Following the EU referendum, the UK witnessed a rise of Brexit identities as people aligned themselves with opposing sides in the Brexit debate. Many of the country’s citizens now saw themselves as Remainers or Leavers. These Brexit identities were often felt more strongly than party identities.

But what of these Brexit identities now? It has been more than five years since the referendum vote. While the process has been lengthy, a Brexit deal has now been achieved and the UK has left the EU. The likelihood of a second referendum and of the UK rejoining the EU in the near future have seemingly faded to near zero, with neither of the UK’s two biggest parties currently espousing either of these possibilities. Given these circumstances, it might be expected that people’s Brexit identities will have weakened, now that the public have moved on.

Using the NatCen Panel, we have collected data on Brexit identities at regular intervals since June 2018, thereby enabling us to see how they have evolved during the Brexit process and since.

Respondents were asked:

Thinking about Britain’s relationship with the European Union, do you think of yourself as a ‘Remainer’, a ‘Leaver’, or do you not think of yourself in that way?

If they did not respond ‘Remainer’ or ‘Leaver’ at that point, they were also asked:

Do you think of yourself as a little closer to one side or the other?

Prevalence

Contrary to what some may have expected, the Brexit identities of ‘Remainer’ and ‘Leaver’ are as prevalent today as they were three years ago. In our most recent survey, in August 2021, 78% said they were a Remainer or a Leaver in response to our first question. This proportion rose to 86% when those without a Brexit identity were asked if they were closer to one side or the other and added to the tally. This latter figure is only a little below the 89% recorded when we first asked about Brexit identity in June 2018, since then the proportion has proved remarkably stable.

Strength

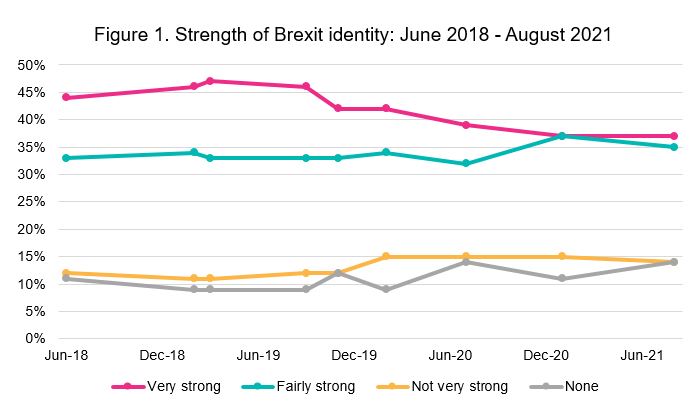

The NatCen Panel has also asked those who said they were a Remainer or Leaver whether that identity was ‘very strong’, ‘fairly strong’ or ‘not very strong’. While the proportion with a Brexit identity has remained stable, the reported strength of that identity has weakened somewhat over time. In June 2018, over four in ten (44%) had a very strong Brexit identity, and the figure stood at 46% throughout 2019, when Brexit was the subject of a parliamentary stalemate. However, shortly after the UK left the EU at the end of January 2020, the proportion with a very strong identity had slipped to 42%, while by January 2021, shortly after the UK had left the EU single market and customs union, it had fallen to 37% – though, as Figure 1 shows, it has remained at that level in our most recent survey.

It might be anticipated that this decline in the strength of Brexit identity has been more marked among Remainers, as they have come to accept that Brexit has been done. However, this is not the case. Rather, Remainers have always been somewhat more likely than Leavers to say that their identity was a very strong one. In our first survey, in June 2018, 53% of Remainers said their identity was very strong, compared with 45% of Leavers, Now, in our latest survey, while 47% of Remainers say their Brexit identity is very strong, only 37% of Leavers feel the same way. In short, the erosion in the strength of Brexit identity has been just as evident among Leavers as it has among Remainers.

Party Identity

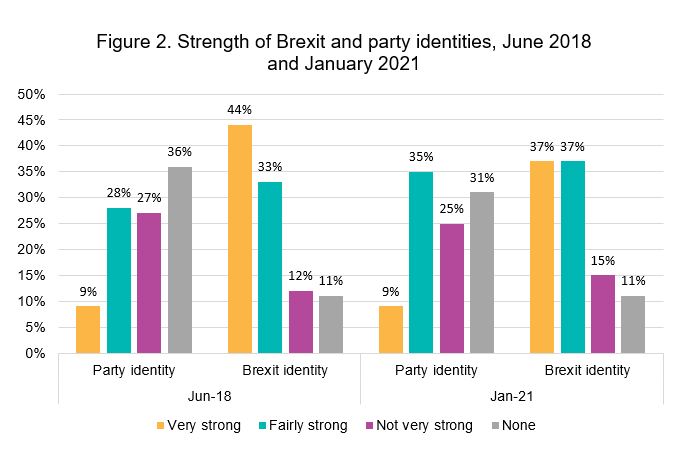

Meanwhile, although there has been some decline in the prevalence of strong Brexit identities, they are still far more commonplace than strong party identities. On the surveys we conducted in June 2018 and January 2021 we also ascertained the strength of people’s attachment to a political party, using a near identical question to that used to capture people’s Brexit identity. In both surveys, just 9% said they were a ‘very strong’ Conservative, Labour, etc. supporter, far short of the 37% who even now say they are a ‘very strong’ Remainer or Leaver (see Figure 2). Meanwhile, around one in three do not identify with any party at all, well above the 11% who do not have a Brexit identity.

Brexit and Party Identity

At the 2019 general election, over four in five voters backed parties whose stance on Brexit reflected their own view on the subject. Most Leavers backed the Conservatives, while most Remainers supported one of the opposition parties, most commonly Labour. But if Brexit identity now matters less, we might anticipate that the link between Brexit identity and party identity has weakened since the election.

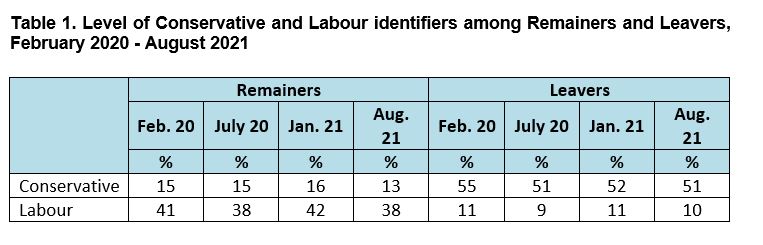

Table 1 shows the proportion of Remainers and Leavers who have said they identified with the Conservatives and Labour in each of the four surveys we have conducted since the election. It shows little sign of any diminution of the link between the two. Leavers are still five times more likely to say that they identify with the Conservatives than they are with Labour, while Remainers continue to be almost three times more likely to identify with Labour than the Conservatives. Two years on from the general election, the Brexit divide is as sharp as ever at least so far as the two parties’ core support of identifiers is concerned.

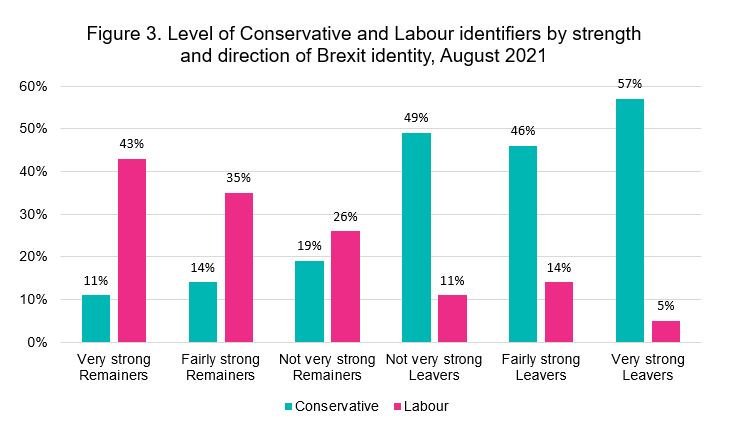

As we might anticipate, this divide is most marked among those with a very strong Brexit identity. This is especially the case among Remainers. As Figure 3 shows, while 43% of very strong Remainers identify with Labour, only 26% of not very strong Remainers do so. Conversely, whereas just 11% of very strong Remainers identify as Conservative, 19% of not very strong Remainers do so. Meanwhile, 57% of very strong Leavers identify as Conservative, compared with 49% of not very strong Leavers. In Labour’s case the figures are 5% and 11% respectively.

These patterns suggest that the link between Brexit and party identity could weaken somewhat should the decline in the strength of Brexit identity continue further. That said, even among not very strong Brexit identifiers the pattern of party identification among Leavers is still very different from that among Remainers. The strength – and indeed the prevalence – of Brexit identity will likely have to decline far more than it has done so far before it is likely to cease to shape the pattern of party identification.

Conclusion

Brexit has now been done, but Brexit identities are still widespread. True, they have weakened somewhat in strength over time, but they are typically still more strongly held than any party identity a voter may have. In addition, Brexit identity remains strongly associated with party identification. Politically, at least, Brexit still matters.

By Chujan Sivathasan

Chujan Sivathasan is a Research Assistant in the Longitudinal Surveys team at NatCen Social Research, working primarily on the NatCen Panel, with an interest in public opinion and political behaviour.

How anyone could believe that Britain leaving the EU was not beneficial escapes me. That organisation is a cold and heartless group of unelected presidents, who are not answerable to anyone. Britain had to leave the EU to allow their entrepreneurial and other abilities to flourish. Being dictated to by one of the many faceless presidents is not the British way. Thank goodness Britain had Boris to use his many talents to bring about Brexit. With all of the present upheavals underway Britain should ensure that Boris Johnston The Prime Minister continues to lead the country, but he must ensure that he and his colleagues ensure that bad habits that have developed since the election, must stop.

Finally Britain must completely break away from EU and get rid of the rules and regulations that have been loaded onto the British population.

Sincerely

Bill CoatesReport