The public has become acutely aware of changes in immigration rates and attributes these changes to the UK’s membership of the European Union. This has been a direct consequence of the growth of immigration from the EU accession countries in Eastern and Central Europe. Inevitably, this process has important implications for the likelihood of a ‘leave’ vote in the forthcoming EU Referendum.

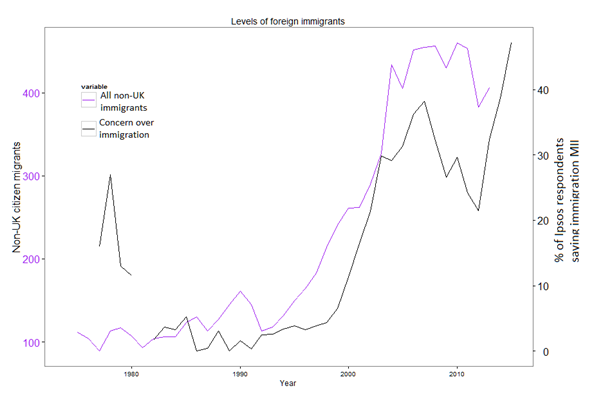

Actual immigration rates are the key to understanding levels of concern about immigration. Below (Figure 1) we show long-term immigration rates for non-UK citizens obtained from estimates of international migration provided by the International Passenger Survey. We also present (Figure 2 below) evidence on trends in concern about immigration expressed via responses to questions about what people think are the most important issues facing the country.

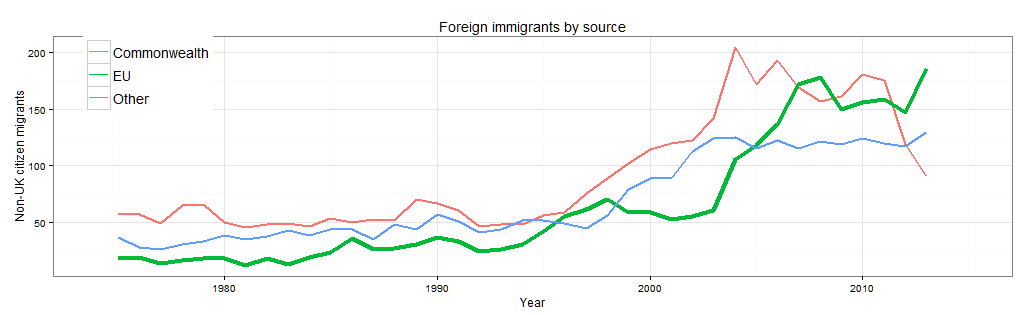

Figure 1 Number of Foreign Immigrants 1975-2014

Immigration increased markedly at the end of century and has remained exceptionally high since. We can see a spike in concern (Figure 2) in the 1970s when the National Front obtained some degree of political presence, even though there was no growth in immigration itself around that time. Far more noticeable, however, is the rise in concern that started just before the turn of the century. From this point on concern about immigration was closely associated with immigration levels. The dip following the onset of the economic crisis in 2007/8 is unsurprising given the impact of the crisis on levels of concern about the economy, but levels of concern began to increase once more after only a short interlude.

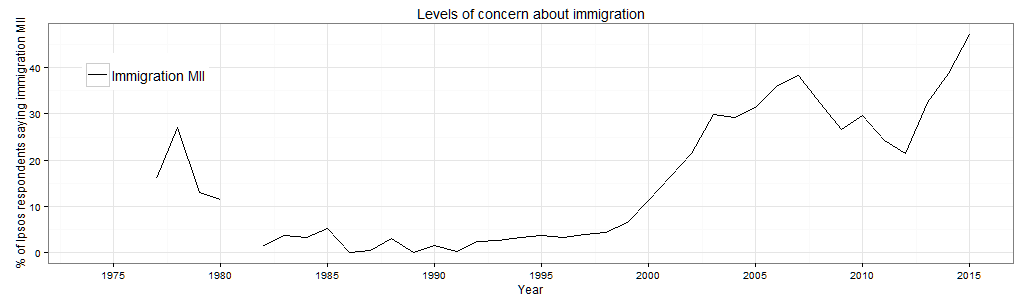

Figure 2 Percentage saying Immigration One of the Most Important Issues Facing the Country

Source: Ipsos MORI

The public thus appears to have become responsive to changes in immigration rates. However, overall rates of immigration do not themselves have implications for attitudes towards the EU. For immigration to have an impact on attitudes towards the EU people need to perceive an association between EU membership and levels of immigration. When we break down immigration into region of origin by separating Commonwealth, EU, and ‘other’ (see Figure 3) sources of immigration we can see that this is indeed what seems to have happened.

Figure 3 Foreign Immigrants By Source

EU immigration played no part in the rising immigration in the late 1990s and early 2000s – this was produced by an increase in asylum seekers from other parts of the world. EU immigration takes off with the 2004 accession of former communist-bloc countries of Eastern Europe into the EU and the Government’s decision not to restrict immigration from these countries during their first five years of EU membership. After 2004 EU immigration formed a major component of immigration into Britain. By 2013 it was the largest component.

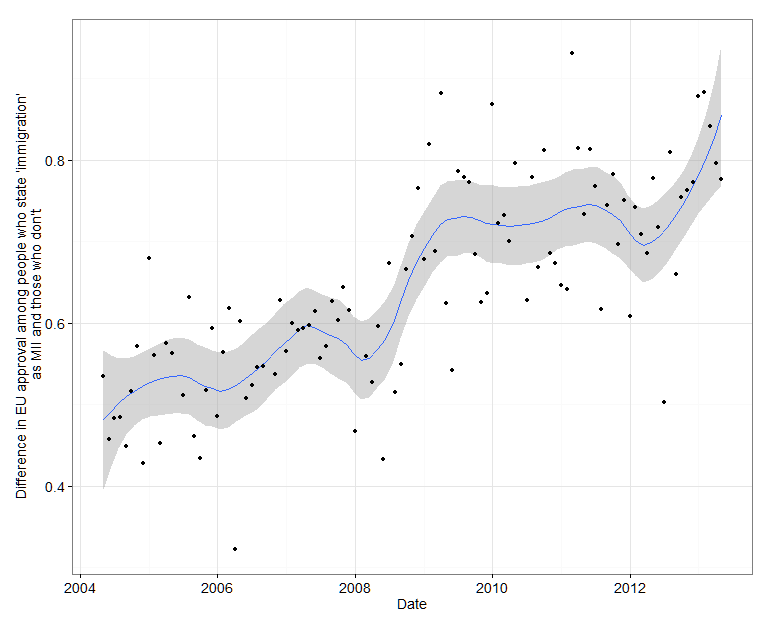

Did the public connect this change in the composition of immigration with their view of the EU? Recent rises in concern about immigration appear to be linked closely with trends in EU immigration and not with immigration from other sources: concern has increased along with increasing EU immigration rates even though levels of immigration from other sources are falling or flat. In itself, however, this aggregate relationship is not compelling evidence that individuals are linking their attitudes to immigration with those to the EU. Fortunately, we are able to look at this relationship more closely using the Continuous Monitoring Survey’s monthly readings, which contain measures of both concern about immigration and attitudes towards the EU for each respondent. We can therefore examine whether concern about immigration has become linked with opposition to the EU. Below (Figure 4) we show the difference in the pattern of response to the question, “How much do you approve of Britain’s membership of the EU?”, between those who believe immigration is one of the most important issues facing the country, and those who do not.

Figure 4 Difference in Level of Approval of the EU Between Those Who Say that Immigration is One of the Most Important Issues Facing the Country and Those Who Do Not

The difference between people who believe immigration is an important problem facing the country and those who do not in their level of approval of the EU widens sharply during the years following the accession in 2004 of countries from Central and Eastern Europe before flattening off during the economic crisis, only to rise steeply shortly afterwards as rates of immigration from the EU also shoot upwards.

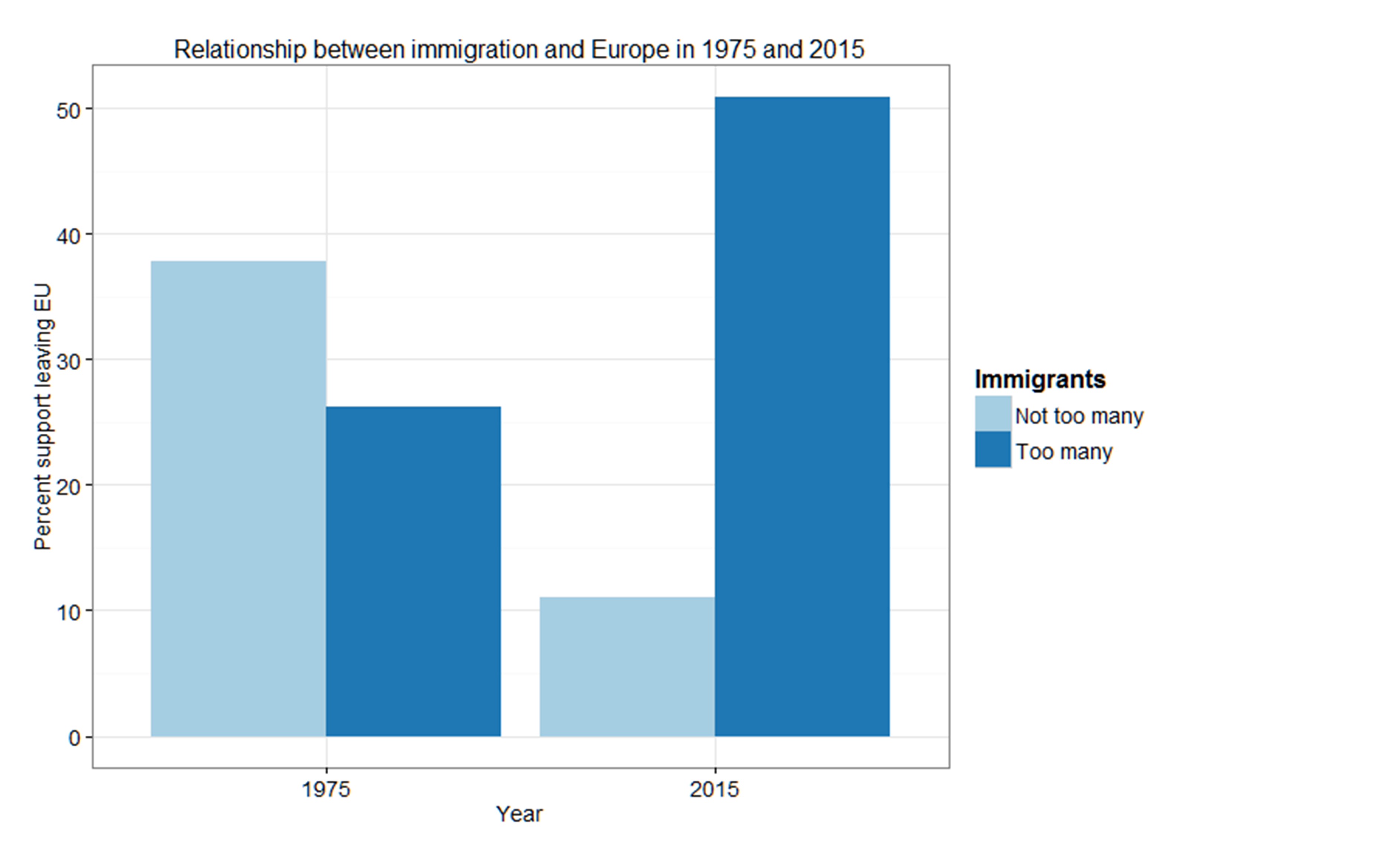

Clearly, the link between concern about immigration and a negative view of the EU has strengthened considerably in the years following the opening of access to immigrants from the 2004 accession countries. The relevance of this relationship for the forthcoming EU referendum is inescapable. Below we show the connection between believing that “too many immigrants have been let in to Britain” and support for leaving the EU. We also illustrate the significance of this relationship by comparing the position now with that at the time of 1975 referendum on EU membership (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Support for Leaving the EU by Perceptions of the Level of Immigration, 1975 and 2015

Source: British Election Studies funded by the Economic and Social Research Council

In 2015 only 10% of people who do not believe too many immigrants have been let into the country would vote to leave the EU. But no less than 50% of those who believe too many immigrants have been let in would do so. We might think that this reflects an inevitable relationship between anti-immigrant sentiment and a rejection of the EU, perhaps driven by a general distrust of foreigners or a fear of societal change. Yet in 1975 there was no significant relationship between immigration and support for leaving the EU. If anything, the relationship was the reverse.

The relationship between immigration attitudes and opposition to the EU has strengthened greatly in recent years, in direct response to the dramatic growth in immigration from, specifically, the 2004 EU accession countries. Recent immigration from Bulgaria and Romania is likewise accompanied by a markedly increasing level of concern about immigration. This spiral of alarm and negativity will clearly have an influence on the outcome of the EU referendum vote.

This post was co-authored by Jonathan Mellon, Research Fellow at Nuffield College, Oxford. It was first published on the UK in a Changing Europe website in collaboration with The Guardian

By Geoff Evans

Geoff Evans is Professor of Politics at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Nuffield College, Oxford

Depends where u live or lived what your thoughts are. Too many polish, Bulgarian and estonian immigrants where l live. They drive wages down, fill schools and housing. They get interpreters at dentist! Cant do with it carrying on like it is in Yorkshire Report

I am broadly favourable towards legal immigration. That said, I am struck by what this says about the EU’s inability to plan and to forecast the results of its legislation.

When the EU made free movement a central component of its Single Market, the Middle East existed, and had existed for quite some time. Italy and Greece had long and porous coastlines that are difficult to police, and that had also been the case for quite some time.

And yet the EU went forward with the principle of free movement, even though it did not have to. It could have left control of migration to member states and/or offered assistance to those with special circumstances to deal with, for example Italy, Greece and Malta.

It is a feature of the EU that it is quick to adopt measures because the principles behind them seem laudable, but the EU is much less good at predicting the practical effects of its measures.

To me, this says that staying in the EU is not, as some people say, the “status quo”. The EU will continue to introduce new measures without due attention to their side-effects, and member states will be left to clean up the resulting messes.Report

Cameron’s negotiations are producing little more than half hearted promises. Those EU states subsidised by Great Britain will try and stall the whole thing in the hope that the issue will drift away. As public opinion moves towards BREXIT Cameron will promise more but will fewer and fewer people feel inclined to believe himReport

Lets face it, David Cameron may have good intentions regarding the renogotiation of the UK’s membership of the eu! But he will not get very much at all from this organisation.

The 4 year deal regarding benefits is a non starter, although a good idea, but we will not get it, the UK needs to leave this corrupt organisation once and for all, and start again with a new reationship with the remaining EU, in a trading block, and some sort of single market regarding the free flow of goods and money, but not people!

The free flo of people may have worked out a few years back before the central and east europeans joined this organisation, this together with the current supposedly refugee crisis and the fact that the UK border agency probably really dont know how many people are in the UK, is totally unacceptable! And its high time we had control of all this given back to London!

There is an old saying that there is “never 100% security….but you try your best to make it happen!” Without the right to control immigration you do not have or ever will have security!Report

There is increasing discontent over immigration here in Germany. Many EU countries, like Greece, are already on the verge of collapse, including Italy and France as well as Spain and Portugal. Who is going to bail out these countries? Germany is the only one that is in a position to do this. Other countries such as Turkey and other eastern countries want to join the EU but their governments are not reliable. Do the British really want to stay in a group of bankrupt, incompetent and often corrupt countries?

The EU itself is also not free of incompetence and corruption among its leaders who were never voted into their jobs but appointed by their political friends. These are reasons why the curves in the above illustrations are going steadily upward.Report

I see “This spiral of alarm and negativity” as wholly positive.Report