One of the intriguing and important questions about the fallout from the EU referendum is whether it will serve to reshape British party politics. Both UKIP (in the pro-Brexit camp) and the Liberal Democrats (in the anti-Brexit one) are making their very different perspectives on whether and how we should leave the EU the corner stone of their current appeals, as befits what were already the country’s most anti- and pro-EU parties respectively. In so doing they are competing for votes with two larger parties both of whom found their supporters badly divided in the referendum last June. We thus might wonder whether Conservative supporters who voted to Remain will stay loyal to a party that is now pursuing what many describe as a ‘hard’ Brexit. Perhaps they might be enticed to switch to the Liberal Democrats, who after all have traditionally been the party of protest for discontented Conservatives. Meanwhile, it has been widely suggested that Labour is at risk of losing many of its (working class) Leave supporters in the wake of an explicit appeal from UKIP for their support.

Regular readers will be aware that last week we questioned the apparent widespread belief, given much airing in anticipation of this week’s Stoke and Copeland by-elections, that most Labour voters in the North of England and the Midlands voted to Leave. We showed that, although they were more likely than their southern counterparts to have backed getting out of the EU, still no more than two in five of Labour voters in the North and the Midlands actually voted for Leave. Moreover, they were certainly far less likely to have voted that way than Conservative supporters in the North and the Midlands, of whom around two in three did so. Even when we take into account the fact that there are fewer Conservative than Labour voters in the North and the Midlands, these figures mean that a somewhat higher proportion of the Leave vote in the North and the Midlands came from Conservative rather than from Labour supporters.

That analysis in itself raised some questions about the viability of a UKIP strategy that is apparently focused on winning over Labour Leave supporters in the North and the Midlands. But, of course, the acid test of what impact, if any, the debate about Brexit is having on support for the political parties is to examine whether there is any evidence that those who voted for Remain or Leave have switched their party allegiance in one direction or the other since the EU referendum. That is what I have done in an article to appear in the latest edition of IPPR’s journal, Juncture. The analysis is based on polls conducted by YouGov – these are not only more numerous than those conducted by any other company but are also the only polls that have regularly reported separately the current vote intentions of Remain and Leave supporters.

Amongst voters as a whole there have been some clear movements since Theresa May became Prime Minister and her strategy for Brexit emerged. Labour support stood at 30% on average in nine polls conducted by YouGov in August and September last year, only a little below the 31% that the party won in the 2015 general election. In the seven polls that the company has conducted since the beginning of the year, that figure has fallen to just 25%.

Despite this decline in Labour support, UKIP have done little more than tread water. At 13%, their average level of support in YouGov’s polls to date this year is exactly the same as it was in August/September – and in the 2015 general election. Meanwhile the Conservatives have not done much better, edging up from 39% to 40%, enough to put them just a couple of points above the share of the vote won by the party in 2015.

The party that has made some discernible, if modest progress during the course of the Brexit debate is the Liberal Democrats. Last August and September the party was still running at just the 8% that it scored in 2015. This year it has been averaging 11%. The first signs of this turnaround began to emerge in the run-up to the Richmond by-election (held at the beginning of December), in which the party pulled off a notable victory. But it seems to have consolidated further since then.

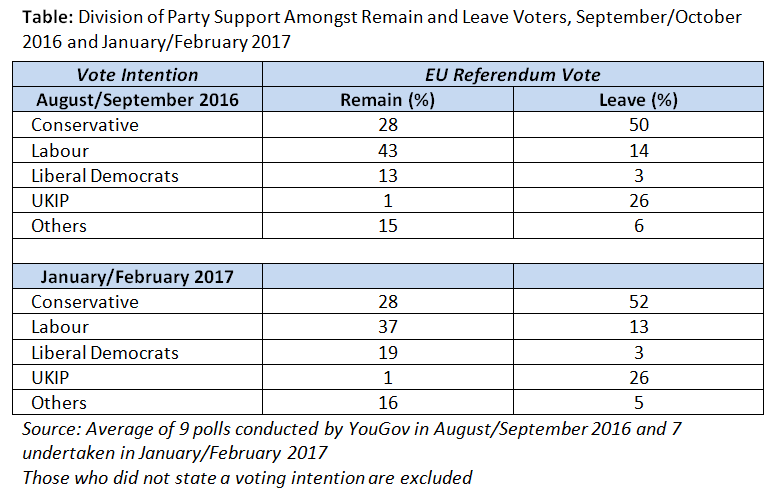

However, the fall in Labour support and the increase in the Liberal Democrats’ popularity have not occurred across the board. Both movements have been almost entirely confined to those who voted Remain last June. As the table below shows, Liberal Democrat support has increased from 13% to 19% amongst those who voted to Remain, while it has stagnated at a miniscule 3% amongst those who voted to Leave. Meanwhile, Labour support amongst those who voted Remain has fallen by no less than six points – from 43% to 37% – while it has dropped by just a single point (from 14% to 13%) amongst those who voted Leave.

There are two other features of the table that we should note. First, even in its currently enfeebled state, and even after losing ground amongst those who voted Remain, Labour is still the single most popular party amongst those who wanted to stay in the EU, and it remains nearly three times as popular amongst Remain voters than amongst Leave voters. Second, UKIP’s support is almost wholly confined to those who voted Leave, amongst whom the party is already well ahead of Labour. Between them these two patterns suggest that the potential for UKIP to increase its support further by winning over Labour voters is relatively limited. UKIP, it seems, are only capable of winning the support of those who voted Leave last June, and such voters are relatively thin on the ground in Labour’s ranks. In contrast, there are plenty of Remain supporters to whom the Liberal Democrats would seem to have at least some chance of appealing.

In voting in favour of the invocation of Article 50, Labour argued that it had to respect referendum result. That decision may, indeed, have helped shore up the support of the minority of its voters who voted to Leave. But, it may also have put at risk the loyalty of the much larger group of its voters who backed Remain. And in the battle to win over disenchanted Labour voters, it is the pro-Remain Liberal Democrats, not pro-Brexit UKIP, who have drawn first blood.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

Cameron did not give jo public enough info about what would happen if we left. If we had known all the facts we woul not be discussing Brexit.Report

If the Tory and UKIP vote had combined in Stoke, Labour would have lost the by-election.

If UKIP manages more effective campaigning and a scenario emerges with Tories and UKIP supporters tactically voting for each others’ parties in the GE (as happened in Copeland), isn’t Labour finished?Report

I don’t think that an electoral pact with the hated Tories would be popular with the working class. That would show too graphically what UKIP really are – a right wing split off from the ToriesReport

Conservatives have 28% support among Remain voters. Do you think those too are vulnerable as Tories have definitely embraced Brexit?Report

Doubt it. Tories who voted Remain did so largely out of loyalty to Cameron, or fear of change. The number of genuinely pro-European Tories, who may actually change their party support over Brexit, is vanishingly small.Report

Based on new members of the LibDems that I have met (and I’m an ex-tory one myself), you’re wrong. Rather than be ‘vanishingly small’ we appear to be satisfyingly large. I’ve not had one sensible response from a died-in-the-wool Tory to my question – “Why should a Tory voter who believes passionately in the EU ever vote Tory again?”Report

What Ken said. Plenty of ex-Tories saying hello in Lib Dem newbie groups, Witney and Richmond by elections, and many LD council gains coming from conservatives.Report