticipate that the link between people’s current attitude towards EU membership and their party preference is stronger than that between their 2016 vote and their current preference. Yet this proves not to be the case. True, Labour performs rather more strongly among those who at present are in favour of rejoining the EU (55%) than it does among those who backed Remain in 2016 (48%). However, at 82%, the proportion of rejoiners who are currently backing one of the parties that supported a second referendum is little different from the 81% of Remain voters that do so. Meanwhile, support for the Conservatives – and in turn for them in combination with Reform – is actually three points lower among those who wish to stay out (56%) than it is among those who voted Leave (59%).

We will consider why the picture is much the same in the two halves of the table in a moment. But first we should pick up the fact that in both halves pro-EU voters are currently more willing to back one of the parties that once backed a second referendum than anti-EU voters are to support one of the pro-Brexit parties. This stands in contrast to the position in 2019, when (among the respondents to this poll) the 71% of 2016 Leave voters who backed a pro-Brexit Party was similar to the 73% of Remain voters whose party preference matched their attitude towards Brexit. As a result, although Remain voters still distribute their party preferences across a wide range of parties, the Conservatives’ popularity among Leave voters, which was crucial to their success in 2019, is now no greater than the level of backing that Labour receives among Remain supporters. The decline in the Conservatives’ popularity in recent months, not least in the wake of ‘partygate’, has served to undermine the foundations of the electoral coalition that delivered Boris Johnson an overall majority in 2019.

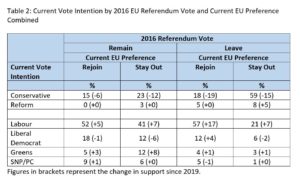

But to return to our main theme. The fact that someone’s current attitude towards EU membership is no more strongly linked to current party preference than is 2016 referendum vote suggests that perhaps those who have changed their attitude to EU membership in the interim may not have changed the party they support in tandem. Such a pattern would provide further evidence that the influence of Brexit on party choice is indeed on the wane. To examine whether this might be the case, in Table 2 we look at party preference by how people voted in 2016 and their current attitude towards EU membership in combination. Thus, in the case of 2016 Remain voters, we show the distribution of current party preference separately for those who would vote to rejoin and those who would now back staying out, while 2016 Leave voters are also divided in that way. Meanwhile, as well as showing the current level of support for each party, the table also shows (in brackets) how much support for that party has gone up or down since the respondents to Redfield & Wilton’s poll voted in 2019.

There are some clear differences of party preference between those Leave voters who would now vote to rejoin the EU and those who would stay out. Support for Labour is far higher among those Leave voters who would vote to rejoin (57%) than it is among those who would stay out (21%). Conversely, only 18% of those Leave voters who back rejoin are currently backing the Conservatives, compared with 59% of those who would stay out. That said, Leave voters who now support rejoin werealready more likely to vote Labour and less likely to back the Conservatives in 2019 – indeed Labour (40%) were slightly ahead of the Conservatives (37%) among this group. Perhaps some of these voters had already changed their minds about Brexit before 2019, and/or perhaps some have since brought their attitude to EU membership in line with how they voted in 2019. However, even when we take this pattern into account, support for pro-Brexit parties has fallen more among Leave voters who now back rejoining (19 points) than it has among those who would stay out (ten points). Conversely, support for one of the parties that once backed a second referendum has increased since 2019 by 21 points among 2016 Leave voters who are now rejoiners, but by only six points among those who wish to stay out. In short, it looks as though some 2016 Leave voters who would now prefer to rejoin the EU have since 2019 switched their party preference in tandem with their revised view on EU membership.

In contrast, among 2016 Remain voters the differences in party preference between rejoiners and those who wish stay out of the EU are modest. True, the level of Conservative support is a little higher among those who now wish to stay out (23%) than it is among those who wish to rejoin (15%), while Labour is a little more popular among rejoiners (52%) than it is among those who wish to stay out (41%). But these modest differences simply reflect differences in the way that the two groups voted in 2019. In fact, at twelve points, the fall in Conservative support since 2019 among those Remain voters who have switched in favour of being outside the EU is larger than the fall among those who would like to rejoin, the very opposite of what we would expect if voters were shifting their party preference in line with their revised views on EU membership.

There is then an important contrast between 2016 Leave and Remain voters in how their party preference has shifted since 2019. Leave voters who now feel that the UK should be part of the EU have been particularly likely to swing away from a pro-Brexit party choice, whereas those who backed Remain in 2016 but would now support staying out have not swung in favour of a pro-Brexit party. This contrast helps explain why, as Table 1 showed, those who currently support being outside the EU are three points less likely than those who voted Leave in 2016 to be supporting a pro-Brexit party. It is also a pattern that mirrors one we reported yesterday whereby those who voted Remain in 2016 but now wish to stay out of the EU largely still take a negative view of the consequences of being outside the EU – and thus further underlines the suggestion that this is a group whose attitude to being out of the EU looks more like an acceptance of a fait accompli than a Damascene conversion to Brexit.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.