One of the persistent findings of the polling on attitudes towards Brexit – both before and since the referendum itself – has been that voters are more likely to think that Brexit will be bad for Britain’s economy than anticipate that it will be beneficial. However, there has also been some evidence that voters’ views on the economic consequences of Brexit depend on the time frame that they are invited to consider. Both YouGov and Ipsos MORI have reported evidence that on balance voters are rather more optimistic about the consequences of Brexit in the long-term than they are about what it might mean in the short-term.

But why might this be the case? Given that the country was more or less evenly divided between Remain and Leave supporters at the time of the referendum and continues to be so now, perhaps it is an indication that Leave voters in particular are of the view that, although there might be pain in the short-term, ultimately Brexit will prove economically beneficial. After all, those who advocate Brexit have long argued that it will present Britain with new opportunities that, if successfully grasped, will enable the country to prosper. If this suggestion proves to be correct, it would imply that polls and surveys that have only asked voters about the more immediate consequences of Brexit have missed a key part of the explanation as to why the Leave campaign was able to win the 2016 referendum.

There is, however, another possible explanation – that the pattern represents the triumph of hope over expectation. Perhaps Remain supporters who anticipate that Brexit will be damaging economically in the short-term reckon that, in the long-term at least, things might turn out OK after all. They reason that whatever losses occur in the short term may eventually be reversed. If this perspective is correct, the tendency in polling to focus on people’s perceptions of the short-term consequences of Brexit would seem justified, as it implies that is these perceptions that are more likely to be reflected in whether people back Remain or Leave.

The latest British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey provides a unique opportunity to assess whether and why voters take a different view of the short-term and long-term economic consequences of Brexit. Included on the survey is an extensive suite of questions on attitudes towards Brexit funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, the results of which are released today in a report published by the Foundation. Included among those questions are a set that ask people what they think the consequences of Brexit will be in ten years’ time, one of which asked whether ‘as a result of leaving the EU Britain’s economy will be better off in ten years’ time, worse off, or won’t it make much difference?’. At the same time, thanks to funding provided by the ESRC as part of its ‘The UK in a Changing Europe’ programme, respondents were also asked whether ‘as a result of leaving the EU, Britain’s economy will be better off, worse off, or won’t it make much difference?’, that is, without specifying a time frame. The results of this question were previously reported as part of the most recent annual British Social Attitudes report.

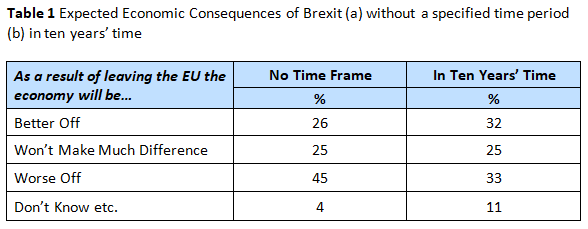

Comparison of the responses to the two questions reveals that they did obtain a rather different pattern of results (see Table 1). When respondents were not invited to consider a particular time horizon, they were nearly twenty points more likely to say they thought the economy would be worse off than to say it would be better off, a result that was not dissimilar to what was secured when the question was asked on the 2015 survey. In contrast, when people were asked what they thought the economic consequences of Brexit would be in ten years’ time, almost as many said that the economy will be better off as stated that it would be worse off. True, there may not be widespread optimism about the long-term economic consequences of Brexit, but, in contrast to the position when voters are not invited to focus on the long term, voters are at least not decidedly pessimistic about the prospects.

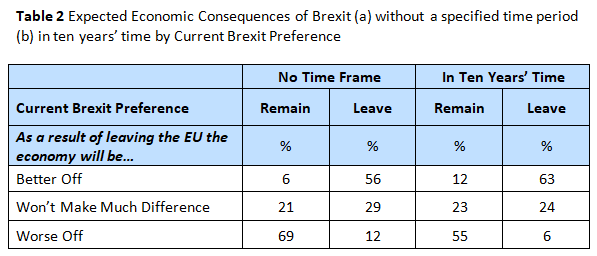

But is it Leave supporters or those who back Remain who are more optimistic about the long-term consequences of Brexit than they are about its more immediate implications? Table 2 reveals that Leave voters are somewhat more optimistic about the long-term. As many as 63% say that the economy will be better off in ten years’ time, compared with 56% who say it will be better off if no time frame is specified. However, at the same time Remain supporters are markedly less pessimistic about what Brexit will mean economically in the long term than they are when no time frame is specified. Whereas as many as 69% say that the economy will be worse off in the absence of a time frame, the figure falls to just 55% when asked to consider the position in ten years’ time. This shift of outlook among Remain supporters is more marked than the one we have identified among Leave supporters.

So, both of the possible reasons as to why voters are less pessimistic about the economic consequences are in evidence. Perhaps some of those who back Leave despite seemingly not being convinced that Brexit will be economically advantageous are indeed doing so because they anticipate that it will be beneficial in the long-term. However, it also seems that there is a not inconsiderable body of Remain supporters who are doubtful about the economic consequences of Brexit but are willing to accept – or hope – that maybe in the end things will be OK after all. As a result, attitudes towards the long-term economic consequences of Brexit are no more strongly linked to current Brexit preference than are attitudes to the more immediate consequences. But we will, of course, have to wait a long time before we find out whether voters’ relative optimism about the long-term economic consequences of Brexit proves to be justified.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

I have a wry smile when I read that remainers are short on definable and quantifiable engagement with issues. Right from the start of this whole debate the leavers side have never cared to actually come up with any answers to the many many quantifiable harms that leaving the EU will bring. On the contrary there has been a constant denigration of anyone who is an expert in their field bringing forward verifiable facts and figures as somehow part of project fear.

It’s a shame that people on your side of this debate do not understand why our relationship with the EU is more than a trading relationship. Already, even though we haven’t left yet, those forces who wish the dissolution of the EU and a return to the dark nationalisms of the past are emboldened and encouraged by what our country is doing. The world the brexiteers yearn for where individual European nations ‘take back control’ is shifting under their feet but they appear not to notice. A mythical future where huge economies like China and the US fall over themselves to come to the aid of plucky old global Britain or any of the other 27 EU members no longer exists, if it ever did.

Our arrogance and exceptionalism on the world stage for the past 2 centuries has not left us with many countries outside Europe who are willing to give us any favours. I remember the time before the Common Market when we were the sick man of Europe. We were able to use our membership to vastly improve our trading position and become a leading economy once more. We are trashing our own brand around the world, throwing away our soft power, losing the good will of our closest friends and expecting the US or China or India or the old commonwealth or some other parts of the world to pick us up in their tender embrace. It aint gonna happen.

Your figures about world trade and our prospective share of it are just wishful thinking, not definable and quantifiable certainties. You advocate throwing away a prosperous and peaceful present for some magical unicorn rainbow future which NO ONE can quantify or be certain about. I don’t know if your brow is higher or lower than mine but simplistic babble about WTO trading with the EU as any sort of future for the UK is just risible, non tariff barriers being at least as important as tariffs and not part of the WTO agreements. Can you seriously believe that any trade deal with Trump’s America could possibly to our advantage? We will be trussed up like a chlorinated chicken. God help us. No one else will.Report

My post was trying to make the point that our relationship with the EU is not solely, or even mainly, about trade. Your response is solely about trade. Which has reminded me of an important fact, which is that an obsession with trade and economics has eclipsed all other considerations in our national debate around the EU. However I feel I have to point out that since our trade with the rest of the world is greater than with the EU, it doesn’t mean we don’t need to worry if we trash it. A great deal of our trade is carried out under trade deals negotiated as part of the EU, which will not apply after we have left. We will be in the unfortunate position of having abandoned the largest trading block on our doorstep as well as many of the trade deals we previously had. In trying to renegotiate them we will soon find out that a potential domestic market of 60 million should does not carry the same clout as 500 million and our trading partners would be fools to offer the same terms as before. We will be at their mercy, on the doorstep, cap in hand, desperate for any kind of deal and may well find out that the Empire strikes back in ways the sunny polyannas of Brexit are totally unprepared for.

In addition the scientific and research base that underpins any successful economy is about to be decimated with no EU wide funded programmes forthcoming and the EU wide supply chains our exporters rely on to remain profitable being disrupted, we may well become more uncompetitive. And finally the growth rates in Europe, which is a relatively mature market, may be lower than other parts of the world but our growth rates languish at the bottom of the EU pile.Report

The reason that I talk about trade is that when peplle say that our relationship with the EU “is not solely, or even mainly, about trade” then I simply do not know exactly what they are talking about. This isn’t just you, or something recent. All through the Brexit debate I have noted that remainers stay away from issues that are definable and quantifiable, and prefer to talk about vague “atmospheric” issues that have no tight definition and no numbers, but which can be talked about in lyrical terms. Well, it’s a free World and if you say our membership of what was called the “Common Market” and which is still a “Single Market” and a “Customs Union” really isn’t about trade, then that is your privilege, but I think it’s what lost you the Referendum. That and cracks about “cap in hand” and similar low-brow journalistic cliches.

Secondly, you are repeating naccurate claims that were nailed as inaccurate over two years ago. We are not “abandoning” trade with the EU at all. At worst we will continue that trade with the EU under WTO terms, and in fact the EU itself has offered the UK a Canada-style free trade agreement that would mean no tariffs at all on most of our goods trade with the EU. The same goes for the rest of the World. The US, for example, our biggest single trading partner, is *already* preparing a free trade deal, and Australia has indicated the same thing. The rest of the World are not going to act as unpaid bully-boys for the EU. Why would thay? What would motivate them?

As Mr Moscovici helpfully informed the EU Parliament back in 2016 “This [data] means that in 2016 11% of the world GDP growth will come from the EU and 89% from non-EU countries, whereas in 2020 90% of the world GDP growth will come from outside the EU.”

At least Moscovici thinks trade is important, as does the EU Parliament, and if you think about it, he is telling them that trade with countries *outside* the EU is key to future EU growth.Report

It is myopic to look merely at anticipated economic benefits. Large swathes of leave voters were convinced by the ‘taking back control’ rhetoric and large numbers of remain voters wanted to keep all the advantages of the EU in terms of European citizenship, cooperation between states and sense of belonging to a continent wide family of nations, and no longer fighting wars every century.

The debate since the referendum has been couched almost entirely in terms of trade deals and their ability to Make Britain Great Again. The expected benefits of these deals cannot surely be as great as the expectations loaded on to them, although the public seem to be buying into this magical thinking.

No one really has certainty when long term economic forecasting is concerned and it’s a con to tell people there are definite outcomes to either leave or remain. The loss of the supra economic benefits of membership is a certainty, the amount of control our small nation will actually have in a world increasingly dominated by powerful states and corporations is not likely to increase.Report

There isn’t much concrete in your post, but it did remind me of an important fact, which is that in the past three decades, the EU share of UK trade and exports has fallen from a peak of 60% to around 45%, and PwC projects a further decline to 35% by 2030.

This should not surprise anyone, because the entire EU has slowed down significantly since its inception, from a Europe that enjoyed full employment, five percent annual growth and balanced budgets, to today’s one-two percent growth, nearly ten percent unemployment and high debt levels.

What has happened is that the fundamentals of the EU’s high wages and benefits work against them in a globalized world in ways that they did not when manufacturing was concentrated in the US and Europe. Unlike the UK, which has made a move into services and high-tech, the euro area is still struggling with the kind of manufacturing that China now does better.

The latest UK Government figures note that exports to the EU are at £274 billion while those to non-EU countries are £342 billion and exports to non-EU countries surpass those to the EU for the ninth year in a row, with, obviously a greater growth rate. Also, we run a widening trade deficit with the EU but an increasing trade surplus with the rest of the World.

Perhaps the real question to ask is: if we were already trading heavily with countries that were growing at 5-7% a year – and we are – would we be hammering at the gates to trade with an EU that grow by about 2% in a good year?Report

I can’t speak for anyone except myself, but the reason I expect the UK to be much better off in the medium to long run – five to fifteen years – is pretty simple.

It is that when an economic unit such as the UK has more freedom to react to events, then it does so, and it does well, but when it is constrained by a framework designed for the benefit of others, it cannot react so freely and so does badly.

One good example was the Bretton-Woods currency arrangement, under which the UK was obliged to use its currency reserves to keep the Pound exchange rate within a small margin vis a vis the Dollar. Since the UK ended the War with very high debt levels, inflation was used to erode the real value of debt, which led to UK inflation being relatively high, and the Pound being chronically weak against the Dollar, with periodic reserve crises and devaluations as a result.

Rather amazingly, we then repeated thhis failed experiment by joining the ERM – apparently in the belief that constrainst would be “good for us” and make the UK more like Germany – and the result was the same, a reserves crisis and a large devaluation. Once out of the ERM, the UK economy began its longest peacetime expansion.

I expect Brexit to have much the same results. Inside the EU our trade deals are handled by Brussels, whose top priority seems to be to preserve Germany’s giant trade surplus, which means that they primarily protect German manufacturing, and secondarily French, Spanish and Italian agriculture, none of which benefits the UK much. In fact, EU tariffs raise costs for UK consumers. Outside the EU I expect UK trade deals to be designed around the joint needs of the UK and its trade partners outside the EU, and not to be designed to protect Germany’s export trade.

In other words, the UK’s economy will perform as well as its workforce, skill and investment allow it to perform, which is almost certain to be better than those three minus trade regulations designed to benefit someone else.

The worst case would be to “leave” the EU but to keep the constraints of the Single market and Customs Union, but no-one could be that foolish, could they?Report