As we noted shortly after the event, not only did the European election produce a dramatic result, but also it had an impact on voters’ preferences for Westminster. Both the Brexit Party and the Liberal Democrats enjoyed a substantial boost in their standing for a general election, the former gathering its support from those who voted Leave and the latter attracting the backing of those who voted Remain. The joint strength in the polls of the two parties that have traditionally dominated post-war British politics, the Conservatives and Labour, was as low as it has ever been.

However, given the experience of previous European elections, we could not be sure how long the boost in the fortunes of the smaller parties would last. Would it, like some previous post-European election surges, be a temporary development that would melt away in the heat of the summer sun – and the advent of a new Conservative Prime Minister, Boris Johnson? Or, did it reflect a fundamental shift in the party system that had been occasioned by the Brexit impasse and which, with Brexit still dominating the news, would likely be more permanent?

As MPs return to Westminster this week, the answers to these questions have become pressing. The stand-off over Brexit between the government and opposition MPs means there is much talk of an early election – either because Boris Johnson tries to precipitate one himself or because his government is brought down in a vote of no confidence. But to what extent and how is any immediate electoral contest likely to be shaped by the fall-out from the European election?

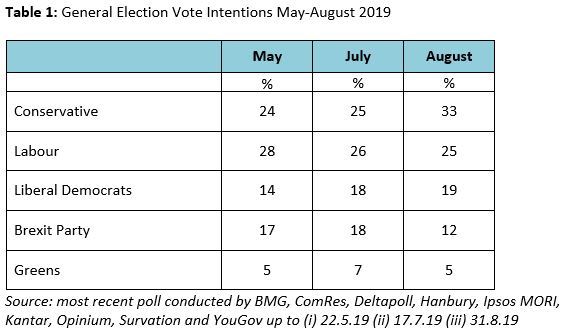

Table 1 summarises the trend in the level of support registered for the parties in the polls since the European election. The figures for May represent the position in polls conducted in the run up to European election day. The figures for July show the standing of the parties a couple of months later as the Conservative leadership election was drawing to a close. The equivalent figures for the end of August are shown in the final column.

Three key points emerge. First, the rise in Liberal Democrat support has proven to be highly durable. The party has remained on average at just below a fifth of the vote throughout the summer. As a result, the party is now in a stronger position in the polls than at any time since it entered into coalition with the Conservatives in 2010.

Second, the increase in Brexit Party support has proven less durable. Although the party maintained its level of support in the weeks immediately after the European election, it has fallen by six points since Boris Johnson became Prime Minister. Even so, that means the party’s standing is still more or less on a par with the 13% UKIP achieved in the 2015 general election.

Third, the beneficiaries of the fall in Brexit Party support have been the Conservatives, whose average level of support has risen by eight points during the last month or so. Whereas in the middle of July on average 26% of those who said they had voted Conservative in 2017 indicated that they would now vote for the Brexit Party, now the figure stands at just 16%.

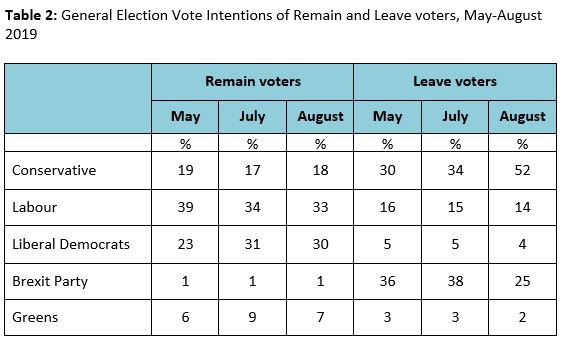

As a result, as Table 2 shows, whereas just a few weeks ago the Brexit Party was the single most popular party among Leave voters, now the Tories are ahead among this group by at least two to one. Indeed, the level of support for the Conservatives among those who voted Leave is almost back to the 55% level that the party was enjoying is mid-November last year, that is, at the point when Mrs May unveiled the draft Brexit agreement that she had negotiated with the EU.

In contrast, there is no sign of any revival in support for the Conservatives among those who voted Remain. At 18% the level of support for the party among this group is still much as it was during the course of the European Parliament election, and is still noticeably below the 26% level at which it stood in mid-November. As a result, whereas in mid-November for every Remain voter who was backing the Conservatives there were two who had voted Leave, now there are three Leave voters for every Remain voter within Conservative ranks. The fall and rise in Conservative support during the course of the Brexit impasse has left the party with an electoral base that is even more Eurosceptic than the coalition that was backing Mrs May.

Thus, on the Leave side of the Brexit divide much of the division in the level of party support that emerged in the wake of the European elections has been reversed, though the Brexit Party is still a more substantial force than UKIP were in advance of that ballot. (Support for Labour among Leave voters is, in contrast, some twelve points down on where it stood in mid-November.) The same, however, cannot be said of those who voted Remain. The revival in Liberal Democrat fortunes during the European election occurred wholly among Remain voters and, as Table 2 makes clear, that position has not changed. As a result, the party is still challenging the dominance of those on the Remain side of the Brexit debate that the Labour party once enjoyed. On average, almost one in five (19%) of those who voted Labour in 2017 are now saying that they would back the Liberal Democrats, a figure that has not changed significantly during the course of the last three months. It is, of course, the division of the Remain vote between Labour and the Liberal Democrats that creates the possibility that the Conservatives might be able to win an overall majority despite enjoying no more than a third of the popular vote.

So, the fallout from the European election has not proven to be a seven-day wonder. People’s views on Brexit still have a greater impact on their party preference for Westminster than hitherto. The Liberal Democrats, who have become a party that appeals almost exclusively to Remain voters, have retained their advance. Although the Brexit Party, whose appeal is confined to Leave voters, has lost some of the support it gained during the European contest, it still appeals – exclusively – to a substantial body of Leave voters. Meanwhile, in so far as some Leave voters have switched (back) to the Conservatives they have helped ensure that the Tory vote has become more decidedly Eurosceptic than before.

Clearly, Brexit continues to shape and reshape British politics – and it is a process that seems unlikely to end any time soon.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

the EU wants to take over our armed services no thank you check it out do you want to be a member of the 4th ReichReport

your choice, withhold the truth.Report

REMAINERS KEEP DENYING LEAVEING VOTE, BAD DEMOCRACY , ” LET RIGHT BE DONE” LEAVE. LABOUR STOP HIDING FROM A ELECTION, Report

I’d say that the events of the past 24 hours confirm that now all politics is Brexit. The Telegraph recently listed a couple of dozen times that Corbyn, or other senior members of the Labour Party recently called for an early GE, and yet today they would not vote for one when it was handed to them on a plate.

That says two things. One is that Corbyn realises that he has no chance in a GE that is framed as the People and Boris versus Parliament, and the second is that Corbyn knows that an early GE would clean out all of the “rebel” Conservative MPs he so often depends on to get “split” headlines. In other words, an early GE would finally put an end to Europe as an automatic “Tory civil war”. It would also result in the Conservatives having a much cleaner and more focused message on non-Brexit issues after the GE.

I think we are also seeing something about how misleading the “Westminster bubble” can be to MPs and Press who live inside it. Anti-Brexit MPs think they are incredibly clever to exploit Parliamentary rules to frustrate the expressed will of the voters, and the Press think they are incredibly clever to analyse and explain the exploitation in patronizing ways. But it all looks quite sordid from outside the bubble, and the next GE will sweep all the clever exploitation away, because a GE isn’t about arcane Parliamentary rules, but about one man one vote.Report

“People’s views on Brexit still have a greater impact on their party preference for Westminster than hitherto. ”

I think another way to put that is that a GE will be mostly a rerun of the 2016 referendum. That is important, because the rough rule for referendums in the UK is that we only have a nation-wide referendum – the Sottish and NI referendums were regional – when an important issue does not break down along party lines.

So, having failed to implement the result of the 2016 referendum, we now find that all politics fails to break along party lines, hence the coming GE as follow-up referendum.

The issue that has been the most important for the past three years isn’t cleanly represented by the usual political party system. I’d say that situation is set to continue, and that if the two main parties think they can go back to business as usual after this GE, they are kidding themselves. The one issue that exercises the voting public the most simply isn’t “political” in the usual sense. It’s an issue that cuts across politics, and will probably continue to do so.Report