Mrs May has seemingly called the election on 8 June in order to attempt to secure a mandate for her vision of Brexit. She anticipates that if she has a significantly larger majority in the House of Commons than she enjoys now her hand will be strengthened in the forthcoming negotiations with the EU. Whether that means she anticipates she will be better able to deliver the vision of Brexit she first laid out in her Lancaster House speech in January or, in fact, to strike a compromise that upsets some of her parliamentary colleagues is perhaps a moot point, but there is little doubt that in the Prime Minister’s view this is above all a Brexit election.

But that, of course, does not guarantee that this is how voters will regard the ballot. After all, attitudes towards Europe have long crossed party lines, albeit somewhat less so more recently. Indeed, in the EU referendum around three in five Tory supporters voted Leave while the other two-fifths backed Remain. At the same time, Labour’s ranks divided two-thirds Remain, one-third Leave. There would thus seem to be no guarantee that how people vote this time around will reflect their views about the desirability and shape of Brexit.

On the other hand, given the prominence that the debate about Brexit has had ever since last year’s referendum, perhaps at this election voters’ views on the subject will be reflected more sharply in their party choice, with the implication, perhaps, that some voters might vote differently at this election than they might otherwise have done.

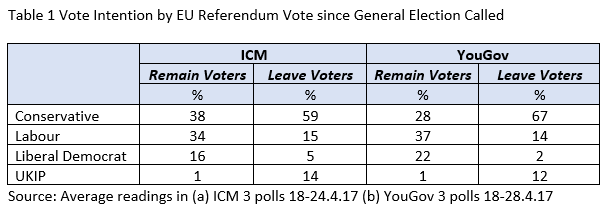

The most immediate way of identifying the extent to which attitudes towards Brexit are likely to be reflected in party choice is to compare the vote intentions of those who voted Remain last June with the intentions of those who voted Leave. The following table shows the voting preferences of these two groups according to the two companies, ICM and YouGov, that have polled most regularly since the general election was called and who regularly breakdown their numbers by how people voted in the EU referendum.

There are clear differences between Remain and Leave voters. Somewhere between three-fifths and two-thirds of Leave supporters now say they are going to vote Conservative. It is their support that provides the foundation for the Tories’ large lead in the polls. Remain voters, in contrast, are much less united in their preferences, with the Conservatives and Labour relatively evenly matched amongst them and with the Liberal Democrats also performing relatively strongly amongst this group. Although ICM and YouGov disagree somewhat about just how closely people’s vote intentions match their vote in the EU referendum, with ICM painting a rather less polarised picture, it seems we can safely conclude that (a) Leave and Remain voters currently intend to vote very differently from each other, and that (b) while the Remain vote is scattered across a number of parties, the Leave vote is primarily in the Conservative camp.

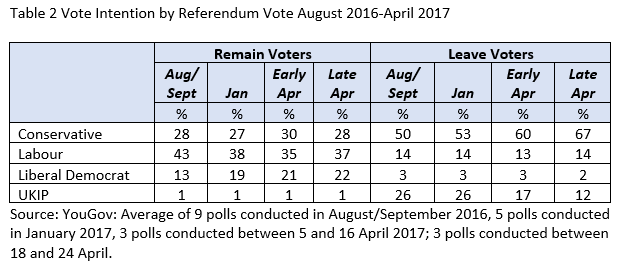

But is this any different from what we might have anticipated a year ago when the country voted narrowly to Leave the EU and David Cameron was succeeded as Prime Minister by Theresa May? To address this question, we show in Table 2 how the voting preferences of Remain and Leave voters have evolved since last year’s referendum. The data come from YouGov, who are the only company to have provided the necessary breakdown on a regular basis since last summer.

One key trend emerges. In the weeks immediately after Theresa May became Prime Minister, only a half of those who voted Leave said that they would vote Conservative. But that figure has climbed steadily to reach the two-thirds figure that we have already noted is to be found in YouGov’s most recent polls. Indeed, we can see that there has been as much as a seven-point increase in support for the Conservatives amongst Leave voters since the election was called. All of this increase, both before and since the election announcement, has come at the expense of UKIP, whose supporters seem increasingly to have come to the conclusion that their vision of Brexit is more likely to be realised by voting for the Conservatives rather than remaining loyal to UKIP.

In contrast, support for the Conservatives amongst Remain voters is much the same now as it was last summer. Here, the only notable shift has been between Labour and the Liberal Democrats, with the latter having made some progress amongst Remain supporters and doing so primarily at the former’s expense, a development I first identified in an article in IPPR’s house magazine, Juncture, earlier this year. The consequence, of course, is that while the Leave vote has become more concentrated within the ranks of one party, the Remain vote has become yet more fragmented. Little wonder, then, that some opponents of Brexit are trying to encourage tactical voting in constituencies where Labour and the Liberal Democrats are competing locally with an allegedly hard Brexit Conservative candidate.

That though still leaves us with the question: why have so many Remain voters remained loyal to the Conservatives? One possible clue at least was contained in a recent ICM poll which asked voters which of four options they thought would represent the best Brexit policy: leaving the EU no matter what, leaving the EU so long as the outcome of the negotiations are satisfactory, only leaving the EU if a second referendum approves the decision to do so, and not leaving the EU under any circumstances. No less than two-thirds of those who voted Conservative in 2015 and for Remain in 2016 picked one of the first two options; in contrast only around two-fifths of those who voted Labour and Remain did so. In short, it looks as though many a Conservative who voted Remain did so without a great deal of enthusiasm, and thus have been able to accommodate themselves to the prospect that the UK is now set to leave.

During the last forty years, the Conservative party has been on a long journey from the party that took Britain into the then Common Market to being the principal home for Eurosceptics. It looks as though this election could well mark the culmination of that journey – and thus justify the description of the contest on June 8 as being Britain’s Brexit election.

By John Curtice

John Curtice is Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and at 'UK in a Changing Europe', Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University, and Chief Commentator on the What UK Thinks: EU website.

I know you do this for a job but thank you for this non-partisan and informational column.Report

Good column. The way I see this is that post June 2016 people could still have different opinions about Brexit, but having voted to leave, your opinion about which party can deliver Brexit becomes more important. Which Brexit we get affects you, no matter how you voted.

To me, the Conservative line on Brexit just seems to have more clarity and certainty about it. The Conservatives seem to me to be about getting on with the negotiations, whereas the Labour position seems a bit vague and diffuse. Part of the time Labour talk as if they are still campaigning to Remain nearly a year after the vote, and part of the time they are talking about additional votes in 2019, even though, the way A50 is written, the exit deal is pretty much a take it or leave it issue. Report

Looking like Brexit in the bag and Labour condemned to lose many seats as a result of their failure to oppose the Govt satisfactorily.

If Corbyn refuses to resign after the election then surely we must have a split in the Labour Party, leaving Corbyn & his Momentum apparatchiks to wither in the vineReport

The UK is en route to a de facto one-party state

Report

I have voted in every GE since 1970 and on 8 June will be voting Conservative for the first time as the only means of defending the Referendum result and the integrity of our democracy. Yes, we are all Tories now.Report

1. If May does as well as the polls suggest then it should be easier for her to make concessions to EU27 because she will not have to worry about appeasing the 30+ group of die-hard MPs such as Peter Bone to obtain a majority in Parliament.

2.She might also feel emboldened to sack David Davis, who reportedly upset her at the recent infamous dinner with Juncker.

3. She will probably keep Boris inside the tent because he might be needed later on to say he has changed his mind, rehearsing that his decision to leave or remain was known to have been a close call.Report