There was a ready acceptance among politicians and commentators as the local election results gradually emerged on Thursday night and Friday morning that the outcome reflected voters’ views about Brexit. Not that they necessarily agreed as to what message the electorate were sending. Those of a Leave disposition interpreted the decline in both Conservative and Labour support as evidence that voters wanted the House of Commons to get on with delivering Brexit. Those of a Remain persuasion noted the increase in Liberal Democrat and Green support and suggested that the outcome represented an endorsement of the call that voters should decide the fate of Brexit in a second referendum. Of course, fitting the facts to match prior preconceptions has long become a familiar feature of the Brexit debate.

But what impact, if any, did Brexit have on the outcome of the local elections? In truth, discerning motivation from aggregate election results is always a potentially hazardous exercise. The ballots themselves tell us nothing about why people voted as they did. However, geography can provide us with some clues, especially if our proposition is one that implies that voters will have changed the party they support because of Brexit. If, for example, it is the case that Leave voters are disenchanted with the Conservatives’ failure to deliver Brexit and, as a result, were less willing to vote for the party in the local elections, we would anticipate that, other things being equal, the fall in Conservative support would be greater in those areas where more people voted Leave in 2016. Even then, it is not necessarily the case that such a pattern has been occasioned by the behaviour of Leave voters – it may be that Remain voters living in Leave areas were more likely to switch from the Conservatives than were Remain voters living in more pro-Remain areas – though such an explanation obviously seems less plausible. This, perhaps, is especially so given that there is plenty of contemporaneous polling evidence that Leave voters have been defecting from the Conservatives in large numbers.

Mind you, even this approach – looking at geography supplemented with evidence from opinion polls – has its limitations. What if both Remain and Leave voters have defected from a party in roughly equal proportions – as recent polls have suggested has been the position so far as Labour is concerned? Geographically, that should mean that there is little difference between Remain and Leave voting areas in the scale of that party’s losses. And maybe in turn that might mean that its loss of support has in fact nothing to do with Brexit. On the other hand, it could mean that the party’s stance on Brexit has led to a loss of support among both Remain and Leave supporters – perhaps because it backs a compromise that satisfies neither – and therefore has everything to do with Brexit. Distinguishing between these alternative interpretations might be thought near impossible – at least in the absence of polling information that might cast some further light on the issue.

To these considerations, one other has to be brought to bear – time. If we think that a party has lost ground among a body of voters we need to be clear ‘since when’ that is thought to have happened. In so far as we are interested in the impact of the ‘Brexit impasse’, that is, the failure of the House of Commons to progress the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, we should be examining how party support has changed since the EU withdrawal treaty was unveiled in mid-November. There were, of course, no local elections at that time. However, there are local elections in England every spring, and, as a result, it is in many places possible to compare the performances of the party this year with what happened last year. That is still not ideal, but it is potentially more informative than simply comparing the outcome this year with what happened four years ago, in 2015, when local elections were held on the same day as a general election (and enjoyed much higher turnout as a result), even though that happened to be the occasion on which most (though not all) of the seats up for grabs last week had previously been contested. A lot of Brexit and non-Brexit water has passed under many bridges during the last four years, thereby potentially muddying our understanding of the impact of the Brexit impasse. This observation proves to be particularly important in understanding the performance of the Conservative party.

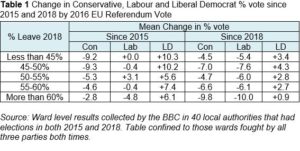

Given these observations, it should be apparent that the most straightforward way of trying to discern the impact of Brexit is to examine whether the change in a party’s share of the vote varied systematically between those areas that voted Remain and those that backed Leave. The following table is based on the detailed results in 720 wards located in 40 local authority areas as collected by the BBC. It shows the average change in the level of support for the three main parties in England since both 2015 and 2018, broken down by the level of support for Leave in 2016 in the council area in which the ward is located. Note that the table is also confined to those wards that each of Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats fought on both occasions – otherwise our figures might be distorted by changes in the pattern of candidature.

If, first of all, we focus on the left-hand-side of the table, on the changes in party support since 2015, we see some very clear patterns, albeit, perhaps, not always ones that we might have anticipated. In the case of the Liberal Democrats it seems quite clear that the party advanced more strongly in places where less than half voted Leave than in places where more than half did so. That would suggest the party’s anti-Brexit stance might have been successful in winning over Remain voters. Conversely, there is an indication that Labour might have performed worse in those places that voted most strongly to Leave, though beyond that there is little systematic difference. Here is a hint – though no more than that – that in the most pro-Brexit parts of the country Labour may have particularly lost ground among Leave voters.

However, the figures in the Conservative column do not support the claim that disenchanted Leave voters in particular have defected from the Conservative party in droves. The party appears to have lost ground more heavily in pro-Remain areas than in those that voted most heavily for Leave. If this means anything at all, it would seem to imply that Remain voters have defected from the Conservative party because they are unhappy that the party is pursuing Brexit at all.

But then, we already know that that is indeed what has happened previously. It was a feature of the 2017 general election. Equally, last year’s local elections witnessed a tendency for the party to perform better in Leave voting areas than in Remain supporting ones. So, in comparing the results in 2019 with those in 2015 we may simply be picking up a movement that occurred some time ago, well before the Brexit impasse came into view.

That this is the case becomes apparent if we compare the Conservative performance last Thursday with what happened twelve months ago (see the right-hand side of the table). Then we see a very different, if less dramatic pattern. The party performed worse in places with a strong Leave vote, while its vote tended to fall less in more pro-Remain areas, altough the pattern is not an entirely straightforward one. Here is some sign that during the last twelve months the party has particularly lost ground among more Leave–inclined England, thereby partially – but only partially – reversing a previous tendency for the party to advance more strongly in such areas since the EU referendum.

In Labour’s case the link in last year’s local elections between the change in the party’s share of the vote and the outcome of the EU referendum was much weaker than was evident in the performance of the Conservatives. Consequently, when we look at the change in its share of the vote since 2018, the pattern is not dissimilar to that we saw when we examined the change in support since 2015 – again the party looks as though it performed least well in the most pro-Leave parts of the country. It seems then that rather than simply expressing frustration with the Conservatives’ failure to deliver Brexit, voters in Leave-inclined England seem to have withdrawn support from both main parties. Here, it seems is some evidence to support the claim that both parties were being punished for the Brexit impasse, albeit, perhaps, more especially by those of a pro-Leave disposition rather than by voters in general.

That said, what the comparison with last year’s local elections also makes clear is that both the Conservatives and Labour have lost ground heavily in both pro-Remain and pro-Leave England. As we noted above, how far such a pattern is a consequence of voters’ reaction to how they have handled Brexit is impossible to tell for sure. What, however, we do know is that both parties have seen their average standing in the opinion polls fall since mid-November, the Conservatives by no less than 11 points and Labour by six. We can therefore say that the results of the local elections are consistent with (and help to confirm) other evidence that both parties have struggled to maintain their support during the course of the Brexit impasse – albeit with the additional twist that perhaps Labour have in fact fallen back just as much as the Conservatives.

But what of the rise in support for the Liberal Democrats? Does this still appear to have been stronger in Remain voting areas when measured across the last twelve months rather than the last four years? To a degree, yes, but the difference is not as sharp as that over the longer time period. As in the case of the Conservatives and Labour what stands out most of all is a relatively poor performance in the most strongly pro-Leave parts of England. Otherwise, however, it is difficult to argue that the results suggest that the Liberal Democrats’ advocacy of a second referendum has brought the party a particular boost in Remain-inclined England in recent months – much, indeed, as the opinion polls have been suggesting.

Much the same has to be said of the Greens, who registered their best local election performance for a decade. Across all the wards where the party stood this time it won an average of 12%, while its vote increased by five points on last year in those wards it fought in both 2018 and 2019. But that increase was just as high in the most pro-Leave areas as it was in the most pro-Remain ones. Most likely the party’s success had more to do with the recent debate about climate change than the party’s stance against Brexit.

Still, at this point, there might be thought to be a bit of a puzzle. If the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats were all performing less well in the most pro-Leave parts of England as compared with last year (and the Greens no better), then who was performing better?

Part of the answer, at least, is UKIP. The party only fought this year’s local elections on a limited scale, contesting just one in six of the seats. But where it did stand – which was disproportionately in places that voted heavily to Leave (and seemingly more so than last year) – the party’s vote was up markedly on the nadir to which it had fallen a year ago. In those wards that it fought both this year and last year the party’s vote was up by as much as eight points, a figure that rose to 13 points in the most strongly pro-Leave areas. This was enough to push the party’s average share of the vote across all the wards in which it stood this year up to 15%. Although this performance was still not as strong as in the local elections held in 2015 and 2016 (on both of which the party’s vote was down on average by four points), it represents clear evidence that the Brexit impasse has instigated a marked revival in support for a Eurosceptic party, even though that party is according to the polls now overshadowed by a newcomer, Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party. That gives every reason to anticipate that the challenge from that quarter will be greater in the Euro-elections when the new Eurosceptic party will be on the ballot.

Between them UKIP’s advance (missing though it was from the media headlines) and the especially poor performance by the Conservatives and Labour in the most pro-Leave parts of England as compared with last year represents the strongest evidence provided by the local elections that the Brexit impasse has had an impact on party support. It suggests that some more Leave-inclined voters at least did take the opportunity to express their dissatisfaction with how Brexit has been handled, and that this cost both main parties support – including in the Conservatives’ case some of the gains that the party had previously made among this group in the immediate wake of the referendum. In contrast, caution certainly needs to be exercised in assuming that the rise in Liberal Democrat and Green support represents a markedly greater willingness by Remain voters in particular to switch to a pro-second referendum party in the wake of the Brexit impasse. More difficult to discern, however, are the implications of perhaps the most dramatic feature of the elections, that is, the sharp drop in both Conservative and Labour support on last year irrespective of how an area voted in the referendum. It might represent a cri de coeur from voters about the state of the Brexit process – but whether these voters agree about what they want done about it might be another thing.

A shorter version of this blog is available on the ukandeu.ac.uk website.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

Let’s be honest. Different Lib Dems in different parts of the country put more or less emphasis on Brexit issue in these local elections in their campaigning depending on how they felt it was a priority in electoral terms compared to other issues, particularly local ones. One cannot, however, say that the electorate’s vote for the Lib Dems ward by ward was determined in each area purely on the battlefield ground which the local Lib Dems themselves prioritised.

Report

On the doorstep – for the Lib Dems – I found that people were just plain fed up with politicians generally, but were somewhat persuadable of the argument ‘But this is local!’). However, that argument could only be put if they opened their doors. (We won where I was canvassing, by the way, though I do not claim cause and effect!)Report

Professor Curtice deserves respect and regard for analysis and assessment driven by the evidence not emotion. Having carefully followed his career over the recent years he reflects the better aspects of our commentariat – fearless opinion backed up by sound data. If his take on what has occurred differs from partisan viewpoints, then so be it. Interesting both the LibDems (a major revival from a low base driven by an army of mobilised remain issue progressives and centrists) and the emerging Brexit Party have two similarities: clarity of position on the big issue and freshness of voter appeal. Too many traditional Tory or Labour voters seem to feel cheated by their tribe and opted to “unfollow”. Look to these two to dominate the European Poll for emotional, logical and organizational reasons. Report

You suggest that some of the data may imply that Remain voters have defected from the Conservative party because they are unhappy that the party is pursuing Brexit at all. Or, might it be, that they are unhappy with the Conservative party, given what the Government’s pursuit of Brexit has revealed about a good number of its MPs.Report

@John Torrance: “Always always always Curtice refuses to acknowledge any drift away from Brexit in the polls in spite of the fact that no polling lead has existed for Leave for two years, a trend he studiously and quite scrupulous;y ignores.”

Even a brief examination of this website shows that that statement is plainly incorrect. As this article from Sept 2018 proves:

https://www.whatukthinks.org/eu/has-there-been-any-kind-of-swing-between-remain-and-leave/

It’s pretty obvious that Leave is losing support, with some caveats (for example, in some polling voters who said they voted to Remain in 2016 has increased by 5%), but the question is to the scale of the swing.

This article is specfically about the local elections, we are all aware (inc. Curtice) of the recent “background” trends in national polling, and the caveats that need to applied to such polls:

https://www.whatukthinks.org/eu/opinion-polls/euref2-poll-of-polls/

Just as the Tories and Labour can’t state that the local election result provides evidence that we want a deal, it also can’t be argued that the swing to Remain is significant in the context of any possible confirmatory referendum.

@John Torrance: “Leaving aside the major Lib Dem revival (over a shorter or longer period during the Brexit mess-so what?)”

“So what?” – Important events that impact voters occur over time.

Voters didn’t know what form the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement would take until after the 2018 local elections, so a comparsion between the local elections in 2018 and 2019 possibily provides an indication of the support for the Liberal Democrats as a result of the deal and their call for a confirmatory referendum.

While the comparsion between 2015 and 2019 indicates the change in support since before the referendum took place, the referendum result, up until the recent local elections. It is differcult to prove conclusively to what extent the increase in Liberal Democrat support over four years is due to a general revival since they were heavily punished in the local and general elections in 2015 due to the coalition government; what level is due to their stance on Brexit; and what level is due to a Tory protest vote in the English shires, who wanted to register their dislike of the government’s stance on brexit from either a Remain or Leave perspective, but would not vote Labour or other minor parties (noting that Ukip stood in very few wards).

It would be interesting to analyse the historic trend in the councils where the Liberal Democrats gained support, to have some indication of the normal levels of Liberal Democrat support, pre 2010, weighting for the changed demographics over that same time period. In all the ten councils the Liberal Democrats won, all had the Tories in second place, which might indicate that in these councils at least, voter motivations were more than just an increased support for Remain.

@John Torrance: “he rushes to pick up a UKIP gain in ONLY wait for it a sixth of the seats.and then focuses on only a handful of targeted seat which even then leaves them well behind 2016”

One paragraph, almost at the end of the article isn’t a “rush”, but proportionate and needed information.

That Ukip only stood in one sixth of all wards, and that the Brexit Party weren’t standing at all (and within weeks of formation have gained support in the national polls), should be a concern, not a reason to believe that the Leave vote has somehow been decimated in comparsion to 2016.

And Leave voters do not just support Ukip and the Brexit Party, they support all parties, including the Green and Liberal Democrat parties.

Given the low turnout of the local elections and the tendancy for many Leave voters to not vote in local or general elections, we need to avoid becoming complacent. Just look at the polling showing a Remain lead before the 2016 referendum.

Whereas, the support for Remain in London and Scotland; larger support for Remain in the young who could not vote in 2016; etc… will obviously boost Remain support and turnout in the EU elections and any confirmatory referendum.

Although I’m not suggesting this example is in any way representative, it serves as a warning on turnout:

Brighton and Hove – Remain 68.6% in 2016:

2019 Local election turnout – 42% (86,584 papers)

2016 EU referendum turnout – 74% (146,675 votes)

Basildon – Leave 68.6% in 2016

2019 Local election turnout – 26% (31,876 issued papers, inc. rejected)

2016 EU referendum turnout – 73.8% (97,999 votes)

@John Torrance: “I am not a conspiracy guy, I like the mild mannered Prof but his slant for qute a while now does make me suspect he is Brexiter. Brexit after all has been very kind to him. No doubt he will rush to embrace Farage in the Europeans and I will be very interested to observe this.”

Curtice is a well respected and awarded political scientist. What are your qualifications?

He is using his skills and experience to provide us with information and to warn us against interpreations of polling and voting, for either side of the Brexit debate, that have no objective basis.

Your allegations that he is a Brexitter are unfounded, and further reinforce just how tribal Brexit has become in the country. I welcome his calm and reasoned analysis.

—-

At this stage we should be ensuring that the vote for Remain parties is maximised and that we all vote tactically, in the upcoming EU elections.

While they will not be FPTP, the system of PR we use (excluding Northern Ireland) – the D’hondt method – isn’t much better. It creates a de-facto threshold which penalises the smaller parties, epecially in the EU regions that return a low number of MEPs

The website https://www.remainvoter.com is providing EU Election projections based on the latest polling of EU voting intension.

It is worth keeping an eye on their website, alternatively you can sign-up for voting recommendations.

Report

Always always always Curtice refuses to acknowledge any drift away from Brexit in the polls in spite of the fact that no polling lead has existed for Leave for two years, a trend he studiously and quite scrupulous;y ignores. Leaving aside the major Lib Dem revival (over a shorter or longer period during the Brexit mess-so what?) he rushes to pick up a UKIP gain in ONLY wait for it a sixth of the seats.and then focuses on only a handful of targeted seat which even then leaves them well behind 2016. The media were perfectly right to ignore this but Curtice dwells on ti here to a point of suspicion. I am not a conspiracy guy, I like the mild mannered Prof but his slant for qute a while now does make me suspect he is Brexiter. Brexit after all has been very kind to him. No doubt he will rush to embrace Farage in the Europeans and I will be very interested to observe this.

Report